Kerouac, caffeinated:

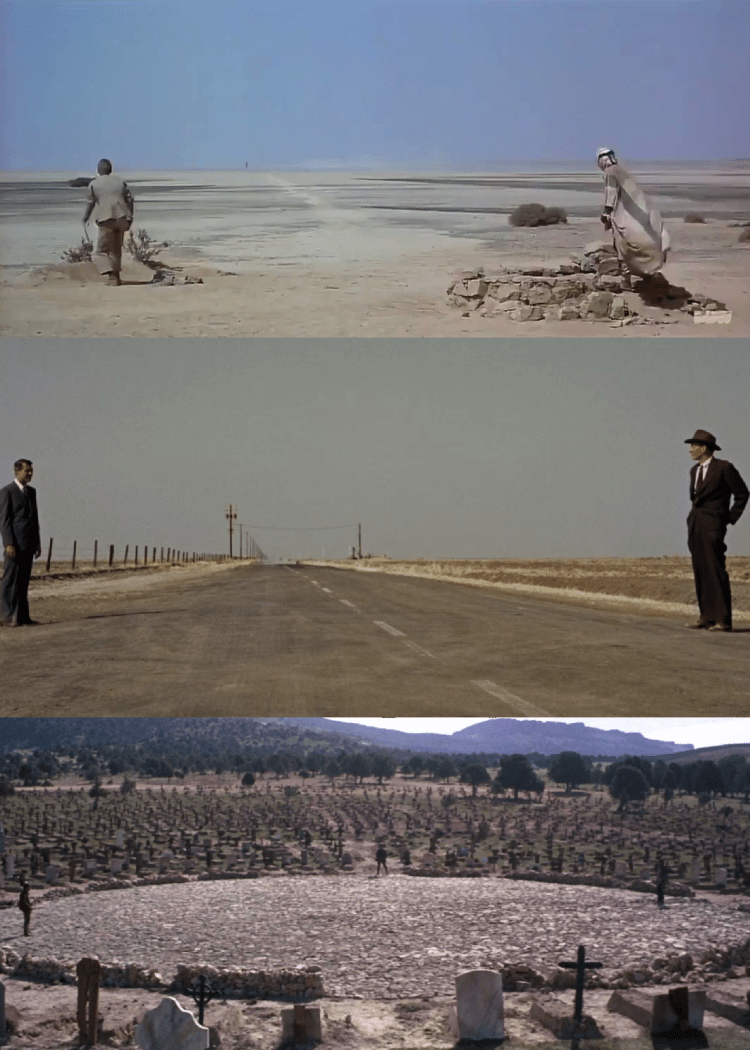

I told Dean [= Neal Cassady] that when I was a kid and rode in cars I used to imagine I held a big scythe in my hand and cut down all the trees and posts and even sliced every hill that zoomed past the window. “Yes! Yes!” yelled Dean. “I used to do it too only different scythe – tell you why. Driving across the West with the long stretches my scythe had to be immeasurably longer and it had to curve over distant mountains, slicing off their tops, and reach another level to get at further mountains and at the same time clip off every post along the road, regular throbbing poles. …” (On the Road)

Kerouac, amphetaminated:

We were talking about the Great Scythes of our childhood, when I, riding in New England littleroads with boulders and posts and hills of vine all along, would, imaginary, cut it all down with my scythe as my father swept the car by; and he, Cody [= Neal Cassady], in the tragic red roads of Sunday afternoon in Eastern Colorado, when blackhatted men grimly drive the children, swept alongside the car either on foot or wielding from inside the car a gigantically and intricately built Scythe that not only snipped the close posts and sage or wheat but extended itself in a monstrous dream to horizon with all the massiveness of unbelievable realities like the Oakland Bay Bridge or the skeletal Swiftian frame of the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia when they were raising the octagonal facewalls into place by longnecked celestial giraffe cranes, slow as the Bird of Paradisical Eternity raising the Great World Snake in its beak to the lost up, a scythe also so fantastic in its hinges that it could sweep over the flat plain, adjust itself to cut tablelands, rise a notch in the beyond and extend to horizons to cut mountain ranges entire while still managing in the little forefront blade to cut that bunchgrass into clouds of flying – We talked about this. (Visions of Cody)