Veterans Day at Peddie

Peddie is a well-known elite prep school in New Jersey, located in Hightstown, a small town just east of Princeton. According to Niche, it’s ranked #2 out of 126 in a listing of the Best Private High Schools in New Jersey, and #2 of 112 of the Best College Prep Private Schools in New Jersey. It also ranks first out of 139 of the Most Diverse Private High Schools in New Jersey. I’m at least vaguely familiar with the place, having been there a few times, having interviewed Peddie students applying for admissions to Princeton, and having grown up myself (for better or worse) in the elite Jersey prep school milieu. In short, within its rarefied circles, Peddie is a trend-setter.

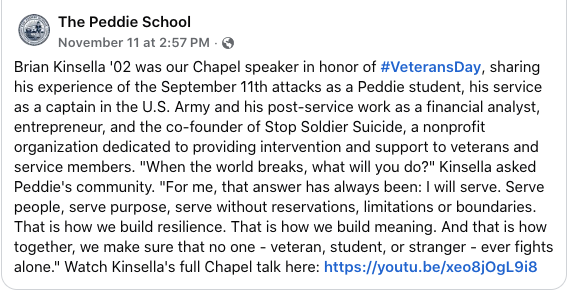

Like many schools, Peddie commemorated Veterans Day the other day. It did so by inviting a Peddie alum, Brian Kinsella, who, upon graduation, went into Army ROTC at Johns Hopkins, then went on to serve as a captain in the U.S. Army in Iraq after 9/11, and later co-founded a group called Stop Soldier Suicide. Here is Peddie’s social media blurb on the event. (This link takes you to a YouTube video of the talk, which is about 13 minutes long.)

Like Princeton’s event (described here a few days ago), Peddie’s took place in the school’s chapel. At Peddie as at Princeton, war is something to be sanctified and kept holy.

According to Kinsella, the problem we all face as Americans is that military veterans who fought for the United States have come home to an invisible enemy–themselves. Many of them, in despair or for lack of support, are committing suicide. We must therefore do what we can to support them and reduce the rate of suicide.

Kinsella invokes 9/11 as the reason why he joined the military. At no point, decades after the fact, does he ask why, or in relation to what, the 9/11 attack happened. It doesn’t matter to him why it happened. It’s simply an unquestioned axiom that it happened to us, so that any response to it was by definition an imperative of self-defense. The United States is by definition innocent; by definition–or self-definition–nothing it did could possibly have provoked so terrible an attack.

Brian Kinsella with Gen Mark Milley, photo credit: Sgt. Dana M. Clarke, Wikipedia

Even if we set that issue aside, Kinsella makes no attempt to explain the incongruity of his having been deployed to Baghdad after 9/11, as he was. What did Baghdad have to do with 9/11? What was he doing there? What was the Army doing there? None of that matters, either. Baghdad is where he was sent, so Baghdad is where he went. He doesn’t mention the abject, systematic lies by which the United States got into Iraq and stayed there as long as it did. “Politics,” he tells us with a straight face, is irrelevant, and not worth discussing in this context. What matters is the unity that the war achieved for Americans, regardless of its merits.

Naturally, he makes no mention of the millions of non-Americans killed in our “Global War Against Terror.” Where American unity is at issue, non-Americans lives become irrelevant. How many of those killed were innocent, and how many guilty–and if guilty, guilty of what? None of that matters, either. If we killed them, the assumption seems to be, they can’t have been innocent; if they were somehow innocent, we can’t have been at fault.

In other words, this is, like so many American discussions of warfare, a talk that’s begun in medias res. For all that Kinsella says in the speech about “service,” it doesn’t seem to occur to him how much of his adult life has been put to the literal service of unreflective dogmas and unquestioned commands. Oddly enough, at no point does it occur to him to mention that both of the wars in which he saw combat were wars in which the United States was soundly defeated. Recognition of those facts, however painful and obvious, would be off-script here. Americans are, after all, a famously “can-do” people. Faced with defeat, they do what they can do in response: they pretend that it didn’t happen. But if victory is the aim of warfare–as the war-hawks never tire of telling us–it surely matters when we spend decades on a war or two or three, and get defeated every time. And that we are is surely relevant to explaining a different kind of defeat, namely suicide.

9/11 Memorial, Lower Manhattan

Kinsella tells us, remarkably, that more American soldiers have died by suicide than have died at the hands of enemies in combat. I don’t know if it’s true, but whether true or not, the contrast at the heart of that claim strikes me as dubious. What exactly is the difference between being killed on the battlefield, and being sufficiently demoralized by the battlefield as to go back and kill yourself? Kinsella mentions “asymmetric” problem solving, as though it was exclusively the province of the US Army. He seems to have forgetten–or decided to forget–that his battlefield adversaries engaged in asymmetric warfare against his forces, that they won both wars by this expedient, and that the problem of soldier suicide could well be yet another of their victories.

Nowhere in Peddie’s PR, or in Kinsella’s talk, is a different framing of the supposed problem discussed, or the most obvious remedy for soldier suicide mentioned. Instead of framing the issue by a downstream problem, like soldier suicide, we might frame it in more fundamental terms: the United States’ addiction to warfare. From the country’s very founding, successive governments of the United States have seen the world as little more than a gigantic battlefield, where perceived threats to America’s perceived interests are to be resolved by killing and subjugating its perceived enemies.

Put this way, much of the military enterprise of the United States seems irrational and unjust. And put that way, we get a ready explanation for the preponderance of suicides among its troops. The view of the world on which it rests is fundamentally psychopathic. No one can sustain such a view of the world for long without going crazy and wanting to kill themselves. Or rather, no one can sustain it insofar as they allow themselves to grasp the relevant facts and hold them firmly in mind. Kinsella describes the soldier suicides as “collapsing under their own invisible weight.” It seems to me more plausible to say that they collapsed under the weight of unresolved contradictions–contradictions left both unaddressed and unresolved by his speech. It certainly would be a contradiction to send people to initiate acts of aggression in the name of self-defense. At no point does it occur to Kinsella that that’s exactly what his war, the war in Iraq, was.

9/11 Memorial, Eagle Rock Reservation, West Orange, New Jersey

Kinsella tells his audience that he characteristically works a hundred-hour workweek, part of it spent on his job as a financial analyst and partly as director of the non-profit. Consider an alternative set of uses for this time–three remedies for the soldier-suicide problem, all formulated to address the root cause of the problem, the addiction to warfare itself.

One way to solve the American warfare problem would be to put a moratorium in place on further warfare, including proxy warfare. Instead of plunging headlong into places like Ukraine, Palestine, Yemen, Lebanon, Iran, Venezuela, and Colombia–not to mention Haiti, Korea, Vietnam, Cuba, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Angola, Iraq and Libya–it might be wise to stop and take a breather. If we can experiment so promiscuously with war, we can do the same with peace. It’s hard to believe that the risks of restraint are higher than the risks of frantic action.

Another way to solve the same problem is to do a fundamental re-thinking of when war is justified and when it isn’t. When are we obliged to go to war? When are we obliged not to? How do we conceptualize the issues? How do we apply the relevant principles? I can’t think of a single war in the last eighty years in which any of these questions was asked or answered in any straightforward way. We simply went to war without knowing why we were, or why anyone should. Kinsella’s own speech illustrates the pattern.

A third way of solving our problem is to stop recruiting people into the military until we figure out why we need so large a military, assuming we do. It could be that we don’t. Figuring that out will go a long way toward reducing not only soldier suicide, but all of the other far more destructive effects of America’s imperial role in the world.

All of this seems to me a painful belaboring of the obvious. But what’s striking about the Peddie event is that none of it came up, even by implication. A supposed expert on warfare is brought before young people to impart his wisdom on his topic of expertise. Instead of raising any fundamental issues about warfare, or about the sad history of American warfare, or the sad state of imperialist militarism as such, he invokes his personal record of military valor to indoctrinate his audience into a partisan view of the American military with respect to a narrow and derivative issue.

Revolutionary War Monument Commemorating the Battle of Springfield, South Mountain Reservation, South Orange, New Jersey

Revolutionary War Monument Commemorating the Battle of Springfield, South Mountain Reservation, South Orange, New Jersey

And indoctrination is the right word here: students are left believing that virtue consists in taking all of the most fundamental questions for granted, and then left with the expectation that they’re to valorize the heroes of the U.S. military, feel empathy for them, and strain every nerve to prevent the next war hero from committing suicide. With that thought drummed into their heads, there’s no room for second-guessing the justifiability of the wars that make it all necessary. What matters, Kinsella reminds us, is “belonging.” We belong to America, and it to us. If you’re outside of the circle of belonging you are either morally irrelevant, or else marked for death by those who do belong. Kinsella is not wrong in thinking that the prep school ethos of belonging preps you for warfare. An army is just a prep school clique with guns.

Every word of Kinsella’s speech is imperialist propaganda, but–as has been the case with imperialist propaganda for thousands of years–couched in such a way as to make warfare sound like a gigantic charity event. Kinsella is in good (meaning horrific) company here. From a rhetorical perspective, his speech follows an age-old script. The Greeks gave a version of it, as did the Macedonians. The Romans gave a version, as did the Crusaders. The Spanish gave a version, as did the Portugese, French, British, Belgians, Italians, and Germans. Now the Americans are giving their version. The result is always the same: soldiers fall dutifully into line, as they have for thousands of years, then fall dutifully into their graves.

Army ROTC Building, Niagara University, Niagara, New York

The Peddie example is just one example, but I think it generalizes. If so, it illustrates at least two things.

One is the nonsensicality of the claim that we live amidst ubiquitous “wokeness.” We don’t, and never have. If we did, Veterans Day commemorations like Peddie’s or Princeton’s would not be taking place at putatively liberal institutions like Peddie and Princeton. Genuinely liberal institutions would be asking “woke” questions more in keeping with the original spirit of Armistice Day, like: Was all that warfare really necessary? If not, why did we engage in so much of it? Shouldn’t we be more vigilant about the lies we’re told by our governments, so that we can be ready for the next time they try to deceive us into war?

But such questions are rarely if ever asked. Peddie is not at all unique in this respect, but entirely pedestrian and commonplace. Its Veteran’s Day ceremony is just like Princeton’s, which is itself just like that of so many other schools and universities. It was like this at the dozen schools where I taught during my 26 year teaching career, like this when I attended both Princeton and Notre Dame for over a decade, and like this when I went to prep school for six years. That’s over forty years of personal experience in the American educational system. As far as warfare was concerned, there was nothing woke about any of it.

When I taught college between 2001 and 2020, a significant proportion of my students were military veterans, attending college on the GI Bill. Faculty were explicitly and repeatedly told that it was not only a legal infraction to discriminate against them, but an infraction to criticize their military service, or bring up any topic that was upsetting to them. I’m not sure in what universe any of that counts as “wokeness.” Since 9/11, the federal government has paid out $400 billion in veterans benefits to 25 million beneficiaries. Paying people for killing people doesn’t strike me as expressing the ordinary meaning of “wokeness,” either. What DEI program competes with veterans benefits for scope? The comparable alarmist figure for federal DEI spending is $1 billion. If $1 billion in DEI spending implies a “culture of wokeness,” what does 400 times that on the reverse side imply? But frankly, all of this is nitpicking. You don’t need quantitative evidence to figure out that wherever you go in American life, you find a consensus as to the sacred righteousness of our armed forces, their mission, and that of our allies, above all, Israel. Just contradict the sentiment in any context where it’s asserted, and see what happens.

Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland

The other lesson illustrated is the double standard that now prevails when it comes to talk about “viewpoint diversity.” When the topic comes up nowadays, we’re asked to believe that the fundamental problem concerning viewpoint diversity lies with the under-representation in educational institutions or society in general of right-wing ideas. Left wing ideas have prevailed for too long, goes the complaint, and it’s time to give right-wing ideas a chance.

This claim flouts reality. The United States has, by a very conservative estimate, been almost constantly at war for sixty years, starting the warfare clock (again, very conservatively) at 1964, with Vietnam. We could, of course, go a lot farther back, indeed, up to and prior to the founding of the country itself. But sixty years is long enough to make the point. There is a consensus in this country that we are, whatever our “policy disagreements” about any given war, obliged to fall in and support the troops no matter what. Just war? Unjust war? No matter. They’re all wars fought by our troops. We’re all Americans. We thus owe it to them to support them, particularly when “we” send them to fight wars that make no sense. That’s the unspoken premise behind Kinsella’s speech.

Question for the “viewpoint diversity” complainers: Where anywhere is the reverse of that sentiment institutionalized in American life? Where, in other words, can you find an institution where it’s taken for granted that the United States is a militaristic, aggressive, imperialist regime, that we have no obligation to support its wars, no obligation to support its troops and that we have instead an obligation to oppose and stop just about everything the US Armed Forces are currently doing?

F. Edward Hébert, founder of the F. Edward Hébert School of Medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland

Marginal groups aside, nowhere. Not in industry. Not in law enforcement. Not in health care. Not in journalism. Not in religious life. Not in the K-12 system. And sorry, not in higher education, where ROTC and military recruitment are commonplace, as are gigantic investments in military research, as are gigantic contracts with the military, as are academic appointments for military personnel. Not in the military itself, obviously, and not in ordinary conventional life, where every other flag pole flies a POW MIA flag, every other bumper sports a military bumper sticker, and where it’s commonplace (at least within my social circle) to engage with people who either are enlisted in the military or whose close relatives are.

So what are these proponents of “viewpoint diversity” complaining about? How can sixty years of consensus on the imperative of warfare, and sixty years of militarist propaganda, and sixty years of a digitized military-industrial complex constitute a left-wing chokehold on our intellectual life? How did that chokehold manage precisely never to prevent a single war from taking place in the actual, physical world no matter how loudly its exponents have screamed their dissent? If there is such an over-representation of left-wing ideas in the United States, and military restraint is one of them, how is it that the proponents of warfare have prevailed every single time in every instance when warfare has been proposed, no matter how bad their arguments, no matter how disastrous their prescriptions, and no matter how often they’ve gotten things wrong? How can a supposed monopoly on our lives exert zero power to effect any actual outcomes in the real world?

Chesapeake House, near North East, Cecil County, Maryland

Even if it were somehow believable to claim that higher education was a bastion of anti-imperialist pacifism–which it obviously is not–it would function as one small, still voice against a high decibel chorus of militarism. How is that–a tiny, marginal speck of dissent against a background of nearly universal conformity–a problem that requires a solution? And if it’s a problem, how is it a problem that requires greater resources and opportunities for the proponents of warfare? How much longer, exactly, do we need to give warfare a chance?

For more than a decade, between about 2002 and 2017, I made a point of donating a piece of every paycheck I earned to the Walter Reed Society, an organization devoted to the medical support of military veterans. I was a temp and an adjunct for a lot of that time, but I managed in the end to donate $5,000 and become a Life Member of the Society. Every year, I would attend the Society’s annual luncheon at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Bethesda, where the officers of the Society came to recognize me by face and name. And every year, they would publicly acknowledge and commend my efforts.

It took a little longer than a decade before I began to grasp the pious stupidity of what I’d done. The whole idea of becoming a Life Member of the Walter Reed Society presupposed that it was perfectly justified to send soldiers into combat wherever our rulers decided to send them. The only problem requiring a solution was what you did with them when they came back in pieces. The solution at Walter Reed was a version of the one in Alice in Wonderland: in a grotesque re-enactment of Humpty Dumpty, you put together in the OR and the rehab room what you yourself had broken to pieces on the battlefield. Soldiers would come by the luncheon to display the prosthetic limbs that our donations had bought them. Only gradually did it dawn on me that we had all bought a lot more than that.

Edgemont Park, Montclair, New Jersey

What students need today, more than anything, is an education by educators who see the insanity in all of this, and are ready and willing unapologetically to come out and say so. They don’t need “neutrality.” They don’t need mealy-mouthed agnosticism. They don’t need a renewed commitment to “viewpoint diversity” or “fairness” to the defenders of Boeing, Lockheed, Palantir, Microsoft, Oracle, Google, Mossad, ICE, or the Pentagon. Students need to engage with full-fledged partisans ready, willing, and able to shatter the dogmas in which they’ve been indoctrinated all their lives. They need to see that they’ve been lied to, and that good intentions are not enough to break the illusion.

Edgemont Park, Montclair, New Jersey

It’s not enough, Mill writes in On Liberty, that a person “should hear the arguments of adversaries” from neutral third parties, along with neutrally-presented refutations.

This is not the way to do justice to the arguments, or bring them into real contact with his own mind. He must be able to hear them from persons who actually believe them; who defend them in earnest, and do their very utmost for them.

The keepers of our educational system need to be reminded, at top volume, that such people really do exist. They need to be reminded of the value of hearing them speak in their own unfettered voice in wholehearted defense of their first-personal convictions. They need to be reminded that there is a war to be fought as a pre-condition of sending anyone out to battle against any enemy, foreign or domestic: the war for the moral high ground. They need to confront the fact that that high ground is contested territory, not to be ceded to anyone in a spirit of blithe insouciance. It has to be fought for, and control of the summit has to be earned. What they can’t pretend, or be allowed to pretend, is that pretenders and imposters can claim the summit by fiat. The history of warfare is a lesson in the falsity of that claim. You can deny it, but you can’t escape it–except at the price of self-destruction. If only we could ask the victims for confirmation. Too bad we can’t.

I cannot praise this article, enough, Irfan.

I would add a fourth “alternative remedy for the soldier-suicide problem”: Kinsella can quit his job as a financial analyst, and acknowledge to himself, and teach to others, that capitalism is the driving force for war. If there were not profit to be made by those who, since the origins of organized human societies and wealth accumulation, have sent others off to kill and be killed, the primary motive for war would disappear—as would the war profiteer class.

LikeLike

Thanks. I certainly agree with your general point. I think Kinsella left his financial analyst job in 2018.

https://www.goldmansachs.com/alumni/spotlight/2024/q-a-with-brian-kinsella-co-founder-and-chairman-of-stop-soldier-suicide-co-found

It’s amazing how much uncontested war propaganda surrounds us every day. Every day this regime expects us to sign on to the idea of killing some new population. One day it’s Gaza. The next day it’s Yemen. The next day it’s Iran. The next day it’s Venezuela. Tomorrow it will be China. There’s no end to it, in any sense of “end.” And everywhere you go, supposedly respectable institutions like Peddie and Princeton underwrite and normalize the psychopathy.

If all I can do is contest it, that’s what I’ll do. I’m still working on a piece on my own prep school, Pingry. There’s no shortage of targets.

I’m only too conscious of the connection between capitalism and the military. The company I work for is owned by the Carlyle Group.

https://publicintegrity.org/national-security/investing-in-war/#:~:text=From%20its%20founding%20in%201987,missile%20launchers%20and%20precision%20munitions.

If I could escape it all, I would.

LikeLike