We’re reading Hayek’s famous paper, “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” in our monthly reading group tomorrow. I’ve never been convinced by Hayek’s argument, and get less convinced every time I re-read the paper. I don’t have time to work out a full response to the paper, so here, for whatever it’s worth, is a quick laundry list of objections to be developed at some later date. Continue reading

Tag Archives: epistemology

Engels on Social Murder

“Social murder” is a form of homicide that takes place through relatively invisible social processes involving collective rather than individual responsibility. The concept is controversial because it attributes murder to “society” while relying on an unconventional conception of murder: society intends murder, and society kills, where society is identified with a ruling class that controls the political system. What’s controversial here is that social murder kills mostly by omission rather than commission, and is perpetrated by a class rather than by individuals. Both assumptions flout the conventional understanding of the intentionality and causality of murder. Continue reading

Desert and Diligent Paranoia

Suppose that a person is diligently paranoid. In other words, imagine a person who, by conventional standards, worries excessively about risks that involve low probabilities but high stakes. Imagine this person’s applying the precautionary principle in ways most people find problematically risk-averse. And imagine her actively planning for exigencies or emergencies in ways that consume emotional and material resources, thereby undercutting her capacity for ordinary enjoyment. Where most people would simply overlook these remote but apparently scary risks, the diligent paranoid expects them, planning and drilling for them, rehearsing what she would do when (not if) they come to pass. Indeed, diligent paranoids seem to feel a certain gratification when disaster occurs, since it confirms their irrational belief that life is a series of disasters. They appear to lead a problematically joyless existence, focused on mere survival rather than on a richer conception of human flourishing–the classic case of the person who lives her life by fear rather than some more wholesome motivation.

Continue readingIn Which I Predict That a Certain Event Will Happen

To anyone interested in the following session of the Auburn U. Philosophical Society, Friday 6 November at 3:00pm Central (= 4:00 Eastern = 2:00 Pacific), you’re welcome to join us by Zoom. Sessions usually run from between 90 mins. to 2 hrs., with the first half devoted to presentation and the second half to Q&A&A (questions & answers & argument).

Speaker: Dr. Dilip Ninan (Tufts U.)

Title: “Assertion, Evidence, and the Future”

Abstract: “In this talk, I use a puzzle about assertion and the passage of time to explore the pragmatics, semantics, and epistemology of future discourse. The puzzle arises because there appear to be cases in which: one is in a position to assert, at an initial time T1, that a certain event E will happen; one loses no evidence between T1 and later time T2; but one is nevertheless not in a position, at T2, to assert that E happened. I examine a number of possible explanations of this phenomenon: that assertions about the past give rise to an implicature about one’s evidence that are not carried by assertions about the future; that assertions about the future are not “categorical” in the way assertions about the past are; that one can lose knowledge of a fact F when then the passage of time transforms F from a fact about one’s future into a fact about one’s past. I argue that the third of these approaches is the most promising, and attempt to develop a specific version of it in some detail.”

Attendees are being asked to register beforehand. In other words, the link below is NOT the link to the meeting. Instead, if you follow the link below, you’ll be asked for your email address. Once you submit it, the meeting link will be emailed to you. You’ll need to make sure you register before the talk.

https://auburn.zoom.us/meeting/register/tZIsf-uorTwuHd1EObDf1zlfJgE1d4xz8zPI

MLK: “Believe Women,” Rape, and the Worst-Case Scenario

Yesterday, I wrote a post arguing that the supposedly woke slogan “Believe Women” has some odd implications for the recent Sanders-Warren controversy. It implies that we should believe Elizabeth Warren’s accusation that Sanders is a sexist, or at least presume his guilt until he can conclusively prove his innocence. Because I take this consequence to be a reductio, I take “Believe Women” to be an absurdity. Put charitably, the original, unqualified version of the slogan has to be modified. Put uncharitably, it has to be rejected. To split the difference, it requires a bit of both. Continue reading

“Believe Women Except When…”

So whatever happened to the “Believe Women” mantra, brought to us care of #MeToo? Yesterday’s unqualified axiom seems to have been washed away by today’s intra-progressive controversy. The reasoning here seems to be: Elizabeth Warren accused Bernie Sanders of sexism. But Bernie is more progressive than Liz. So the accusation can’t possibly be true, because if it were true, its truth would ruin the most progressive mainstream candidate’s shot at the presidency. Hence the accusation must be false, and Elizabeth Warren is a bit of a bitch for making it. From which it follows that the “Believe Women” axiom must also be false, though we’re not to say so out loud.

Gee, that was easy. Who knew that moralized axioms could so lightly be adopted, and so lightly be cast aside? Continue reading

How “We” Achieve Ignorance

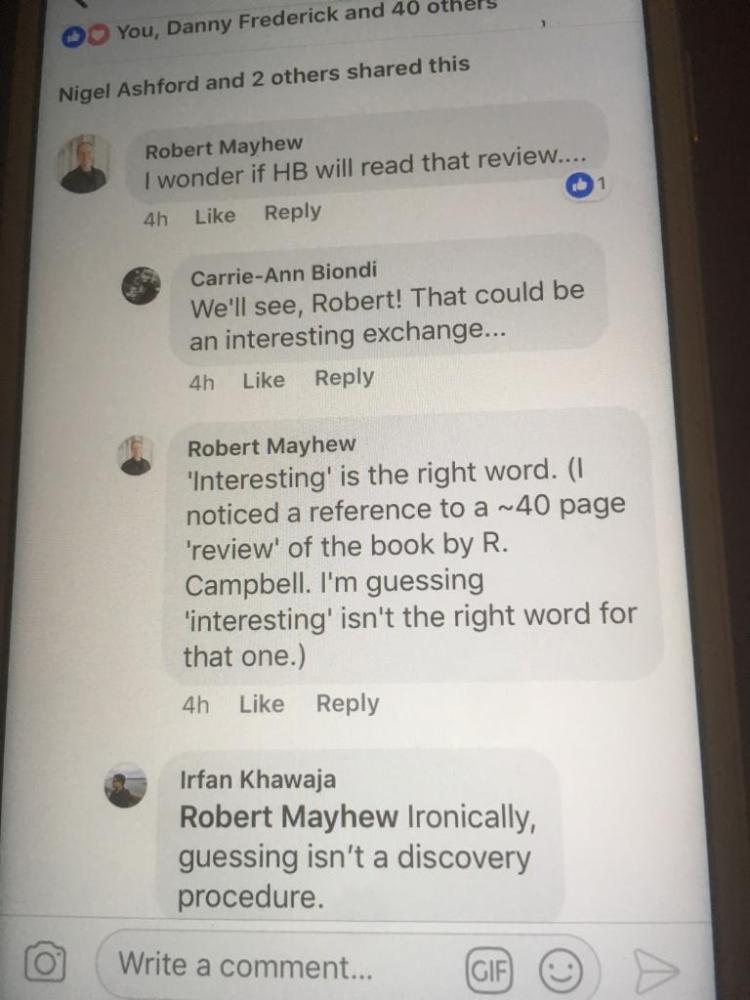

Here’s a Facebook thread, featuring arch-Objectivist Robert Mayhew (Philosophy, Seton Hall University, and Board of Directors, Anthem Foundation), discussing a newly-published review in Reason Papers, by Ray Raad, of Harry Binswanger’s book, How We Know: Epistemology on an Objectivist Foundation. In the last of his comments, Mayhew refers to Robert Campbell’s review (sarcastically dubbed a “review”) of Binswanger’s book in the Journal of Ayn Rand Studies.

There it is on display–the vintage ARI-inspired intellectual slovenliness, the reflexive resort to sarcasm, the unargued dogmatism, and the all-consuming desire to poison the well for The Tribe. Epistemology on an Objectivist Foundation: res ipsa loquitur.

What an asshole.

Law Enforcement, Philosophy, and the Ethics of Belief

From an article on the recent “swatting” case in Wichita, Kansas:

The law allows the police to use deadly force when an officer reasonably believes, given the information at the time he pulls the trigger, that his life or someone else’s life is in imminent danger. The Wichita officers had been told, wrongly, that they were encountering an armed hostage-taker who had already killed one person and was threatening to burn the house down.

“Nine-one-one is based on the premise of believing the caller: When you call for help, you’re going to get help,” Chief Livingston said. The prank call, he added, “only heightened the awareness of the officers and, we think, led to this deadly encounter.”

The antinomies of legalistic reason: The first paragraph tells us that the 911 caller made an accusation of criminal activity. But according to one prominent line of legal reasoning, an anonymous telephone-based accusation at best establishes reasonable suspicion of the commission of a crime–and usually requires a “totality of circumstances” test that conjoins the claims made in the call with facts observed or gathered independently of the call (see Lippmann, Criminal Procedure, pp. 107-109, 139-40, 2nd ed.). Continue reading

Underexposed

From a letter in today’s New York Times:

To the Editor:

Not to be overlooked in this stunning victory is the role of the investigative reporting done by The Washington Post. Despite constant excoriation by President Trump and the extremist Steve Bannon, the free and fair press exposed an alleged child molester. This played no small part in Roy Moore’s defeat.

The need to vigilantly support truth and accuracy in the media gets stronger every day.

ADAM STOLER, BRONX

Can you really expose an alleged child molester–as opposed to giving exposure to allegations of child molestation? To “expose” something is to reveal what had previously been hidden. But if someone’s status is alleged, what is said about him remains hidden. It makes no sense to say that you’ve exposed the hiddenness of what is hidden. But nonsense has now become par for the course on the subject of allegations.

I’m glad that Roy Moore was defeated. I’m not glad that we seem to have lost even a vestigial sense of the fact that an allegation is an assertion in need of proof, that people are innocent until proven guilty, and that proof is easier in the asserting than in the doing. But apparently we have, and solecisms like “exposed alleged child molester” are the result. The issue here isn’t Roy Moore per se, but the widespread loss of the skepticism required when allegations of wrongdoing are made, whether criminal or otherwise. (Incidentally, I for one wouldn’t celebrate at the thought that the only reason Moore was defeated was that he was alleged to be a child molester. Doesn’t that imply, pathetically, that had no such allegations been made, he would have won?) Continue reading

What Mary Never Did Know; or, How Kant Was Right

A well-known argument, due to Frank Jackson, goes as follows. (You can read the short version here.) The brilliant genius Mary has complete knowledge of physical reality. All the sciences, physics, chemistry, neuroscience, etc., have been completed—there is nothing more to add—so that the fundamental physical constituents and causes of all phenomena are known, together with everything that supervenes on them, and Mary has mastered all of this. But although Mary thus knows everything about the physical world there is to know, she does not know everything there is to know. For, a peculiarity about Mary is that she has lived her entire life in a black and white room and has never been permitted to view anything except in black and white. Thus, on the day when she finally leaves her room and sees, say, a red object, she will learn something she didn’t know before. She will say, “Ha! So that is what seeing red is like.” If this is correct, then, apparently, red, or the experience of seeing red, is not part of physical reality.

The “Mary” argument is just one of several ways to bring out what is really an old, classic problem with any sort of reductionistic physicalism. It is this. Continue reading