“Divestment and the Boundaries of Conscience”

As regular readers of this blog know, I’ve been involved since 2024 in the campaign to induce Princeton University to divest its holdings, not just from Israel, but from arms manufacture and military affairs as such.

It was about a year ago that I got it into my head to get Robert K. Massie IV involved in our efforts. Massie is one of the architects and chroniclers of the decades-long campaign to divest from apartheid South Africa; I’d first encountered his book Loosing the Bonds twenty years ago, and been impressed by the rigor of his argument, as well as by the wealth of detail and moral passion he brought to the subject.

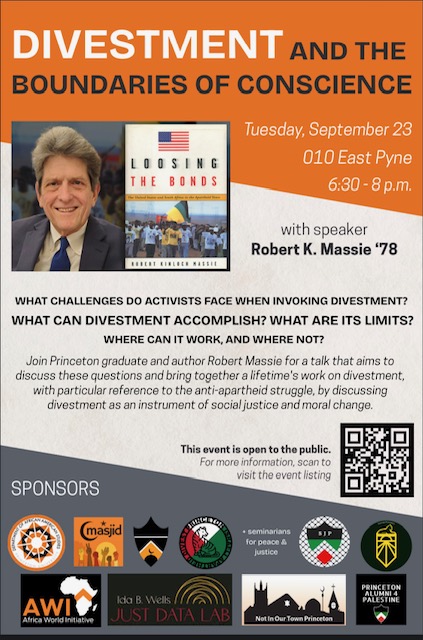

My hope was to invite Bob to speak, less on Palestine per se than on the very general topic of divestment as an instrument of moral progress. That effort finally came to fruition last week, culminating in a talk on campus called “Divestment and the Boundaries of Conscience.”

A candid settler in Hebron, August 2019 (photo: Irfan Khawaja)

In scheduling the talk, we–Princeton Alumni for Palestine–were uncomfortably aware of the fact that it fell on the first full day of the Jewish New Year. There was, unfortunately, no feasible way around that. The talk was meant to precede the September meeting of Princeton’s Board of Trustees, the point being to give them a copy and invite them to engage with the argument. Our first choice was to schedule the talk for the 25th, the day after Rosh Hashanah–except that Bob had a set of prior commitments at Columbia on that day and for the next few. So the 24th it was.

Luckily, what began in bitterness was dipped in honey and came out sweet: after arriving in Princeton from Massachusetts, I drove Bob over to Campus Club on Monday night, where the Alliance of Jewish Progressives (AJP) was holding its Rosh Hashanah dinner.

Thanks to Abigail, Charlie, Elena, Zac, and of course everyone else at AJP for making this happen, and for making it so memorable for both Bob and me.

The talk was scheduled for the following evening. As it happens, Bob is both a Princeton grad and an ordained Episcopalian minister, so the trip back to campus–and to the University Chapel in particular–had both a nostalgic and a spiritual dimension.

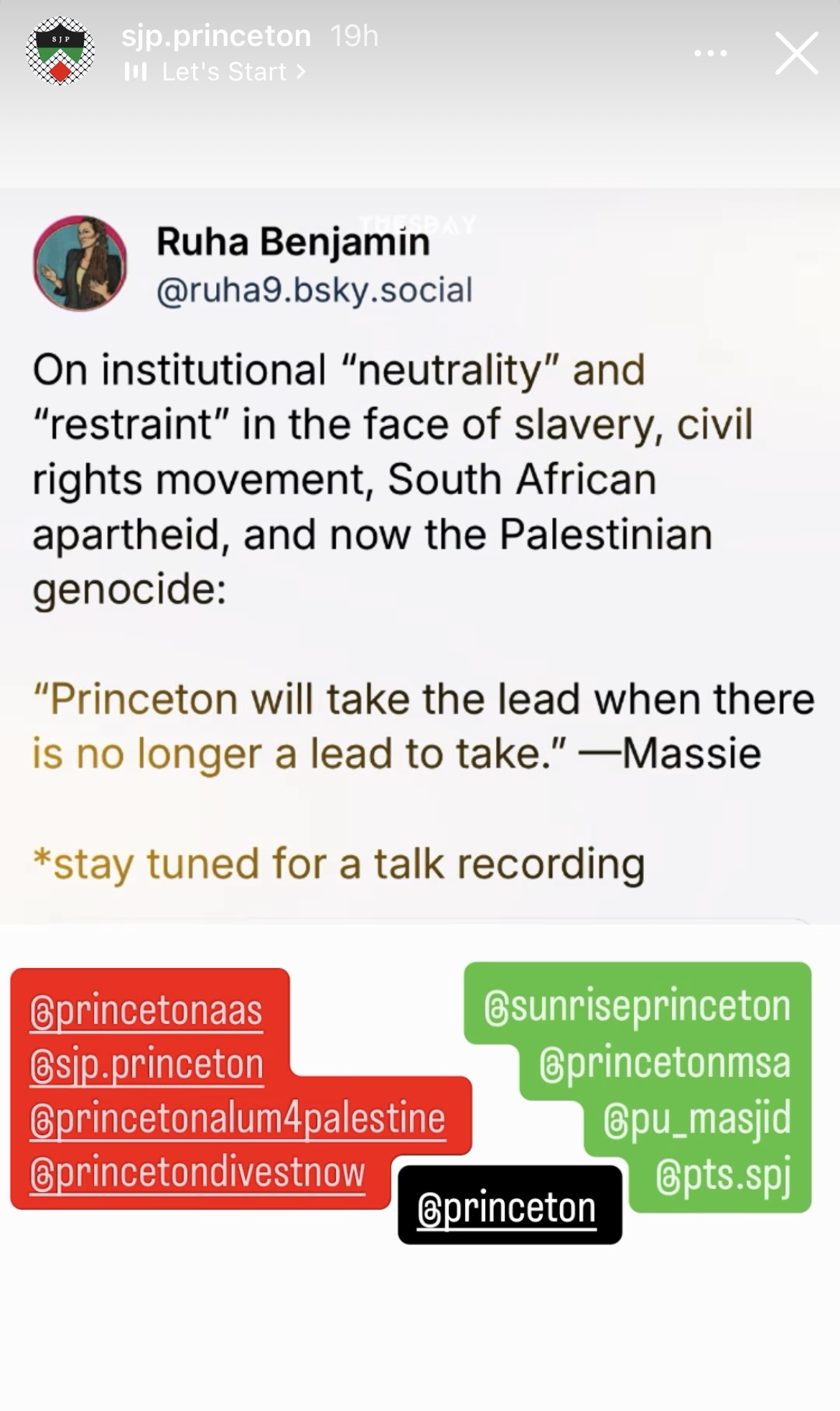

The talk itself took place in East Pyne 010, a medium-sized auditorium meant to seat about 100. We filled it to capacity and then some: standing room only. My co-organizer Ruha Benjamin gave the welcome, alluding in it to the fact that September 23rd was the birthday of the recently martyred Palestinian poet Rifaat Alareer, and passing around a bowl of strawberries to mark the occasion. SJP’s Givarra Abdullah gave a pitch for SJP Princeton, and Sunrise Princeton’s Isaac Barsoum gave a memorable pitch for Sunrise and for the climate. As per usual, I came up with a somewhat outlandish introduction (reproduced below), and then Bob took it away, bookending his talk with a Jewish prayer and an Islamic one. We had a stimulating discussion in East Pyne, and then a longer one over dinner at Winberrie’s nearby.

Bob is polishing up a written version of the talk, which will be made available as soon as we can manage. My own view is that the paper should eventually be published somewhere so that it gets a wider audience than it’s so far gotten. The argument Bob makes is provocative, urgent, and well-conceived. Though I don’t agree with every move or every sentence, there’s more than enough in it to think about and act on.

At a bare minimum, Bob is a living, breathing refutation of the nonsense one so often encounters nowadays about the incompatibility of activism and scholarship. No purely cloistered scholar was likely to have the kind of detailed, hands-on, first-personal knowledge that Bob has of this intensely interdisciplinary subject. In a quarter of a century in higher education, I don’t think I’ve ever encountered anyone with a better talent for converting how-to knowledge into propositional form.

Here, for whatever it’s worth, is my introduction:

Hello everyone,

I’m very pleased to see everyone here, and very pleased to be here. My name is Irfan Khawaja; I’m a Princeton alum of the Class of 1991, and an organizer with Princeton Alumni for Palestine, the alumni wing of Princeton’s Palestine solidarity movement. I’m honored to have the task of introducing our speaker, Robert Massie of Columbia University, and I suppose the best introduction to Bob is to describe my own introduction to him.

No one who lived through the 1980s, as I did, can forget the moral gravity of the struggle over apartheid South Africa. As a high school student, I was a loud and vociferous defender of divestment, and yet when I got to Princeton, all of that changed: I found myself oddly paralyzed, oddly cautious, oddly tied in knots. I turned away from activism, and watched with sympathy but didn’t join in any of the campus protests over divestment. Eventually, like a character in a Kafka novel, I woke up one morning and found myself the editor of The Princeton Tory. It was bad.

After I went to grad school, I came back to the Princeton area and started teaching philosophy at The College of New Jersey. One day, I got into an argument about the WTO protests in Seattle with a colleague there, the late Mort Winston, then Chair of Amnesty International’s Standing Committee on Organization and Development. Mort was a blunt guy, and told me in no uncertain terms that my political views, particularly about activism, were deeply ignorant and fucked up, and that the only remedy was to read Robert K. Massie’s 800 page book, Loosing the Bonds, on the divestment campaign from apartheid South Africa, which I did. It took a while, but when I got to the end, I realized that Mort was painfully and profoundly right.

That was more than twenty years ago. The book led not only to a re-appraisal of my arguments, but a re-appraisal of my life. It led me to wonder what had gone wrong, not just with a belief or two, or an argument or three, but with me. And though I didn’t personally know Bob at the time, a large part of that inquiry raised questions more personally fraught than anything about divestment and apartheid. I’d wanted to become a cloistered academic, not an activist. Why? What for? What exactly was I afraid of?

Much of that answer is TMI, but the salient part is not. It is possible to enter a milieu like Princeton and be neutralized by its selective pretensions to neutrality. It is possible to come with the best of moral intentions and yet be anesthetized by others’ desire for moral sedation. It is possible to have suffered greatly in life and feel the need to hide in libraries and lecture halls, locked in the safe embrace of books and words and arguments.

What I’ve learned from Bob over the last twenty years is not confined to history lessons about Princeton or South Africa, or prudential lessons about institutions and divestment and the rest, important as all that is. The deepest lessons have been moral. For one thing, that moral engagement is an imperative, because there’s nowhere to hide from it. For another, that it’s possible to go wrong, deeply wrong, in life, but possible and imperative to come back.

If I can, Princeton can. If Princeton can, anyone can. I leave it to you to decide how that applies to you. Without further ado, Robert Massie.

****

The next morning, I put Bob on the 7:26 am New Jersey Transit Express to Penn Station–along with maybe a thousand other commuters at Princeton Junction. Squint hard and you’ll see him.

The NJT 7:26 am express

I expressed some worries about the logistics involved. He told me to “have faith in the goodness of humanity.” He got to Penn Station, and got to Columbia. QED.

I want to acknowledge the many, many people who helped make this event a success, above all our team at PA4P whose dedication and example keep me going when I’m inclined to lie down on the job. A huge thanks also to Ruha Benjamin and the Department of African American Studies, which co-sponsored the talk with us, along with a very long list of co-sponsors, listed on the flyer, whose support and solidarity were enormously gratifying. If I’m not more specific about naming names, it’s only because given current realities, I can’t be sure whether doing so would harm or benefit those I name–one of many realities that our campaign is intended to reverse. Here’s to the hope of moral progress in the new year.

Activist Sireen Sawalha, of Jenin, at the weekly Gaza Solidarity rally, Palmer Square (Sept. 28, 2025).

Pingback: Activist Interviews: Emanuelle Sippy | Policy of Truth