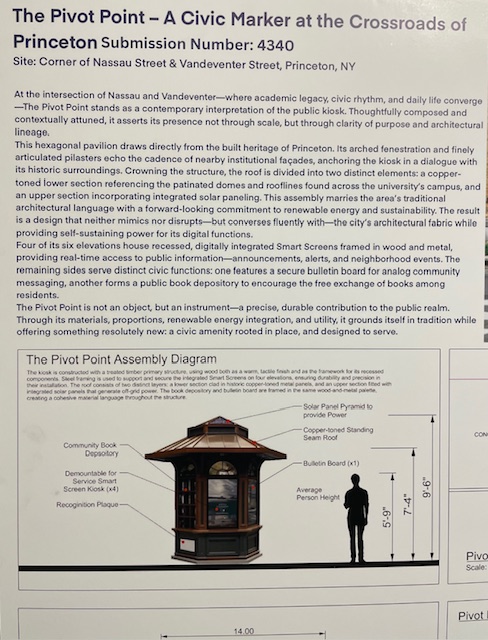

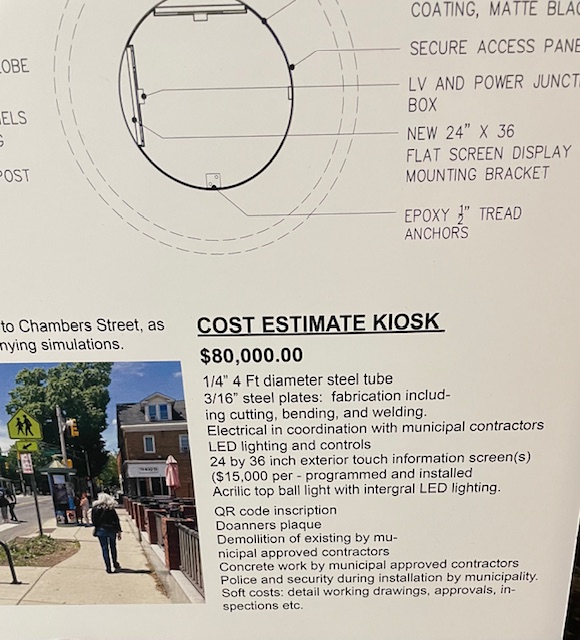

It’s a good day, just really cold. I go to the gym. I get my hair cut. I go to the public library, and get some books to read. On my way out, I stop by an exhibit displayed with great pride in the lobby: the municipality is tearing down the lo-fi flyer kiosks in town and replacing them with hi-tech versions, at an estimated cost of $80,000. Stupid, I think. Expensive, vain, and pointless–but typical.

It’s dark now, and even colder than it was when I left the house–somewhere in the 30s. I’m annoyed at the prospect of having to bike home in the cold, but it’s festive in the square, and for a minute or two, even I manage to feel a bit of holiday cheer, Scrooge that I am.

I turn a corner and hear sobbing in an alley. I recognize it: it’s the same homeless person I housed for awhile about a year ago. I temporarily went broke last year putting her up in a Holiday Inn. Yes, a few days at the Holiday Inn is enough to clean me out, at least until my next paycheck. Embarrassing but true: I may be a revenue manager, but none of the billions of dollars I manage is mine.

I think about doing it again, but don’t. I need the money for the annual trip to my girlfriends’ parents’ house this Christmas. It’s a long-distance relationship, and we only see each other a few times a year. If I spend the money now on a hotel room, I’ll kill the trip and ax my relationship. There’s only so many times I can do that sort of thing, and I’m now past my ninth life as far as relationships are concerned. It’s a lame excuse, but it’s all I’ve got tonight, so I use it. I walk quickly past the person I’m abandoning, unlock my bike, and start pedaling. Unlike her, I have gloves to wear and a place to go. It’s cold, but in ten minutes, I’ll be home. In ten hours, I think, she might well be dead of hypothermia.

Homeless people are hard to help, I’ll give myself that. God knows I tried last year, but it didn’t work. Every suggestion I made went rejected or unheard, so eventually I gave up. “I can’t keep paying for the hotel past tomorrow,” I said. “I’ll pick you up at 10, and drop you off in town. I can pay for a meal at that point, but that’s it.” And that’s how we played it. “Where do you want to eat?” I asked. “Would the Noodle House do?” Sure she said, with obvious irritation. “That’s fine but don’t call it that.” “Call it what?” I asked. “Noodle House,” came the response. “You don’t have to use that word when you’ve got one and I don’t.” I took the point. “Noodle Place” it became.

The funny thing is that I was homeless myself just five years ago. Just a lot luckier than this person. One set of friends took me in for nine months, and another has given me a room to live in for the last four years. At no point was I exposed to the elements for longer than an afternoon. But put one thing out of joint, and I’m out on the street myself: my first benefactor died in a freak traffic accident a week after I left her house, dying before I was ever able to thank her for putting me up. There was, naturally, no way for me to afford a Jersey rent, and there still isn’t: it was either charity or the homeless shelter, and I consistently went with the first. You’d think that a person so close to the edge would be more generous to people over it, but no. Sometimes, the closer you are to the edge, the more you hoard your good fortune. I state that as a generalization, but it sounds a lot like a confession.

The idea of fraternity, Rawls writes, is that of “not wanting to have greater advantages unless this is to the benefit of others who are less well off” (A Theory of Justice, p. 90, rev. ed). As for justice: “Those who have been favored by nature, whoever they are, may gain from their good fortune only on terms that improve the situation of those who have lost out” (Theory of Justice, p. 87).

It’s hard to see how either thing is being exemplified here, fraternity or justice. As far as fraternity is concerned, I don’t really want my greater advantages unless it’s to the benefit of those less off, but I’m not about to give them up, either. And when it comes to justice, I’m hard pressed to figure out how my good fortune in a heated room with electricity improves the situation of a homeless person downtown. I console myself with the thought that fraternity is just a metaphor, and that Rawlsian justice is more structural than personal: once the structure is just, you’re mostly off the hook. But it all rings hollow, all verbiage refuted by the cold.

The less flowery truth is that there just seems a limit to the demands I can satisfy, however legitimate, and tonight I’ve reached them, if only in the sacred names of solvency, warmth, and convenience. “Am I my brother’s keeper?” Cain asks God under interrogation, the ultimate in moral insouciance. My guide tonight is Cain, not fraternity or Rawlsian justice. A terrible admission to have to make, but on nights like this, not one I can deny.