For years now, I’ve been railing against an argument of Jason Brennan’s concerning character-based voting. Brennan’s argument holds that when it comes to voting, unless a candidate’s character can be shown to be a proxy for the policies he’ll adopt, predictions about those policies should trump judgments about character. In other words, when it comes to voting, the policies you predict that a candidate will adopt are more important than any character-based fact or set of facts about his fitness for office right now.

I’ve argued for years that Brennan’s argument fails: it’s unmotivated and counter-intuitive. Unmotivated: he provides no compelling argument for it. Counter-intuitive: he can’t explain what’s wrong with deviations from it. As it happens, there are many cases in which deviation from the “policy>character” principle makes perfect sense. I’ll get to one in a moment.

I’ve given a couple of conference presentations on this topic, but have never written up a formal paper, partly because I have too much on my plate to do so, and partly because I know that time is on my side. The more I wait, the more the counter-examples to Brennan’s thesis pile up. The more the counter-examples pile up, the more material I have to work with. The more I have to work with, the less plausible his thesis.

The Henry Hudson Bridge from Inwood Hill Park, October 2017

But forget me: the more the counter-examples pile up, the more they’re noticed by experts in electoral theory. So I could die tomorrow but the problem for Brennan would remain. I keep at least sporadic tabs on the literature in electoral studies, and it’s clear that the tide is changing on this question. Experts who once confidently said that character-based voting was silly or sub-par are now changing their tune.

I get why. The experts’ confident rejection of character-based voting was ill-conceived from the start, based more on hand-waving condescension than on actual empirical evidence or a commitment to methodological rigor. There was just this vague sense that character is soft, whereas policy is hard, and policy is relevant whereas character isn’t. There was nothing to these dogmas but dogmatism, and they’re now falling apart. The rise of Trump has made this hand-waving harder to pull off: Trump’s unfitness for office is obviously relevant to the question of voting for him, whether or not it’s a proxy for policy; to deny that is a reductio.

Lower Manhattan from the Hoboken Ferry, April 2017

But this particular fact about Trump draws attention to more general ones, ones that should have been obvious from the start, but somehow weren’t. Consider a handful of them, between three and five, depending on how you count.

(1) Brennan stipulates in The Ethics of Voting that voters should, when voting, aim at the common good. The same stipulation applies, with intuitive plausibility, to electoral candidates themselves. If aiming-at-the-common-good is demanded of voters, then by parity of reasoning it must be demanded of candidates. But the propensity to aim at the common good is a trait of character, justice. If so, its absence is a strike against a candidate, regardless of whether or not you can specify the would-be connection to prospective policies. If the absence of a trait of character is a veto against a candidate regardless of its policy implications, we have a consideration in favor of character-based voting. It is, so we do.

(2) A clear application of or variation on (1): Candidates guilty of serious prior malfeasance are, or intuitively ought to be, excluded from office, whether or not the basis of exclusion is policy-relevant. A genocidaire should not be elected mayor of a township, even if there’s no chance of a repeat performance of his genocide (or anything like it) in the township. Being a genocidaire is in this context a proxy for a judgment of character, not policy. In this case, the presence of a trait is a veto against a candidate regardless of its policy implications–another consideration in favor of character-based voting.

(3) The underlying principle common to (1) and (2) is that political office is in part an honorific and in part a means of access to enormous perquisites. These have to be deserved to be properly received, and when they’re not, which is a matter of character, their receipt violates justice. Indiscriminate awarding of perks and honorifics is by itself a violation of justice, whether or not it affects policy. That, too, is a consideration in favor of character-based voting.

The Hudson from Fort Tryon Park, early fall 2017

(4) There’s also an epistemic problem. The predictions we make about the expected consequences of a candidate’s policies are (to put it mildly) highly defeasible. Judgments about character are likewise difficult to make, but certain red flags are visible enough. Suppose certain red flag judgments about a candidate function as a veto on his candidacy for office. It’s plausible to think that these red flag judgments will enjoy better epistemic credentials than any prediction about all-things-considered policy outcomes. If the candidate is a habitual liar, or a murderer, or a pedophile, that can be known with far greater certainty than what will happen to the economy, all things considered, if you push a button with his name on it in the polling booth. If the former consideration functions as a veto, the latter becomes irrelevant. But then it’s character that trumps policy, not the other way around.

(5) Finally, there is a sense in which certain judgments of character are so automatically proxies for policy as to render Brennan’s “only if it’s a proxy for policy” condition otiose. If someone promises you something, like a policy, you can only make predictions about the “expected outcomes” of the policy if you have reason to believe that there are expected outcomes. But you can only confidently believe this if you can confidently believe in the fidelity or veracity of the candidate making the promises. Fidelity and veracity are traits of character and epistemic pre-conditions for the reliability of any predictions you make about policy. In that respect, trust in someone’s fidelity or veracity is prior to and determinative of any prediction about policy. The only thing you can predict about a liar is that he’ll lie to you. You can only do better than that if you can reasonably predict that your interlocutor has a truth-respecting character orientation. If so, character is always a proxy for policy. Take it out of the equation, and all policy talk becomes gibberish.

The George Washington Bridge from Fort Tryon Park, May 2017

All of this is common sense, but much of it has until recently been missing from academic discussions of the topic, including Brennan’s. That’s changed over the last decade or so. Given this, specialists in electoral studies have, over the last decade, produced a substantial body of work that gives credence to the idea of character-based voting. The work they’ve done is good, but could always get better. I’m sure it will. I’m in no rush.

The New York City mayoral contest provides a perfect case study of the rationality of character-based voting. The race there is between Zohran Mamdani, Andrew Cuomo, and Curtis Sliwa. Let me sketch one reasonable way in which a person might decide between these candidates on the basis of character.

It’s certainly true that Mamdani, Cuomo, and Sliwa differ among one another on policy grounds. But suppose that you the voter were ignorant of these differences, or relatively indifferent to them, or simply didn’t believe that in practice, they’d matter that much. All you have to know is that as far as the predictable consequences of their policies, these candidates are roughly in the same ballpark, give or take. Yes, the media plays up the most sensational supposed differences between them, but that’s mostly hype. Yes, policy matters, but it’s complicated. So you could reasonably outsource the policy judgments to policy experts, and for your own part, make the decision to vote on non-policy-based grounds.

The only guide to policy you have, after all, is what the candidates say, and the only guide to the relation between what they say and what will actually happen in the world is a series of very defeasible judgments based on highly contingent matters. It’s not at all clear how anyone is to go about cutting through all of the contingencies to make these judgments, or if anyone really can. It’s not merely a matter of focusing on what the candidates’ campaigns are saying, but of taking an inventory of all the possible choices they might face in the future, then predicting what they would do, on policy grounds, about all of them, then predicting what would happen once you sum all of the consequences, then projecting the future consequences of that sum.

Brennan et al want you to believe that social scientists can do this. Even if this were true, it would leave unanswered which social scientists you should believe and why. Competent social scientists disagree about a lot of things, including whom to vote for. So absent a comprehensive litigation of every relevant social scientific controversy, and a workable electoral criterion for choosing which social scientists to believe, “#BelieveSocialScience” tells us nothing of value.

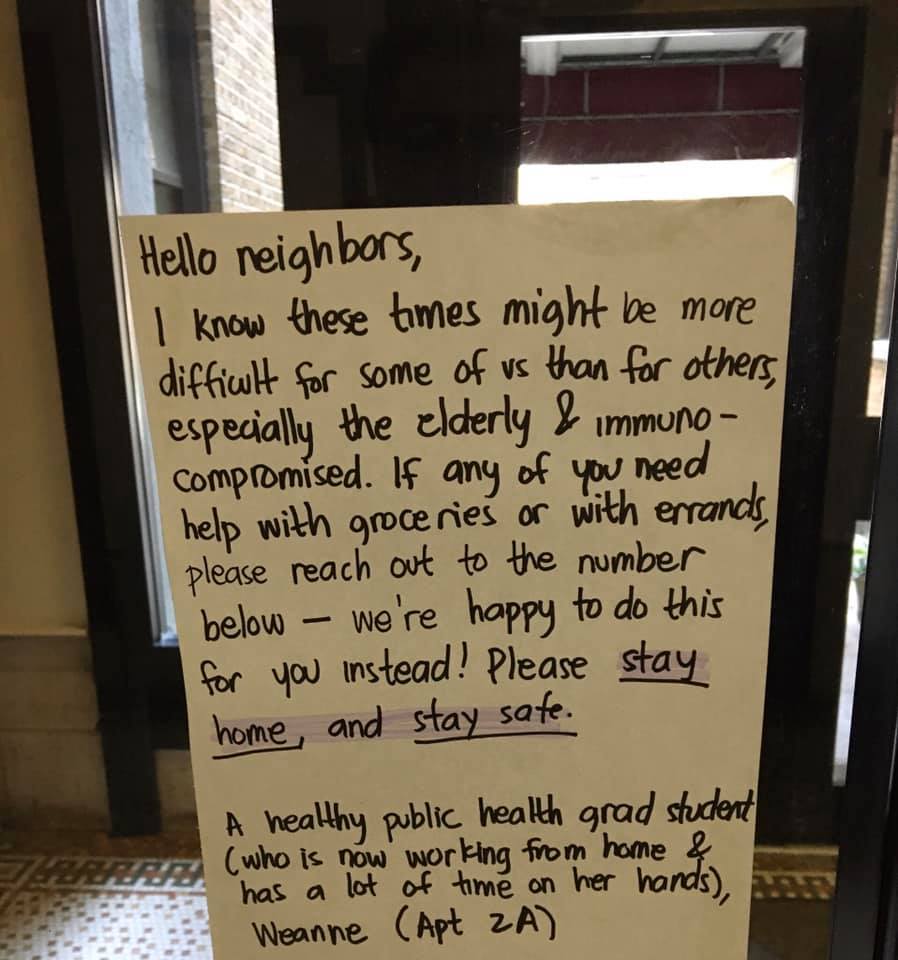

In the lobby of our building, 106 Cabrini Blvd, Washington Heights, April 2020

In any case, social scientists can’t make the relevant prediction. What we need is a scientifically rigorous way of predicting the comparative hypothetical results of a Cuomo vs. Mamdani vs. Sliwa election. The answer has to be determinate, has to take stock of exogenous shocks (pandemics, terrorist attacks, fascist take-overs of the country, etc.), and has to be an all-things-considered judgment that includes all relevant factors and all policies, taking stock of the causal route from the mayor to the world via every bureaucracy in the city. Newsflash: social scientists can’t give us this, and don’t claim to. They’re the ones telling us that they’re facing a replication crisis for much simpler, more artificial matters. So it’s not plausible to think that you can just ask ChatGpt “What does social science say about the all-in effects of a Mamdani mayoralty vs Cuomo vs Sliwa?” and out will plop the Key to All Electoral Mysteries.

I already did it for you, by the way. Here is the answer:

There is very little rigorous social-science that estimates the ‘all things considered’ effects of one hypothetical mayoralty vs another in New York City.

If there’s “very little rigorous social science that estimates all things considered effects,” we have no reason to believe that a knowledge of social science is a necessary condition of responsible voting. Ought implies can. You can’t be expected to consult what doesn’t exist.

One reasonable response is to think that predictions are hard to make, but none of these candidates can make radical, revolutionary changes to a place like New York City, whether for good or ill. Every policy issue that has been discussed as though its implications were self-evident involves some complexity that renders it less than self-evident. This is as true of the accusation that Cuomo got everybody’s grandparents killed during the pandemic as it is of all the mean-girl criticisms made of Mamdani’s supposedly disastrous proposals on free buses or subsidized grocery stores. Yes, some things will change at the margins, whether for good or ill, but the City isn’t going to be turned upside down, and how we figure out what changes is guesswork, not physics.

Cabrini Blvd, Washington Heights, April 2020

The hard fact is that most policy-making is an experiment, where you have to run the experiment to know what happens. No ex ante judgment will suffice. We can’t even predict whether the candidate will follow through on his promises, much less where exactly the promised policies will land over some indeterminate time period. So it’s senseless to exaggerate what can be known.

Given this, it’s fair to treat policy as a constant and also as a relative unknown. What you can know or assume is that each candidate will try to put his preferred policies into effect, but will run into obstacles that water down whatever he wants. None of the policies will be a panacea, but none an all-out recipe for disaster. You won’t really grasp their implications until after they’re put into practice and the dust clears. There are no crystal balls here, and certainly none in the possession of Jason Brennan or Bryan Caplan or 100 of their best friends. The issue is particularly difficult when you face an incumbent with a long track record in a given office as against a total newcomer with none. What evidence do you consult, even in principle? No matter how many Nobel Laureates in economics you have on your side, you’re either forced to guess about something important or to be agnostic about the whole picture.

Now look at the candidates. Here are some screamingly obvious character-based facts about them.

- Cuomo cannot be trusted.

- Mamdani seems trustworthy.

- It’s not clear what Sliwa stands for.

I’m not going to waste time proving this. If you don’t know this much, you don’t know anything about the race. As an addendum to (1), however, I will say in all candor that if there is another 9/11, I’ll be the first to celebrate it, as long as Andrew Cuomo is in the building the terrorists attack.

Suppose then that a voter votes for Mamdani on grounds of trustworthiness, which is a trait of character, against Cuomo on grounds of untrustworthiness, which is also a trait of character, and against Sliwa on grounds of unclarity, which, however you describe it, is a veto on his candidacy. In this case, you’ll have voted for Mamdani on grounds of character. QED.

The 9/11 Memorial, Lower Manhattan, May 2014

Maybe Mamdani’s trustworthiness is a proxy for the policies he’ll promote, maybe not. It doesn’t matter. If policy is taken as a constant in the sense I described, then trustworthiness beats untrustworthiness, and beats unclarity as well. That’s all you need to know. It’s not that hard to figure out.

How is that wrong? How is it not character-based voting? How is doing it beyond the capacities of the ordinary voter? In the absence of answers to these questions, Brennan’s argument fails, but I see no reason to think he has answers to them, and don’t think anyone else does, either. If he doesn’t, one argument he gives for electoral disenfranchisement fails as well. People don’t need to know as much social science as Brennan and Caplan et al claim in order to vote competently. Nor would voters be helped by that knowledge nearly as much as Brennan or Caplan seem to think.

The moral knowledge that most people have is sufficient to decide some important electoral questions, like this one, and not to be dismissed or denigrated as cavalierly as these “experts” want to do. The lesson here is that epistocratic disenfranchisement has a much steeper hill to climb than these disenfranchisers have grasped or bargained for. They should be forced to climb it all the way to the top before anyone gives credence to the patent injustices they demand.

This post is dedicated to my favorite New Yorker, Chris Sciabarra. Hope you feel better soon, and that the next mayor does you right.

predictions about those policies should trump judgments about character.

Ooh, you used a dirty word.

LikeLike

The only profanity I used in the piece was “Cuomo.”

LikeLike