A quick announcement of two talks I’m doing in the near future, both on health care. The first is called “Patient, Defend Thyself: Insurance Denials and the Resort to Force,” at the annual meeting of the Peace and Justice Studies Association (PJSA), Saturday, Oct. 11 at Swarthmore College. The second is a brief, untitled contribution to an Ethics Roundtable on access to health care, co-sponsored by the Association of Practical and Professional Ethics (APPE) and Felician University, Wednesday, Nov. 5, 1-2 pm on Zoom. The PJSA talk is on-ground and only open to registered conference attendees; the APPE/Felician talk is fully online and open to the public.

Given all that’s happening–genocide, warfare, the descent into fascism–it’s easy to lose sight of more mundane things, like health care. I saw a particularly myopic example of this the other day on Facebook. A well-known journalist worries out loud that the United States is becoming a military dictatorship, like “Egypt.” “Meanwhile,” she complains,

Dems are haggling over health care subsidies with a fascist regime instead of shutting it down.

Note the insouciant assumption here that “health care subsidies” are a mere frivolity that can take a back seat to more important concerns. Translated into plain talk, this says: “The lives of Medicaid recipients are dispensable. Absent access to subsidies, Medicaid recipients risk premature death or morbidity. But who cares about that when democracy and liberalism themselves are at stake?” This is the way people talk when they’ve always had access to health care, and have never had to imagine life without it. It seems not to have occurred to this writer that it’s hard to care about the prospects for democracy or liberalism when life itself is at stake.

The world looks very different to people in the reverse situation. Spend one day in any Emergency Department in virtually any hospital in this country, and you’ll see the relevant lesson enacted before your very eyes. Or spend a day poring over Medicaid denial data, as I did at work all of last week, and try to compute how much medically necessary care went denied across just one month at one area hospital: the same lesson quantified. If you’re really ambitious, try to put these two pictures together, and get a glimpse of the whole they make. Kudos if you succeed where most have not.

The war on Medicaid, like the war on migrants, is part of a broader war on the American people itself. The first targets of a war of this kind are those most vulnerable to attack, and (for that reason) those most ubiquitously the objects of popular contempt. Migrants are both vulnerable and objects of contempt because they lack the protections of citizenship. Medicaid recipients become vulnerable when they need medical attention they can’t afford; their compromised physical condition elicits one form of contempt, their need for financial assistance another.

Migrants on Medicaid combine these two predicaments–maximal precarity with maximal contempt. The only thing worse is to be a migrant not on Medicaid but in need of it. We often use the phrases “walking wounded” and “living dead” in a spirit of levity, but if you want a sense of their literal, non-humorous meaning, imagine the situation of someone who hesitates to call 911 in a medical emergency because they realize that while treatment is a medical necessity, it’s also an act of self-exposure. Illness elevates the risks of mortality and morbidity, but treatment risks bankruptcy, detention, and deportation. You couldn’t find a more literal example of a choice between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea.

If you want to condition a population to the destruction of sub-demographics within it, one place to begin is with the stateless, the unhealthy, and the financially strapped. Start by rendering their lives precarious. Proceed by heaping contempt on them for their inability to deal with it. Repeat the process until they really can’t deal with it. At that point, all you have to do is give them a little shove over the edge. Once they land, you’re free to pick new targets, and start over. The greater the number of targets, the longer the game.

The game goes on to the extent that the rest of the population feels the need to differentiate itself from the contemptible groups on the receiving end of state and corporate power. Migrants are stateless, but citizens are not. The unhealthy are weak and vulnerable, but the healthy are not. If you’re healthy, employed, insured, and a citizen (particularly by birth), it becomes easy to imagine that you’re immunized against misfortune or injustice by the presumptive combination of prudence and industry that put you where you are. You’ll never be a migrant or a Medicaid recipient, much less both at once. So you’re safe.

Maybe. But this is to misunderstand the logic of fascism. You don’t have to be a migrant or a Medicaid recipient to exemplify the properties that make them candidates for destruction. You just have to exemplify the properties themselves, and learn, the hard way, that there’s no such thing as immunity to destruction in a fascist state. You may not be an illegal, but there’s likely something illegal about you. You may not be a Medicaid recipient, but there’s always a chance that you’ll end up with a medical bill you can’t pay. Leave it to chance, time, and the industry of the malicious to do the rest. Either the odds get even, or the maelstrom passes you by. Good luck either way. Because luck is all you can depend on.

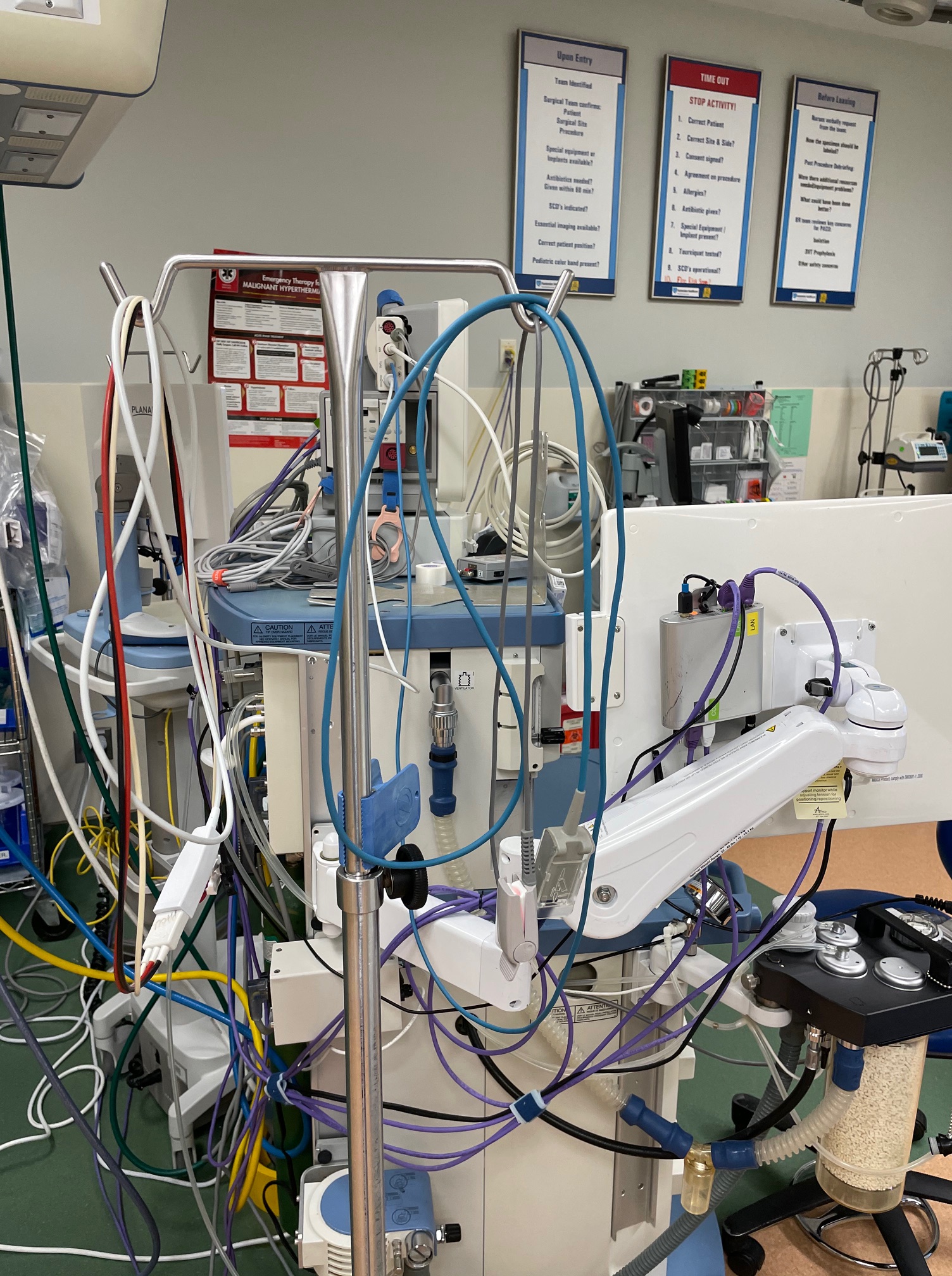

When I first lost my academic job, I made a beeline for health care, the only other field I know well enough to work in. I grew up in a medical household, had worked in health care before, and was at least passably comfortable with both the financial and clinical sides of health care: bills and EOBs on the one hand; needles and hazardous waste on the other.

I started out cleaning and setting up operating rooms, but found that I couldn’t make ends meet that way, then switched to health care revenue cycle management (RCM), and have been there since. RCM is the Byzantine process by which medical procedures become medical bills, and medical bills reach final disposition–paid in full, denied in part, unpaid, written off, or passed on. Every category is a bureaucratic drama of its own, a drama so complex that even as a daily practitioner, it takes effort to see the forest for the trees. I can’t say that I know every tree in the forest–no one does–but I have at least a basic sense now of the forest itself.

I figured when I started in RCM that it would take me five years to learn the business end of health care well enough to analyze it and explain it to others. It’s been four years and five months so far, and at a basic level, my initial prediction seems right; give me another seven months, and I might make it right.

That’s what I’m trying, however imperfectly, to convey in these talks–the business end of health care as seen by a moral philosopher. The first is an attempt to wrestle with the widespread ambivalence occasioned by Luigi Mangione’s shooting of UnitedHealthCare CEO Brian Thompson. The second is a more general attempt to discuss the relationship between insurance denials and access to health care.

In a way, the plea common to both is: don’t dismiss health care. Whatever the vicissitudes of our political situation, you have a body, it can fail, and when it does, you’ll need health care. Where access is assured, you survive or thrive to fight another day. Where it isn’t, you don’t. The body can’t be wished away by anyone on any side of any ideological divide, which is why health care is always the sleeper issue in any political crisis. Like hunger, like pain, like discomfort, it’s there, sometimes in the background but insistent in its demands. A movement that ignores the body and its needs is not long for this world. That’s what the exponents of fascism secretly want of us, and what only fools would give them.

Pingback: APPE/Felician Roundtable Cancelled | Policy of Truth