“In the literature of complaint and reform, and in the endless reports from distinguished groups identifying a crisis in some element or all of higher education in America, a key defect is often the absence of practical solutions.”

–John V. Lombardi, How Universities Work, p. 31.

In an essay I posted here a few weeks ago, I argued that genocidaires seeking lower-level electoral office should be denied such offices at the ballot box. The argument was framed as a response to Jason Brennan’s account of the ethics of voting, which he describes as “the ethics of voting in political contexts.”(1) Though he doesn’t quite define “political contexts,” it’s obvious enough that he means voting in democratic elections for governmental office, e.g., for U.S. President, for legislative offices, and in some cases for judicial offices, taking U.S. electoral politics as the paradigm.

Close readers of my post might have noticed that in discussing “lower level” offices, I focused primarily on electoral offices, but threw in an example or two of a “lower level office” that wasn’t an electoral office, like university president. University presidents aren’t, in the conventional sense political officials, and aren’t in that sense elected, either. So why bring them up?

As it happens, I regard university presidents as covered by the logic of my argument, along with provosts, deans, executive vice presidents, vice presidents, trustees, and so on. I actually think that faculty, students, and staff are covered by it, too. And though it would require a separate argument dealing with somewhat different issues, I regard outside speakers and recruiters as covered by it as well. Call me “woke” (for all I care), but I regard academic life as a Safe Space from Genocidaires. I don’t think they have any legitimate business on campus, and think they should be declared persona non grata there.

Nicolás de Ovanda, architect of the Encomienda (early 1500s)

The argument I made was that there are character-based conditions not reducible to policy expectations that are sufficient for voting against someone in electoral contexts. If someone is up for electoral office, but guilty of bestial crimes like genocide, a voter ought to veto their candidacy for office, either because their character unfits them for office, or because their actions demand punishment incompatible with holding office. This happens to be true whether the injustices they’ve committed predict unjust behavior in office or not. The specific context I discussed involved high-level officials seeking low-level office, but on reflection it should be clear that the conclusion of the argument applies to anyone seeking any electoral office whatsoever. Genocidaires are unfit for electoral office, full stop.

On further reflection, however, it should also be clear that the logic of my argument applies beyond electoral office to political office more generally, whether electoral or appointed, and from political office to appointments of a public-facing nature more generally. The way I put things in the original post was to say that genocidaires should be removed—purged—from “politics” or “public life,” treating electoral office as one instance of this more general commitment. Since most appointments are in some sense public-facing, the exclusion of someone from “public life” really amounts to their exclusion from gainful employment as such. It amounts to total ostracism, the preferred punishment in ancient Athens, and one that I think we should consider adopting here.

My basic claim is that evil is a veto on being rewarded by others, and that genocide is among the most bestial evils any human being can commit. Once you commit this act, morally speaking, you’re an outcast from the human race, and ought to be treated that way. There are moral limits on what can be done to you, but there are equally stringent limits on what should be done for you. Nothing should be done for you. You should roam the Earth until you die for lack of the assistance to sustain you. People who starve others to death should learn on their own bodies what hunger really means.

Andrew Jackson, architect of the Trail of Tears (1830)

Such people should at the very least be excluded from academic life. The continuities with the electoral case are there, if anyone wants to insist on them. University presidents aren’t elected officials, and don’t literally campaign for their appointments in the way that politicians do, but they go through a quasi-political selection process that resembles an election campaign, and are elected in the analogical sense that constituencies within the university are asked, whether sincerely or not, for their buy-in on a given candidate. Ultimately, the university’s Board of Trustees votes on the decision to hire in a straightforward way.

The considerations that apply throughout the hiring process for university presidents (and others) differ only in ethically trivial details from campaigns for electoral office, resembling them in all morally relevant respects. And so, I conclude, university presidents belong on the list of offices from which genocidaires should be blacklisted. No genocidaire should be voted by any Board of Trustees into the presidency of any university, and no university should tolerate having a genocidaire as president. Or as anything else on campus.

I don’t mean to imply that there are no difficult issues here. The most difficult issue, of course, is what qualifies as a genocide. But “controversy” is not a synonym for “indefinite undecidability” or “epistemic paralysis.” A controversy is an invitation to inquiry, the very thing that academic life claims to be for. Higher education claims to be motivated by the desire for self-knowledge. Asking whether or not your institution facilitates or enables genocide is an obvious instance of that inquiry.

Another difficult issue is proximity: who counts as a genocidaire? How much of a contribution crosses the line, and under what circumstances? This, too, is an invitation to good faith inquiry—meaning, the kind of inquiry that asks a question it genuinely seeks to answer. Unfortunately, higher education is full of people who treat questions as instruments of skeptical quietism or as occasions for pious evasion, rather than authentic inquiry seeking real-world application. That has to change.

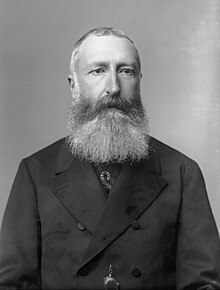

King Leopold II, architect of the genocide in the Congo (1890s)

What’s not disputable is the urgency of the issue. Anyone who reads the news knows that there’s plausibility to the claim that Israel has committed genocide in Palestine, with superabundant American help. Given this, and the results of the 2024 election, there’s no shortage of genocidal “refugees” let loose from the Biden Administration, looking for jobs anywhere they can find them, including academia.(2)

I understand that the issue of Israeli guilt is a highly controversial matter in certain quarters, and have so far written in such a way as to be agnostic about exactly which people I’m looking to exclude from academic life. My primary thesis doesn’t stand or fall on which, but applies to any and all that qualify.

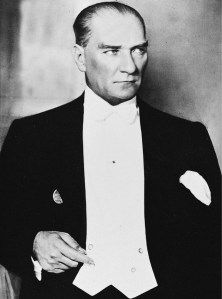

Kemal Ataturk, architect of the second Armenian genocide, 1915-1917

As for Israel and Palestine, I’ll leave things at a bare and semi-neutral minimum. We hear a great deal nowadays about the need for “scholarly,” “rigorous,” and “informed” debate–as contrasted with mere moralism or emotionalism–about Israel. We’re cautioned repeatedly not to accept “Hamas propaganda,” or fall however unwittingly into “anti-Semitic tropes” when it comes to making moral judgment.

Fine. I don’t happen to think that Hamas propaganda is any worse than Israeli propaganda, or that anti-Semitic tropes are worse than any other kind of invidious stereotype, but I’m all for rejecting propaganda and stereotypes. That said, there’s no honest way to conduct an inquiry on this subject without granting the following as possibilities:

- Israel has long been an apartheid state whose existence has long been predicated on ethnic cleansing;

- the Hamas attack of October 7 was a response to the preceding prior aggression, not an initiatory aggression of its own;

- the October 7 attack was in part a justified response to Israeli aggression (though in part not);

- even the most egregiously criminal aspects of the October 7 attacks were morally on par with things that Israel has done for decades, rather than sui generis departures from some prior norm;

- Israel has since October 7th committed genocide (or engaged in a genocide) in Gaza;

- the United States is complicit in Israel’s genocide;

- many of the ubiquitous charges of “anti-Semitism” made by Israel’s apologists are self-conscious attempts at deflection, intended to draw attention away from the preceding possibilities.

A person unable able to grant these possibilities as possibilities is really not capable of engaging in a bona fide inquiry on this subject. Yet most talk about “rigorous inquiry” about Israel/Palestine excludes them from the outset.

Lazar Kagonovich, architect of the Holodomor (1932-33)

Given the preceding, we also have to grant the possibility that many former Biden Administration job-seekers–Harris, Blinken, Sullivan, Austin, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, et al–are glorified war criminals on the run, morally indistinguishable from the likes of, say, Slobodan Milosevic or Radovan Karadzic, and deserving of the same fate.(3) If that’s what they deserve, it’s a mistake to give them university presidencies, chaired faculty positions, 1:1 (or 1:0) teaching loads, and tenure.

When an institution like Harvard effectively blocks condemnations of Zionism as “anti-Semitic,” and blocks ordinary inquiry into genocide as “one sided,” we have to be clear: we’re dealing with bad faith actors. And it would be culpably naïve to evade the fact that such bad faith serves eminently practical ends: it helps get Israel off the hook, and helps purchase its apologists job security that would otherwise be difficult to get.

If that’s the game these people want to play, or give every impression of playing, they can’t complain when their adversaries accept the invitation, but play by their own rules. When an institution of higher education exceeds a certain threshold in violating the norms of academic integrity, it forfeits the moral right to complain about any hard-ball tactics taken by its adversaries. At that point, its adversaries will come to the inevitable and reasonable conclusion: when you’re dealing with frauds of the sort represented by the average university administrator, you’re justified in taking your lessons in negotiation etiquette from the likes of Mario Savio, Ernie Chalmers, and the Weather Underground. You’ve got to party like it’s 1969.

Critics may regard the preceding gambit as excessively “risky” or “inquisitorial.” What if the accusers turn out to be wrong? What if they wrongfully accuse the innocent? What if innocent people needlessly lose their jobs as a result? What if the spirit of recrimination I recommend here ends up creating the equivalent of an Inquisition, or ends up backfiring, and harming the accusers themselves? All those things could happen (some probably will happen), and safeguards have to be adopted to prevent them.

But critics of this sort too often conflate caveats with counsels of despair. Either we have accountability for criminality, or we don’t. Where there’s accountability, there’s the possibility of error or excess. That’s regrettable, but impunity isn’t costless or without risk, either. The alternative such critics envision as “safe” is a free ride for some of the most bestial, mendacious criminals on the planet. There’s no clear calculus by which academic genocidocracy is more obviously acceptable than the “disruptions” of even the most disruptive campus “inquisition.”

Martin Heidegger, Nazi ideologist, Rector of the University of Freiburg, later given emeritus status, 1933-1945, emeritus status awarded 1949

Some questions are worth asking these would-be critics in return. What if our colleges and universities come to be inhabited and governed by genocidaires? What if these genocidaires use the university to indoctrinate future generations in their brutalities and lies? What if, in tolerating them, we not only normalize life under an academic genocidocracy, but normalize the idea of university complicity in future genocides? These questions mostly appear to have gone unasked: where “institutional neutrality” is the summum bonum, hand-wringing becomes the crown of the virtues.

So while they have a point, these critics need to get real. How many of them, after all, think that academic institutions should stop asking job applicants whether they have a criminal record–as they do for all jobs on campus, from dining services to the presidential suite?(4) How many think it self-evident that felons convicted of violent crimes should be hired at universities with no further scrutiny over the context or circumstances of their crimes? It makes no sense to exclude shoplifters and drunk drivers from on-campus employment while inviting war criminals to become chaired faculty, deans, provosts, and presidents. Yet that’s the “logic” we’re almost universally expected to accept as normal.

Pol Pot, architect of the Cambodian genocide, 1975-1979

“If justice perishes,” Kant wrote, “there is no longer any value in men’s living on the earth.”(5) He was exaggerating, but the specifically academic version of his thesis has a real plausibility about it. If justice were trampled on with impunity in higher education–if academia were willingly to appease mass murderers and normalize mass murder–the rationale of the institution would in fact be put in question.(6)

The somewhat cynical truth is that it’s very unlikely that any conflict over genocidaire job seekers is going to lead to any real dislocation in American higher education. Evasive, delusional acquiescence is the more likely outcome, along with a fair share of defamatory punching down, and deportations and arrests of “Hamas sympathizers.” It’s pretty obvious that we’re playing with loaded dice nowadays. But suppose there was the academic equivalent of a civil war over genocide, something on par with tumult of the 60s (or less “virulently,” the 80s). Would it be worth it?

Radovan Karadzic, poet, psychiatrist, politician, genocidaire (1995)

I think so. If academia were to be inhabited and governed by genocidaires and their apologists tout court, we should be glad to see the institution shaken up, and in the worst case scenario–a wholesale take-over by genocidaires and their fellow-travelers–even destroyed. Its destruction would in that case be collateral damage of the crimes committed by the guilty, the crimes that they and their partisans had worked so hard to conceal, minimize, excuse, and evade. In that case, the wholesale destruction of academia would mean not that justice had perished from the Earth, but that it had at long last had its say. It would be a bittersweet denouement for an institution with a problematically checkered past, but an entirely deserved one, and one for which blame would fall entirely on the guilty, where it belongs. Not a happy ending, by any means, but no cause for regret.

Endnotes

- Brennan: “This is a book on voting ethics. In particular, it concerns the ethics of voting in political contexts. (It is not about voting for MLB All-Stars of American Idol contestants.)” (Jason Brennan, The Ethics of Voting, p. 1). As I make clear in the post, voting in political contexts and voting in trivial contexts is far from exhaustive of the relevant possibilities. Brennan’s formulation ignores voting in work-related contexts, among many others. Indeed, voting in work-related contexts is just an instance of voting in contexts of voluntary association, where the alternative to voting is, for all practical purposes, operating by a set of top-down commands. In any case where we have reason to avoid top-down commands, we have reasons to vote; in any case where we have reason to vote, and do vote, we have the need for an ethics of voting. So Brennan’s rationale for restricting discussion to “political contexts” involves a red herring; the topic has broader scope than he suggests.

- I don’t mean to be ignoring Trump appointees, of course. “Let’s not mince words here. The people of Gaza are collectively guilty for invading Israel, murdering, raping and kidnapping Israelis and holding them hostage….The actions of the Gazan people prove they need detoxifying education before the reconstruction should even be able to begin. They are fundamentally evil, and they must pay a price for their action.” That’s Martin Oliner, Trump-appointed board member of the US Holocaust Memorial Council in a Feb. 1 editorial in The Jerusalem Post (“Let Donald Trump Make Gaza Great Again“). Oliner’s claim here is morally on par with anything advocated by the Khmer Rouge, and deserves the same treatment. To belabor the obvious, my argument applies to appointees to public councils in much the way it does to academic positions: people like Oliner should be excluded from such positions or if possible, fired; where appropriate, such people should be ostracized or even prosecuted. And we can’t close the door on the possibility that some such individuals are legitimate candidates for assassination (a point I make very generally for purposes of theoretical discussion, not as an actionable prescription regarding any particular individual). Julius Streicher was, after all, executed, for incitement; prima facie, it would have been justifiable to assassinate him if he couldn’t have been captured. Arguably, the same logic applies to contemporary genocide-inciters. To belabor another obvious truth: it was Israel that invaded Gaza in June 1967, has militarily occupied it since, and has blockaded it since 2007, not the other way around. If there can be collective guilt for conquest, murder, sexual assault, and kidnapping, Israel is the more obvious candidate for it than Gaza. It would take a separate post to discuss in detail how organizations like the US Holocaust Memorial Council should be dealt with, but the general point should be clear enough. On the topic of incitement (with specific reference to the Rwandan genocide), see Richard A. Wilson, “Inciting Genocide with Words,” Michigan Journal of International Law 36:2 (2015).

- Essential reading on this topic is Raz Segal’s “Genocide Denial in Holocaust Studies,” Jacobin, January 27, 2025. See also Amos Goldberg and Daniel Blatman, “There’s No Auschwitz in Gaza. But It’s Still Genocide,” Ha’aretz, Jan. 30, 2025; Pankaj Mishra, “Israel and the Delusions of Germany’s ‘Memory Culture,'” The Guardian, Jan. 30, 2025; Jake Sonnenberg, “The Return of Genocide Denial,” Jacobin, Jan. 31, 2025; Jonathan Cook, “How the West Hides Its Gaza Genocide Guilt Behind Holocaust Day Remembrances,” Middle East Eye, Jan. 31, 2025; Chris Hedges, “The Western Way of Genocide,” The Chris Hedges Report, Feb. 1, 2025; and Mari Cohen, “Can Genocide Studies Survive a Genocide in Gaza?” Jewish Currents, Fall/Winter 2024. This is a small sample of a much bigger literature, drawn almost entirely from items published online in a single week (Jan. 25-Feb. 1, 2025). As Jonathan Cook points out, it’s notable that Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Doctors without Borders have all issued reports agreeing on the verdict of genocide. A similar judgment has been reached by the University Network for Human Rights, as well as the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Palestine. Though B’Tselem has shied away from the use of “genocide,” it has leveled a charge of ethnic cleansing, and the serial commission of war crimes. Most of the evidence mentioned here has gone unacknowledged and uncontested in mainstream discussion, but the accusation of genocide is difficult to dismiss.

- An example of academic double standards from my own academic experience is instructive. I taught for thirteen years at Felician University in northern New Jersey. When the assistant resident director of the university was charged with sexual assault, and it was discovered that he had previously been arrested for armed robbery, he was terminated before he was tried or convicted for either crime. An arrest record was deemed sufficient for termination. Three years later, the university hired, as president, a former naval admiral who had been found unlawfully to have influenced the proceedings of a rape trial; the finding of unlawful influence was made in a formal judicial proceeding by the United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces. The admiral’s retirement from the Navy and acceptance of the Felician presidency–offered in the full knowledge of the court’s finding–enabled him to escape a court martial. In this case, a formal finding of guilt was regarded, by some of the same individuals who had terminated the assistant resident director, to be compatible with hiring someone as president of the university. The double standards involved here should be transparent. Yet a university that hired genocidaires while excluding, say, drug dealers or thieves, would be guilty of a form of corruption that makes Felician’s seem trivial by comparison.

- Immanuel Kant, The Metaphysics of Morals, I.II.1.E, Ak. 332.

- I raised this question more than two decades ago about Princeton’s study abroad program in China: if a program requires the abdication of academic freedom, is it worth having?

Thanks to Michael Young for helpful comments prior to posting. Thanks also to Susan Gordon for bibliographical suggestions, and to Kate Herrick and Hilary Persky for helpful discussion.

Pingback: Let Them Eat One Another | Policy of Truth

Pingback: Complicity, Neutrality, Atrocity (3/5) | Policy of Truth