I wanted to note the passing of John Wilmerding (1938-2024), for many years the Christopher Binyon Sarofim Professor of American Art at Princeton University. He died on June 6 of this year at the age of 86.

I didn’t really know Wilmerding at all–never met him, never really took a class with him. He was the guest lecturer for the week-long section on American art in my college-level art history class, Art 100, “An Introduction to the History of Art”–the closest to physical contact I ever got. But more than anyone, I owe Wilmerding credit for my decades’- long love affair with American art, and in particular, American landscape and maritime painting of the mid- to late-nineteenth century.

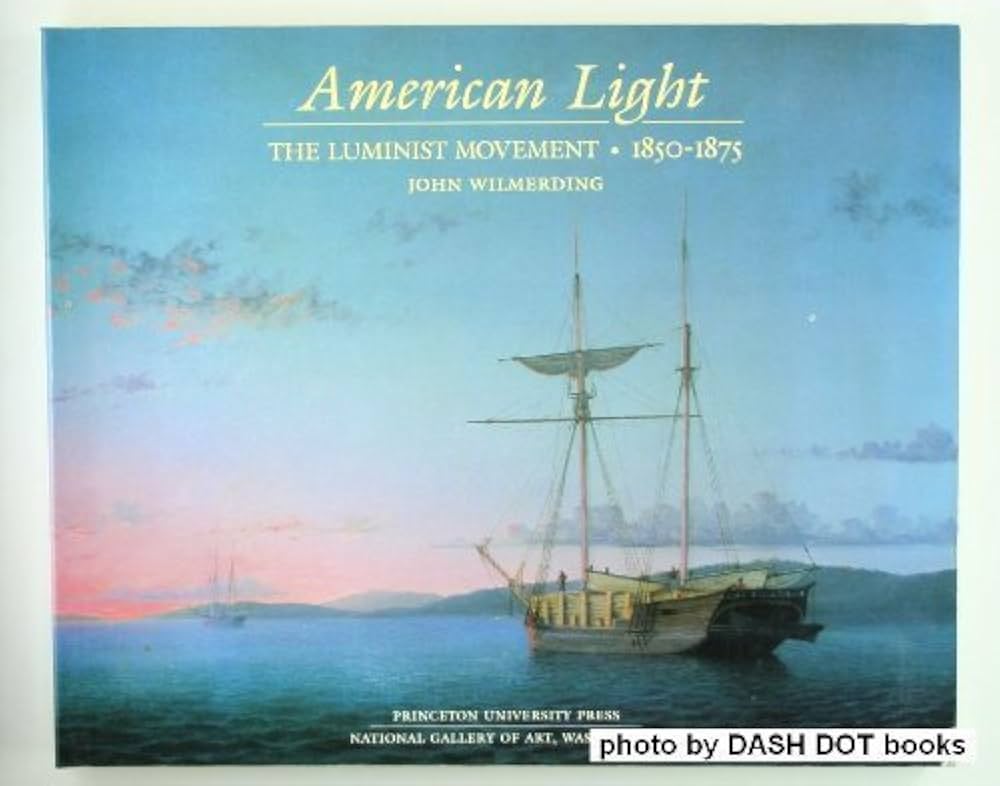

I first encountered “high” American art through an edited collection of Wilmerding’s that I found at a local book fair, American Light: The Luminist Movement, 1850-1875. I bought my copy in 1990, but didn’t finish it until more than a decade later. The illustrations distracted me from the text. The text distracted me from the illustrations. The book distracted me from the world.

It’s telling that if you Google the phrase “American Light,” what comes up is not Wilmerding’s book but a bunch of advertisements for businesses that offer a “wide range of lighting solutions for your residential, commercial, and specialty lighting needs.” The contrast is apt: Luminist art aestheticizes the sublimity and stillness found in nature, often tempered by an uneasy sense of the trade-off between natural beauty and the unaesthetic imperatives of material progress. There are, you might say, two sorts of “American light”: one the theophanic atmospherics of luminist and tonalist painting, the other an eminently practical solution to the problem of darkness. We owe the latter to Thomas Edison, and the former to the painters Wilmerding chronicled, analyzed, and valorized. Both in some sense bring the world to light. But each somehow stands in tension with the other.

I eventually made my way through many but not all of Wilmerding’s books, and made my share of pilgrimages from Mount Desert to the National Gallery in search of the shrines and altars to the paintbrush gods he chronicled. It sometimes seemed a trivial or incongruous pursuit in a world of war, massacre, famine, and plague, but I’ve never been fully convinced that it is. As the light bulb is the solution to one kind of darkness, so the contemplation of sublime light on canvas seems the solution to another.

It’s tempting in this respect to think of luminist painting–or landscape painting as such, maybe art as such–as a respite from a cruel and ugly world, except that the works of Frederick Church, George Inness, Fitz Hugh Lane and the rest are as much a part of the world as any of its darkest moral depths. So art is as much a respite from the world as a reminder of it. But an odd sort of reminder: It’s somehow disturbing to prefer a painting to a photograph of the painted object or even the object itself. How is it that “The Artist’s Mount Desert” beats Mount Desert? But it often does. I encountered Plato’s argument against mimetic art around the time I encountered Wilmerding’s American Light, and the question of “aesthetic escapism” has tormented me ever since.

It’s not all torment, of course. Wilmerding’s scholarship reflected, in his words, the “aspiration to search the luminist horizons afresh, and to view them as panoramically and precisely as the style itself…” (“Introduction,” American Light, p. 19). He succeeded, and then some. If it’s problematic to prefer paintings to “the world,” perhaps there’s compensation in what one brings back to the world after the visit “abroad.” The recurring image in American landscape and maritime art is the sheer stillness of land, sea, and sky against the light on a distant horizon. If “American light” means anything, that’s what it means.

Sometimes, the light you see on the horizon is the only compass you have out of disaster. Sometimes it leads to a physical location, sometimes to an inner one. In either case, at its best, it leads you to where you need to go. I’m grateful to Wilmerding for helping me find my way there, and hopeful that the light he brought to light will endure.

“I encountered Plato’s argument against mimetic art around the time I encountered American Light, and the question has tormented me ever since.”

Here Aristotle differs from Plato: “poetry is more philosophical and more serious than history, for what it conveys is more universal.”

LikeLike

I find the whole topic unsettling, particularly in the case of painting. I don’t quite get Aristotle’s argument even in the case he has in mind. Harder still to apply it to a case he couldn’t have had in mind.

I read something the other day about Bonaventure’s conception of memory that seemed apt. I haven’t read Bonaventure in thirty years, but apparently, he says something to the effect that memory is less a “snapshot” of a past event than the conferring of a sense of timelessness onto a particularly salient event that gives it an intimation of immortality. Predictably, he says this phenomenon is a gift from God meant to remind us of our immortal souls.

It seems to me that great paintings have that Bonaventurian quality about them: they don’t just give an accurate depiction of a place in the way that a photo does, but lend it a personalized sense of timelessness akin to immortality.

The puzzle for me is that while I find that an attractive thought, I don’t believe in immortality, so I need a different interpretation of it. Unfortunately, I not only don’t have one, but don’t have time to work it out. The irony.

LikeLike