Having finished with Gerald Gaus’s The Tyranny of the Ideal, our MTSP Philosophy Discussion Group is now back to reading philosophy of law, working our way through Lon Fuller’s The Morality of Law (1964/1969). Fuller’s book is Roderick Long’s choice, part of a sequence of books on philosophy of law we’re reading at his suggestion, starting with H.L.A. Hart, passing through Fuller, eventually en route to the work of Ronald Dworkin.

Having just read the first chapter of Fuller (and for the first time), I have to say that I find Fuller a refreshingly clear and engaging writer, much easier to read than, say, Gaus, Scanlon, or Hart. But clear as Fuller is, I don’t find his arguments in this first chapter sound. In this post, I want to offer a quick-and-dirty (but still, I think, effective) criticism of just one point he makes in the chapter, namely, his supposed distinction between “the morality of duty” and the “morality of aspiration.”

Early on in Chapter 1, Fuller distinguishes between what he calls “two moralities,” the “morality of duty” and “the morality of aspiration.” The distinction between them is meant to be exclusive, and is meant to bear the weight of much of his subsequent argument.

The morality as aspiration is a morality of moral ideals divorced from a sense of imperatives or obligations; it’s what excellence requires us of us, without being literally demanded of us.

The morality of aspiration is most plainly exemplified in Greek philosophy. It is the morality of the Good Life, of excellence, of philosophy. In a morality of aspiration, there may be overtones of a notion approaching that of duty. But these overtones are usually muted, as they are in Plato and Aristotle. Those thinkers recognized, of course, that a man might rightly fail to realize his fullest capabilities. As a citizen or as an official, he might be found wanting. But in such a case he was condemned for failure, not for being recreant to duty; for shortcoming, not for wrongdoing. Generally with the Greeks instead of ideas of right and wrong, we have rather the conception of proper and fitting conduct, such beseems a human being functioning as his best (Fuller, Morality of Law, p. 5).

The morality of duty, by contrast, is a set of moral minima expressed as imperative rules, themselves understood as binding obligations or duty. We either must do something or must not. If we satisfy the imperative, we act rightly; if not, we act wrongly.

Where the morality of aspiration starts at the top of human achievement, the morality of duty starts at the bottom. It lays down the basic rules without which an ordered society is impossible, or without which an ordered society directed toward certain specific goals must fall short of its mark. It is the morality of the Old Testament or Ten Commandments. It speaks in terms of ‘thou shalt,’ and less frequently, ‘thou shalt not.’ It does not condemn men for failing to embrace opportunities for the fullest realization of their powers. Instead, it condemns them for failing to respect the basic requirements of social living (Fuller, Morality of Law, pp. 5-6)

There are textual quibbles to be had here over Fuller’s readings of Plato and Aristotle, and of the Hebrew Bible; I think he’s misread all of the above. But set that aside. My basic quarrel here is conceptual. The distinction in question is either unclear or a false dichotomy. Let me pursue the latter criticism. Put briefly, my criticism is this: The distinction between the two moralities is supposed to be exclusive, but in fact isn’t. In one sense, the morality of duty requires the morality of aspiration; in another sense, the morality of aspiration requires the morality of duty. I don’t just mean this in an instrumental sense, e.g., that the pursuit of aspirations requires the institutionalization of basic duties, and that the pursuit of basic duties is enhanced by the pursuit of ideals. That’s true, but not my point. I mean that each ethic is embedded in the other in ways that make it impossible to draw the kind of distinction Fuller wants to draw.

Fuller writes of the ethic of duty as though the duties involved in it were so minimal that no great moral effort or aspiration were involved in satisifying them. This has a certain plausibility if we focus very narrowly on rules like “Do not commit murder.” This rule is so basic and minimal in its demands that little or no effort is required of an ordinary person to satisfy it. We satisfy it essentially by default. But suppose we conjoin the proscription against murder with a different but related rule from the same moral vicinity: “Do not act so as to produce wrongful death.” This rule certainly has the form that Fuller ascribes to the ethic of duty. It doesn’t belong to what he calls the ethic of aspiration. And it’s a duty, not an idealized non-obligatory aspiration.

Yet satisfying it is far from easy. It is highly unlikely that the average person does everything required, every waking moment of every day, to satisfy it. To satisfy it, a person would have to act so as to bring the probability of causing wrongful death as close to zero as it was humanly possible to go. Only the moral athletes among us are that careful. Think of driving: how many people drive a car with the care that airline pilots take when they fly a plane? How many people maintain their cars with the care that airline crews or surgical technicians take with airplanes or surgical equipment? Almost no one. If such people existed, and acted in this way every day, every moment, without fail, they would exemplify a moral ideal almost never exemplified in human life. They would be the saints of the quotidian. But it seems to me such people satisfy Fuller’s criteria for the morality of aspiration. They are ideal exemplars with respect to adherence to the basic norms of ordinary life.

Now imagine that we conjoin one more rule to the preceding two: “Do not permit yourself to be complicit in murder or wrongful death.” This rule is obviously related by subject matter to the other two. It’s obviously a duty, and obviously part of everyday, quotidian life. If we take it to be a moral duty, then it belongs to the ethic of duty. But if we look to the arduousness of its demands, it seems to belong to the morality of aspiration. To satisfy this duty, you would have to do everything in your power to distance yourself from every policy in which you were in some sense complicit, corporate or governmental, that was such as to have some tendency wrongfully to kill people or to murder them. The dual nature of this duty–partly duty, party aspiration–strikes me as a counter-example to Fuller’s distinction. This is a perfectly recognizable duty. Many people regard it as basic to morality. It’s a duty, not an optional opportunity to excellence. But it easily lends itself to an inflationary, aspirational interpretation: it would take huge efforts to begin to satisfy the inflationary version of the duty. On that interpretation, it’s anything but “minimal” in its requirements. The lesson seems to be that a “minimal” rule can be re-conceived to have maximal demands while remaining a duty taking the form of a rule.

Take a more prosaic rule: “Don’t lie.” It’s a well known fact that this rule is, as stated, too demanding to be reasonable. So imagine that it’s qualified however you like. Now take the qualified version of the rule, “Don’t lie, except in cases of type X,” where type X is some knowable, determinate, reasonable class of exceptions. Is following this latter, qualified rule a matter of duty or of aspiration? In one sense, it’s clearly a matter of duty. But in another sense, it’s just as easily a matter of aspiration. Almost no one follows any rule of any stringency that demands that they refrain from lying. We live in a milieu that practically demands lying. It’s difficult to go through an eight hour workday in an American business context without telling a series of lies. The idea of telling no lies (even within the context of some qualified rule) would strike many if not most corporate business types as utterly preposterous. To refrain from lying in a context like this is not the “minimal” achievement Fuller takes it to be. It’s about as rare an achievement as Plato’s dream of the philosophers becoming the kings of the city-state. It’s an idealized aspiration almost never achieved in the real world, not a moral minimum we can all take for granted as the “floor” of a decent society.*

Take the rule that we ought to keep the promises we make. The same point applies here. It applies even to ordinary promises of the kind that friends make with one another. If I tell you that I’ll meet you at the coffee shop at 3, and I show up at 3:05, I’ve broken my promise. Yet we rarely hold people to this degree of assiduity. It’s taken for granted that promises are meant to be kept in a rough-and-ready way, and that we’re to be easygoing and tolerant of those “recreant to duty.” Yet breaking a promise is recreant to duty, even if the duty is a matter of punctuality down to the minute.

Now suppose that we introduce promises that arise through contractual “bargaining” in contexts of asymmetric bargaining power, e.g., of employer and employee. In these cases, the employee agrees to “serve at the pleasure” of the employer. Suppose that the employer demands that the employee perform some ridiculously arduous (but physically possible) task in ridiculously limited (but physically possible) time. Suppose this expectation arises not just once or twice, but every working hour of every day, eight hours a day, five or six hours a week–plus as many weekends as the boss demands. Satisfaction of an “ordinary” promise under these conditions would require almost superhuman effort, determination, patience, and endurance.

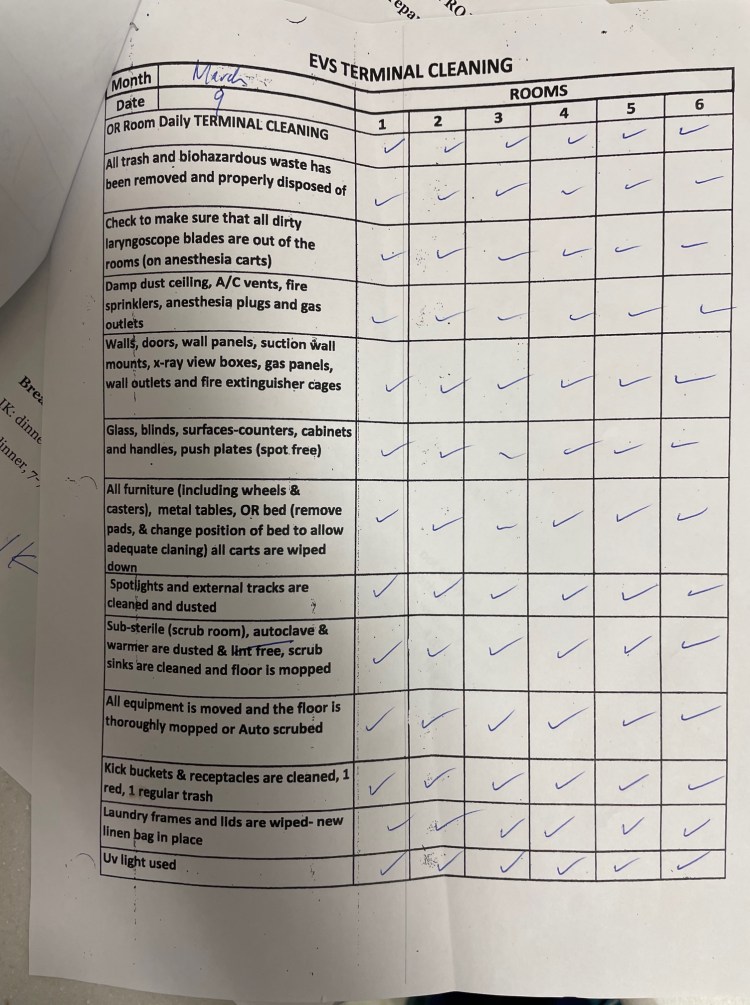

To give you a concrete sense of what I mean, I’ve reproduced two “project sheets” nearby from my days of working as an operating room janitor. I happen to remember this particular day, March 9th, because it was the day before I learned that my wife died by suicide. I got news of my wife’s death on March 10; my managers agreed that I was too distraught to work that day. But March 11, it was agreed, I was to return to work and resume my ordinary work routine–the routine I had left off on March 9 (and which the other person on my shift, IS, had had to do on his own on March 10). The untimely death of one’s wife was not regarded as a particularly good excuse for taking time off from work in the OR. People, it was thought, die. Moping over their deaths won’t bring them back, and more importantly, won’t bring the OR any revenue. Better to work off one’s grief than sit around crying over spilled blood. In fact, better to clean spilled blood than cry about it.

The checklist was a non-exhaustive summary of the work that those of us on the evening shift had “promised” to do within our eight hour shift; in fact, there were, in addition, unenumerated duties nowhere on the sheet. (The first item on the sheet–“Terminal Cleaning”–subsumed dozens of discrete, time-consuming, labor-intensive activities.) The typed sheet, written pro bono while we were nominally off duty, was our daily confession of failure. Every claim on it enumerating what was not done–“kitchen not mopped”–was a signed confession of a broken promise on our part. You can see our guilty initials scrawled at the bottom of the page, mine more conspicuous than my colleague’s, but both there.

Could we, physically, have done absolutely everything asked of us, every night, without fail, keeping our rate of errors as close to 0 as possible? I don’t know. Our duties were never defined in terms of what was humanly possible. But we could in principle have re-conceived our duties and our efforts in terms of some ideal–call it an OR janitor’s equivalent of an Olympic ideal–of what was possible to human beings qua human working themselves to exhaustion every night for $14 an hour. We didn’t do this. Did we fail to live up to our duty? Or did we fail to live up to an idealized aspiration to human excellence? I would say that we did both: we failed to do our plain duty, and we failed to live up to an idealized aspiration to human excellence; living up to that Janitorial-Olympic ideal is just what our plain duty required. Contrary to Fuller, there’s no way to prise these two things apart in this case, or in cases like it.

What this suggests to me is that the morality of aspiration can plausibly be seen as being internal to the morality of duty. If we formulate a duty as a duty, we can imagine various degrees of adherence to it, and various interpretations of its stringency. Maximal adherence to the most stringent interpretation of even an ordinary rule becomes an idealized aspiration on par with anything that Plato and Aristotle regarded as human excellence.

If you doubt this, try living a fully Islamic lifestyle for Ramadan, refraining from food, drink, and sex from dawn until dusk, saying all five prayers, including fajr, before dawn, refraining from alcohol, and so on. These rules are conceived of as social “minima” in an Islamic milieu. Satisfaction of every duty, in every particular, is regarded as obligatory of every adult. Yet actually adhering to every single demand remains an aspirational feat. Set Ramadan aside: simply imagine waking up for the pre-dawn Islamic prayer every single day of your adult life without exception–never sleeping in or skipping the prayer for any reason whatsoever, short of serious medical danger to your physical health–and then saying all four of the other prayers on time, every day without exception.

Here are tomorrow’s prayer times for Princeton, New Jersey:

Fajr: between 4:44 and 6:06 am

Zuhr: 1:04 pm

Asr: 4:55 pm

Maghrib: 8:01 pm

Isha: 9:25 pm

Performing each prayer, on time, every day, according to the correct ritual procedure, and in a state of ritual cleanliness, is, according to Islam, a duty incumbent on every believer. But it seems difficult to deny that perfect adherence to this duty involves an ethic of aspiration in Fuller’s sense.

Coming the other way around, it seems to me obvious that one can conceive an injunction to satisfy an aspirational moral ideal as a duty. Kant’s conception of duties to oneself seems a perfect example of this (as does Ross’s prima facie duty of self-improvement as described in The Right and the Good). The Randian Objectivist conception of virtue is similar. The Randian virtue of integrity demands, as obligatory, that a person live up to her ideals; the Randian virtue of pride demands, as obligatory, that she have aspirationally high ideals. The conjunction of the two, and the obligatory form they’re given, flout Fuller’s distinction between an “ethics of duty” and an “ethics of aspiration.” Integrity + pride are obligatory, hence duties, but aspirational, hence part of the ethic of aspiration. In general, if I have a duty to perfect myself, then that duty is both a duty and an aspiration on par with the aspirations Fuller describes as “aspirations.” The distinction ceases to apply.

I conclude that Fuller’s distinction is either unclear or a false dichotomy, more likely the latter. What implications this has for his theory, I don’t know.

*The topic is a staple of textbooks of business ethics, and an issue familiar to anyone who’s worked in a corporate setting. See Joseph Heath, “Business Ethics and Moral Motivation: A Criminological Perspective,” and Albert Z. Carr, “Is Business Bluffing Ethical?” both reprinted in Hoffman, Frederick, and Schwartz, Business Ethics: Readings and Cases in Corporate Morality, Fifth Ed. (2014).

As a layperson, I can’t see the point of the distinction. You ought not to murder, you ought to put in a good day’s work. These commandments are both contingent on circumstance. That’s it, no?

LikeLike

The point of the distinction has to do with law. Law clearly bears some relation to morality. It’s not a literally amoral set of rules. Legal scholars in the English-speaking tradition (like Fuller) have wanted to keep the relation between morality and law as minimal as possible. If law is going to be informed by morality, it should presuppose as modest, unambitious, and prosaic a conception of morality as possible–e.g., don’t lie, don’t steal, don’t murder, keep your promises, etc. No more than that.

But not all historical conceptions of morality have taken that simplistic form. Some moralities have pulled God into the equation. Some have pulled some fancy metaphysics into the equation. Some have saddled us with very ambitious aspirations to virtue, perfection, and excellence. Etc. Fuller wants to chop all of those immodest, ambitious, exotic things out of morality, for fear that if you let them in, the relationship between law and morality becomes unmanageably complex and difficult. He wants to escape the old religious conception of law associated with the Catholic Church while also avoiding a descent into the view that law is an amoral instrument of state power. That’s the rationale for dividing morality into two halves, and pushing one half out of the way.

The distinction he uses to do that was very common in mid-twentieth century Anglo-American philosophy. “Let’s isolate a set of simple duties with which everyone is familiar, and relegate high-minded ideals of The Good Life to the side, so we don’t need to think about all that or integrate it into our theory.” I don’t think the move really works. Ultimately, no duty is “simple.” The simplest duty becomes complex when you ask how it relates to other considerations. It only looks simple if you stare directly at it and forget everything else. This is what Fuller seems to me to be ignoring.

Take a simple duty: “We have a duty to recycle.” OK, fine. But how far does it go? We can’t recycle time. So how much time do I have to spend on preparing things for recycling? Suddenly, a duty that looked simple turns out not to be.

Every dispute in my current household revolves around this “simple” duty. The explanation for the dispute is that the disputants hold different ideals of the world. My housemate, the recycling fanatic, is basically a radical environmentalist. For her, recycling is not just a practical activity but a religious ritual that defies any cost-benefit analysis. I’m a humanist. I don’t care about The Environment except insofar as it affects people. So from my perspective, recycling needs to be subjected to a cost-benefit analysis. And if it fails that analysis, we stop making such a big deal of it and throw things out.

Fuller wants to treat this disagreement as merely a narrow one about recycling. But I think it’s a disagreement about bigger things. It’s a disagreement about what is of ultimate importance in the first place–The Environment, or human well-being? Ms Recycling says the first. I say the second. The disagreement about the duty to recycle reflects a duty about larger ideals and aspirations. It can’t be understood by focusing exclusively on recycling and forgetting the larger picture.

Tomorrow, I’m attending a nurse’s strike at a nearby hospital. The strike is about wages and staffing: the nurses want better conditions. It is tempting to think that what divides the nurses from management is just dollars and cents: the nurses want more, management wants to give them less. Period. But that’s myopic. The larger issue is about the nature of health care itself: One side wants health care to be about the provision of health. The other side wants it to be about generation of revenue. Those are fundamentally different ideals. You can’t detach the nurses’ demands from that larger context.

I find it interesting that Fuller’s attempt to simplify the world strikes a non-philosopher as difficult to understand. I don’t find it difficult to understand; I find it unsuccessful. But perhaps these are two ways of saying the same thing. It’s a false distinction. I see the point of it because I’ve been trained to. You don’t because you haven’t. But either way, we agree–it’s a false distinction.

LikeLike

The last time I taught Philosophy of Law I gave my students notes on Fuller. Here are the notes on chapter 1:

Lon Fuller’s Law and Morality, ch. 1

Lon Fuller (1902-1978) was a law professor at Harvard, and a strong opponent of legal positivism. But his own position, while a kind of legal naturalism, is not quite the same as that of Socrates or Cicero or Aquinas or Spooner or MLK Jr.

p. 3: “Die Sünde ist ein Versinken in das Nichts” means “Sin is a sinking into nothingness.”

“Die Sünde ist ein Versinken in das Bodenlose” means “Sin is a sinking into the bottomless.”

p. 5: Fuller’s distinction between a morality of duty and a morality of aspiration seems to combine three ideas that he may not fully realise are distinct:

To see that these are not all the same idea, just consider Aquinas. Aquinas regards the portion of natural law that is necessary for social order as a subset of the totality of natural law. But for Aquinas all of natural law is a matter of duties and musts. And while only the part of the natural law necessary for social order is a proper subject of human law, all of it is the proper subject of law in a broader sense.

As for the ancient Greeks, Protagoras (at least as he is presented in Plato’s dialogue of the same name) comes closest to accepting a distinction like Fuller’s, since he argues for the existence of a bare moral minimum that is needed for social order (which nearly everyone is an adequate expert at, as at their native language, since otherwise social order would be less stable than it is), versus a richer morality that goes beyond that (and at which only a few are experts, himself being one of them); but the line of Greek ethicists from Socrates onward through Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics reject Protagoras’s approach, on the grounds that he has too impoverished a conception of true social order; assuming we’ve achieved social order merely because not everybody is stabbing everybody else in the back nonstop is setting the bar too low. So, the Socratic-Platonic-Aristotelean-Stoic viewpoint, as I see it, is not so much a morality of aspiration as it is one that denies the whole distinction between a morality of aspiration and a morality of duty.

In a footnote Fuller apparently endorses J. Walter Jones’ claims that the ancient Greeks “never worked out anything resembling the modern notion of a legal right.” This was a common view at the time Hart was writing, but it is widely challenged nowadays (see e.g., the work of Fred Miller – or, for the mediævals, the work of A. S. McGrade).

(Spooner, by the way, seems to be an example of the view Fuller criticises according to which any wrong actions that aren’t appropriate to forbid must not be harms against others; see his Vices Are Not Crimes.)

p. 6: I don’t think Fuller gets Adam Smith right either. He makes it seem as though Smith’s grammar/style analogy will map neatly onto his own duty/aspiration distinction. He does note in a footnote that Smith himself describes it instead as a distinction between justice and the other virtues, but Fuller doesn’t think this makes too much difference. But Smith is quite consciously emulating the Socratic tradition, which makes it hard to read a duty/aspiration distinction into him. His grammar/style analogy is meant to express how far the application of a given virtue depends on training and good judgment, not on how much it is an ought or a must. Also, Smith definitely did not think that the content of justice was determined by what’s needed for social order; on the contrary, he said that we resort to defending the virtues (including justice) by appeal to their social consequences only when we are faced with scoundrels who do not recognise the value of virtue for its own sake. No utilitarian he. (An example of a moral theorist who is overall very similar to Smith, but who does treat justice as differing from the other virtues in virtue of being a contrivance for beneficial social consequences, is David Hume.)

p. 9: Further grumping: Fuller suggests that because moral perfection cannot be commanded, it has no relevance to the law, and that therefore adherents to a morality of aspiration cannot really express their values in legislation. But thinkers like Plato and Aristotle, who count as aspiration-moralists for Fuller, took moral perfection to be relevant to law, not as something to be commanded directly, but rather as something to be aimed at by a coercive system of moral education. Can Fuller really have forgotten Plato’s Republic?

pp. 18-19: Maybe I’m just hopelessly Aristotelean, but the argument Fuller attributes to Aquinas here (I think Aquinas in the cited passage is actually saying something different, but I also think the argument he’s discussing can be found in Aristotle) that Fuller finds “curious” and “paradoxical” just seems like common sense to me. Maybe I’ll talk about this in class.

I do like what he says about the Aristotelean middle way at the top of p. 19.

p. 21: Fuller says that his qualification of the Golden Rule here is no distortion of its intent. But it certainly seems to be a distortion of the intent of the version in the New Testament (of course that is not the only version), since shortly before introducing the Golden Rule (Matt. 7:12), Jesus says: “Resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also. And if any man will sue thee at the law, and take away thy coat, let him have thy cloak also. … Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you ….” (Matt. 5:39-44)

p. 24: As we’ll see later, treating “capitalism” and the “free market” as synonymous is controversial.

p. 26: Marx’s views on the division of labour are complicated; I don’t think it’s accurate to describe him as having an “antipathy to the very notion.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

I agree with all of that, though of course, I was only focused on (5b).

I’ve never taught this material before. How do your students react to the distinction between an “ethics of duty” and an “ethics of aspiration”? The distinction seems intuitive to anyone who’s read a lot of mid-twentieth century Anglophone moral philosophy, but I wonder if it just comes across as unmotivated and unintelligible to everyone else. Which is interesting, in a way, because Fuller seems to think it should be intuitive to anyone.

I’m half tempted to go around my office, describe the distinction, and ask people what they think about it, but I think I would just be accused of wasting valuable time, and told to back to work–leaving sadly unanswered whether the task of hitting my “OKRs” is a matter of duty or of aspiration. (OKRs: Objectives and Key Results, i.e., productivity metrics).

LikeLike

Is “rocking the world” a duty or an aspiration?

Answer: if you’re in the C suite, it’s an aspiration. If you’re lower down in the organization chart, it’s a duty. I don’t think this is what Fuller had in mind, however.

LikeLike

“How do your students react to the distinction between an ‘ethics of duty’ and an ‘ethics of aspiration’? The distinction seems intuitive to anyone who’s read a lot of mid-twentieth century Anglophone moral philosophy, but I wonder if it just comes across as unmotivated and unintelligible to everyone else.”

As I recall, some of them went for it and some didn’t. In my experience something like the distinction is pretty common among Christians who want to distinguish between those Biblical commands that they regard as binding and those (e.g., the turn-the-other-cheek, sell-everything-you-own-and-give-the-proceeds-to-the-poor stuff) that they kind of want to postpone.

There’s a similar distinction in a number of Indian religions (e.g. Buddhism, Jainism, Hinduism), where advanced practitioners take on the full load (vegetarianism, pacifism, poverty, etc.) while lay followers take on a lighter version of the load, with the expectation that they will tackle a more burdensome version either in old age or in a future incarnation.

LikeLike

Incidentally, most of what I like in Fuller’s book doesn’t turn on the aspiration/duty stuff much at all.

LikeLike

I previously neglected to include excerpts from my Philosophy of Law course handouts for chapter 3 of Fuller here, mainly because on my course website I had some of the chapters mislabeled. But here they are, along with a rather more modest bounty of notes on ch. 4:

Fuller’s Law and Morality, ch. 3:

p. 95: “Das Vergessen der Absichten ist die häufigste Dummheit, die gemacht wird” means “Forgetting our objectives is the most frequent form of stupidity.” The line is from Nietzsche’s The Wanderer and His Shadow, § 206. The immediately preceding lines in the Nietzsche passage are: “During our journey we commonly forget what its goal was. Nearly every profession is chosen and begun as a means to some end, but then continued as though it were an end in itself.”

p. 96: The reference to contraception might seem to come out of nowhere; but at the time that Fuller was writing, one of the contexts in which “natural law” (generally in the Roman Catholic understanding thereof) was most frequently invoked was in debates over the legality of contraception.

The phrase “brooding omnipresence in the sky” is a quotation from Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (1841-1935) – not to be confused with his nearly equally famous father – was an influential American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1902 to 1932. The famous line about free speech not extending to shouting “fire! ” in a crowded theatre comes from Holmes – as does, perhaps less happily, the line “three generations of imbeciles are enough! ” (endorsing the compulsory surgical sterilisation of those deemed by the government to be “mentally defective”).

The quoted phrase comes from Holmes’s dissent in Southern Pacific Co. v. Jensen (1917): “The common law is not a brooding omnipresence in the sky, but the articulate voice of some sovereign or quasi-sovereign that can be identified.” In later correspondence he added:

(One often finds on the internet, attributed to Holmes, a slightly different quotation: “that men make their own laws; that these laws do not flow from some mysterious omnipresence in the sky, and that judges are not independent mouthpieces of the infinite. ” But that is actually a quotation from Francis Biddle’s 1960 book Justice Holmes, Natural Law, and the Supreme Court, summarising Holmes’s position, and not a direct quote from Holmes himself. Caveat lector.)

Fuller’s claim that the internal morality of law has nothing to say about, e.g., “the progressive income tax, or the subjugation of women,” shows how far he disagrees with, e.g., Spooner, who thought all taxation and all forcible gender inequality indeed incompatible with that internal morality. Fuller would presumably have said that Spooner was mistaken because a legal system can survive perfectly well even if it holds whatever may be the wrong views on taxes or on gender relations. But I reckon Spooner thinks that the internal morality of law includes not only whatever principles ae minimally necessary for a functioning legal system, but also whatever is the most consistent and defensible development of those principles.

p. 97: “Es kann somit bloss ein Rechtsinhaltprinzip sein, das die rückwirkende Kraft von Rechtsnormen ausschliesst, nicht ein Voraussetzungsprinzip” means “It can therefore only be a law-content-principle that excludes the retroactive force of legal norms, not a presupposition-principle.” I take this to mean (maybe?): if retroactive legislation is illegal, this can only be because some particular law says so in its content, not because not being retroactive is requirement of any law considered simply as such.

p. 100: The Latin phrase that Fuller quotes from Coke has a couple of typos; “Judes” should be “Judex,” and “rai” should be “rei.” “Quia aliquis non debet esse Judex in propria causa, imo iniquem est aliquem suae rei esse judicem” means “Since no one ought to be a Judge in his own cause, it is furthermore wrong for anyone to be the judge of his own property.”

Incidentally, “Coke” here is pronounced “Cook,” just as William Blackstone’s name is pronounced “Blackston.” (Let’s not even get into how the Brits pronounce “Ratlinghope”; you will be shocked and saddened.)

p. 101: The poet criticised by Alexander Hamilton is Alexander Pope.

p. 105: “even if it has been described as sublime”: this is a reference to the following song from Gilbert & Sullivan’s Mikado:

pp. 118-121: Michael Polanyi (1891-1976) – not to be confused with his equally famous brother Karl Polanyi (which of the two is the “default” Polanyi, the one you’ll be taken to mean if you just use the last name, depends upon which portion of the intellectual landscape you’re inhabiting) was a Hungarian-born thinker of wide-ranging interests who was first a professor of chemistry and subsequently a professor of social science at the University of Manchester (u.k.). His Wikipedia page is worth reading.

p. 123: Fuller’s comment concerning “the existence of more than one legal system governing the same population” – namely that “such multiple systems do exist and have in history been more common than unitary systems” – is an important one to keep in mind.

Harold Berman, in his book Law and Revolution: The Formation of the Western Legal Tradition, expands on this idea when he writes:

p. 124: the “law merchant” (note that “law” is the noun and “merchant” the adjective; the term is an English rendering of lex mercatoria) is a system of late mediæval / early modern international commercial law that was created by merchants outside the government court systems, and “enforced” through reputational effects. More about it later in the course, when we get to Bruce Benson!

p. 125: “parietal rules” are rules governing student housing, particularly rules regulating visits from members of the opposite sex, though sometimes applied to other sorts of rules such as visiting hours in general. These were once more common than they are today, but such rules certainly still exist. Auburn’s housing rules are fairly lax, but AUM’s are much stricter, stipulating for example:

(The AUM policy seems to assume that all students are heterosexual. Questions to consider: Is this policy discriminatory against homosexuals, by in effect pretending they don’t exist? Or instead against heterosexuals, since homosexual students are allowed to have romantic partners visit overnight while heterosexuals are not?)

By contrast, when I was an undergrad at Harvard (1981-1985) I’m happy to say there were no restrictions of any sort on such matters. (Or if there were such rules, nobody knew what they were, and nobody enforced them or gave them a second thought.) As another example of Harvard”s rather relaxed attitude toward its students’ private lives, there was even one residence house (not mine) where the swimming pool had hours posted for all-male nude swimming, all-female nude swimming, and co-ed nude swimming, according to taste. (No longer so, I believe.)

When I was at summer school in 1980, by contrast, students of the opposite sex were not allowed in the dorm rooms at any time. If you wanted to visit someone of the opposite sex, you would go to the dorm and announce who you wanted to see, and then cool your heels in the waiting room until they came down. At least that was the theory. There were cases in which these rules were perhaps not strictly followed ….

p. 126: I’m very sorry to see Fuller misusing the phrase “begs the question” here. I expected better of him.

p. 130: “ex necessitate rei” means “from the necessity of the case.”

Remember the phrase “the enterprise of law”; we’ll later on be reading several chapters from a book of that title by the aforementioned Bruce Benson.

p. 141: The French phrase at the bottom means, essentially: “Experience proves that people will accept a change of ruler more easily than a change in their laws.”

p. 144: The Latin phrase [per] fas et nefas means, essentially: “By fair means or foul.”

Fuller’s Morality of Law, ch. 4:

p. 158: Jüdische Geschäft: “Jewish business.”

[p. 178: “the Supreme Court has wisely regarded as beyond its competence the enforcement of the constitutional provision guaranteeing to the states a republican form of government.”

Here again Spooner would likely disagree, regarding e.g. the impediments that white governments in the South placed in the way of black citizens voting as incompatible with a truly republican form of government. This again raises the question: if one finds attractive the approach that Fuller and Spooner share, should one apply it in mostly procedural ways, as Fuller does, or in heavily substantive ways, as Spooner does?]

LikeLike

I’ve read about 1/2 of the first chapter and just took a break to read your post, Irfan (and your notes/comments, Roderick). The distinction between moral-requirement type normative pressure and other types of moral normative pressure (whether one takes a broader or more narrow view of morality) seems obviously correct. We can express this perfectly well by distinguishing “the morality of duty” and “morality more broadly construed” (this is similar to Scanlon distinguishing “what we owe to each other” and the rest of morality). Might this do for most or many of Fuller’s purposes?

Fuller seems to muck things up with quite a few other elements. At least: (a) satisfying one’s duties as no more than something like making one’s contribution to minimally stable social conditions, (b) the non-duty-concerned rest of morality as being aspirational (and personal in the sense of pursuing personal virtue or excellence, a la Aristotle). I’m happy to leave this stuff behind and deal with an idealized Fuller* who just makes the clear distinction between the duty part of morality and the rest of it — and leaves it at that. (I realize that, with different emphasis and formulation, this covers much the same ground that you cover in your notes, Roderick, where you point out the three distinctions that Fuller fails to distinguish.)

Back to reading Fuller.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“The distinction between moral-requirement type normative pressure and other types of moral normative pressure (whether one takes a broader or more narrow view of morality) seems obviously correct.”

Inasmuch as I don’t find it obvious, could you say a bit more?

LikeLike

There are things that I have reason to do, even most reason to do, and then — distinctly — there are things that I must do. If I must take this left turn, that is different from this merely being the most advisable thing for me to do. Similarly, in the moral realm, it is not just that I have most reason (of a distinctively moral kind, however one defines that) to not needlessly inflict pain on you, but that I’m required (morally required) not to do this.

(Just what it is for X to be normatively required to perform A is something of a vexed question. Also: I’m here using ‘X is morally required to perform A’ or the like in a “thin” sense that references only what is normative for X. There might well be a “thick” use of ‘it is morally required to perform A’ or the like that references a familiar complex of correlated normative features across persons and their relevant positions or relationships — something like fitting guilt and required compliance from the agent position, fitting second-personal anger and reason to object or demand amends from the victim position, fitting third-personal moral anger and reason to object or demand amends for the victim from the observer position.)

LikeLike

“it is not just that I have most reason (of a distinctively moral kind, however one defines that) to not needlessly inflict pain on you, but that I’m required (morally required) not to do this.”

You’re repeating the claim, but not really motivating it (for me). From an Aristotelean standpoint, the virtuous person does the precise thing they ought, at the time they ought, in the way they ought, for the reason they ought, etc. (Of course the thing they ought to do can be a disjunction, even quite a wide disjunction.) I don’t see how to create daylight between the virtuous person’s having most reason to do X and the virtuous person’s being morally required to do X. Can you give a concrete example where you think they come apart?

As for the reactive attitudes, a lot (perhaps not all) of what you say there concerns duties to others. But of course that’s going to be only a subset of morality, not only for Aristotle but also for Kant and Hume and Mill.

Does any of this have to do with supererogation? Because I don’t think supererogation in the strict sense makes sense within an Aristotelean framework, where doing too much is a departure from the mean no less than is doing too little. But I think Aristoteleanism can handle the cases we’re tempted to treat as cases of supererogation, can explain what genuine truth we’re trying to get at there — I have a long song and dance about this (the very first paper I presented at Auburn back in 1998 or ’99, in fact).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I’m just repeating the same thing. The hope, though, is that putting the point in terms of very simple, commonly-used terms (rather than in terms of my semi-technical, semi-idiosyncratic mumbo-jumbo) will add some weight. That we have different terms (or sets of terms) in common usage generally indicates that we are referring to different things. Again: I can have most reason to take this turn (doing so can be the advisable thing to do) without it being the case that I must take it. (This is a pragmatic requirement. I think there are also, at least: requirements of personal commitment, rational requirements, requirements to comply with rules in a constructed practice, requirements of morality. Lots of musts!)

I think supererogation is one case of requirement coming apart from what one has most reason to do (e.g., it seems right that I have more reason to be respectful of others to degree N+1 even if I’m only required to be respectful to others to degree N). But there are probably other sorts cases (e.g., if there is no moral requirement with regard to promoting or realizing certain valuable things, one might still have most reason to promote or realize such ends to some specified degree). I’m curious about your Aristotelian explanation of the cases that we are tempted to or tend to think of as genuinely supererogatory.

(One family of views regarding the nature of normative requirement (one that I am sympathetic to) says this: when X is required to A, but not when X merely has most reason to A, the alternatives to A-ing are not merely outweighed, but ruled-out. Being ruled-out, in turn, comes to something like this: relevant background normative considerations make it such that the proper way to deliberate about whether to A does not involve even considering the alternatives to A-ing, except in special deliberative circumstances (e.g., when one is aware of a competing defeasible general requirement to take one of the alternative to A-ing). This account-schemata has holes in it and raises as many questions as it answers, but at least it puts some plausible-enough theoretical meat on my linguistic and metaphysical intuitions.)

LikeLike

Roderick:

I don’t either, but Fuller’s problem is worse than that. Fuller is trying to create daylight between the virtuous person’s being “required” to do X, and the virtuous person’s facing the “demand” to do X. What he says:

So the claim is that what is “required” is neither obligatory nor demanded. Outside of a divine command ethic I suppose it’s not “demanded,” but setting that special case aside, I don’t see the daylight between a requirement, an obligation, and what’s “demanded” of an agent. At best, there is a difference in tone or connotation here–an increasing “sense” of the imperative. But that’s very, very vague. “You are required to show up tomorrow,” “You are obliged to show up tomorrow,” and “It’s demanded of you that you show up tomorrow” all basically say the same thing.

LikeLike

Yeah. I mean, sure, some moral requirements are a bigger deal than others, but that seems to me a difference in degree, not kind.

LikeLike

Is it possible that Fuller is here using ‘requires’ in ‘what excellence requires of us’ in the non-normative sense (as when one speaks of what is required for something to count as having feature F)? Or that he is confusing normative and making-for or counts-as necessity? Courage might require facing down fears, but the necessity here is making-for necessity, not normative necessity (being normatively required to do this or that).

LikeLike

No. As I say in the post, Fuller’s distinction seems vulnerable to two kinds of counterexamples:

(1) Suppose we have a duty to make the best of the time we have across our expected lifespan. That’s both a duty and an aspiration, and is incompatible with the idea that the distinction between duty and aspiration is exclusive. The aspiration involved is a duty. Yet the idea that we have a duty to do our best–or make the best life for ourselves, or make the best use of the time at our disposal–is pretty common, shared by many people across space and time.

(2) Suppose that assiduous adherence to duty is aspirational. Then the distinction between aspiration and duty gets no purchase. If duty is a matter of rigidly consistent adherence, of the religious kind I mentioned in the post, then living up to duty is aspirational. It’s not something you can toss off. Likewise a highly intuitive thought to many.

What’s puzzling to me is Fuller’s admiring reference (and correct explication) of Aristotle’s doctrine of the mean on p. 19. Aristotle’s conception of virtue as a mean is probably the single most straightforward counter-example to Fuller’s distinction. Aristotelian virtue-as-a-mean is aspirational in Fuller’s sense, but makes essential reference to duties in Fuller’s sense. Yet it’s not two disparate, incommensurably different ethics glommed together; it’s a single coherent package with two integrated aspects to it, aspirations and duties. Aristotle’s doctrine of the mean was probably the canonical ethic of Euro-Mediterranean societies for thousands of years. No one can call it obscure.

Regardless of Fuller’s purposes, the distinction strikes me as involving a false dichotomy. Again, I don’t know how much of the rest of the book turns on this.

LikeLike

the distinction strikes me as involving a false dichotomy.

Agreed.

I don’t know how much of the rest of the book turns on this.

Very little, as far as I can see.

LikeLike

Well, I’m curious to see what happens next, then.

Incidentally, as far as our discussions themselves, I was thinking of having you start the sessions on Fuller by saying a few words on why you chose this book, and what role it plays in the research or pedagogical project you had in mind. Maybe also what you take to be its most important contribution. We often just sort of jump into a book without having a sense of why the person who selected it did so, but it may be worth having some background.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sure, I can do that.

As we’ll see, the book’s aims really come to focus in the Appendix (the “Grudge Informer” case), which Fuller and I both recommend reading before chapter 2. (The good stuff starts with the Nazis! Feel free to quote that sentence out of context.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Regarding your [1]. It might be that one must have a certain aspiration. That is correct. But I think your point here misses the mark. I take it that a morality of aspiration is a morality with non-requirement-type normativity (say normativity that is a function of intrinsically desirable moral ends and means to these ends) but no normative requirement. But if this is right, then, if the distinction here is to be illusory, one has to say something like this: moral requirements can turn out to be reasons of value promotion or realization and reasons of value promotion or realization can turn out to be requirements. This is tricky territory (what with various Aristotelian teleological explanations of duty or deontology and the recent-ish “consequentializing” strategy of formally eliminating deontology in terms that are formally consequentialist). But these two normative elements sure seem like different things to me, so I’ll need some convincing arguments to show me otherwise. In any case, the possibility or reality of a duty to have this or that aspiration will not get the right work done.

Regarding your [2]. Why isn’t this just a case of one having significant reason to exceed certain parameters in a moral requirement? Suppose I’m required, when pursuing some end of value or importance to me greater than 8 (scale to 10), I’m required not to impose costs of more than 2 on you. But I have significant moral reason to be extra respectful of you. So, being an extra-moral person, I try — aspire — to refrain from imposing costs of more than 1 on you (and perhaps, when I succeed, I’m supererogating and am thereby deserving of special praise). More importantly, in the case of simply aspiring to meet a genuine requirement (not to meet some standard that exceeds it), the normative requirement is prior (that’s implicit in the description). If anything like “taking on meeting the requirement as a goal that is valuable or worthwhile” is adding a normative element, it is an element distinct from the requirement. One might, instead, hold something like this: the requirement here consists in the agent taking on some valuable goal (or even just the standard being met being a valuable state). But now we are back to the Aristotelian or “consequentializing” reductive explanations of moral, normative requirement (or deontology). Maybe, in the end, one of these reductive explanatory strategies is right. But, again, this would be surprising and would take a lot of convincing conceptual argumentation.

LikeLike

Re (1):

But that just flatly contradicts what Fuller says. He says that a morality of aspiration involves requirements that aren’t obligations. So I don’t think my claim misses the mark at all. If the target is what he says, then I’ve hit it. You’re just re-describing his claim.

But suppose we re-describe it the way you like. I think the question has to arise: how is a listing of intrinsically desirable moral ends and means to them without a normative requirement to pursue them a morality at all? Fuller is trying to characterize a morality. What you’ve described is a list of desirable things. But a list of desirable things is not a morality. In general, I don’t think there’s any such thing as a “morality” that just points to a bunch of things and describes them as “advisable” or “desirable” or “preferable” in some weak, optional sense.

I suppose you could just re-imagine Fuller’s project altogether. But then I’d say you’re changing the subject. The topic of my post is Fuller’s strategy via the distinction he employs. My claim is that the strategy fails because the distinction fails. It’s not really a response to what I said re Fuller to re-invent a Fuller*, ascribe a new project to him, and then push the burden of proof to me convince you that this new, mostly undescribed, project is false because we can imagine a list of desirable goods that no one is obliged to pursue.

Re (2):

Because it just isn’t. The examples I gave are examples where you have a non-supererogatory duty the satisfaction of which is aspirational. You’re not “exceeding” duty in these examples. Rather: your duty is arduous enough that doing it is aspirational. And this is not some exotic, extravagant claim. Suppose you promise to do something. Now suppose that doing it is very arduous. Qua promise, it’s a duty. Qua arduous, it’s aspirational. Make it an iterated series of promises. Now you have an iterated series of duties taking an aspirational form. This happens all the time.

In insisting that there is a mutually exclusive distinction between aspiration and duty within morality as such, Fuller is treating such duties as non-existent or not worth integrating into his account. But it’s a problem for his view that literally hundreds of millions of people act on a conception of morality that flatly contradicts this claim every single day. I’m relying on the Islam example to get the “hundreds of millions” figure, but that wasn’t the only one I gave. Fuller’s distinction requires him to say that every case of an arduous duty that I gave has to be supererogatory, hence not obligatory. But again, that just flatly contradicts what the proponents of such duties have thought about them. If you promise to show up at work every day, and do a full, competent, productive day’s work every day, the satisfaction of the promise is not supererogatory. But living up to that promise involves the aspiration to become a fully conscientious worker. Those two garden-variety facts fly directly in the face of his claim. He can dismiss such views as outside the scope of his theory, but then he opens himself to having imposed an ad hoc distinction on morality while insisting that it characterizes morality as such. It doesn’t.

In short, he can either make an ambitious claim or a very modest one. If he makes an ambitious claim, he opens himself up to counterexamples like mine. If he scales the claim back, then it can’t do any of the work he seems to want it to do (whether it ends up doing that work or not, I don’t know). But his claim fails on either interpretation.

LikeLike

(A) I’m not sure what is meant by requirements that are not obligations. And I don’t know where Fuller makes the claim that the morality of aspiration (or the aspirational aspect of morality) includes requirements, but not obligations. (It can be required that I exhibit feature F in order to have virtue V, but this sense of ‘requirement’ is not normative. Maybe Fuller makes this sort of claim?)

(B) [“…how is a listing of intrinsically desirable moral ends and means to them without a normative requirement to pursue them a morality at all?”] Maybe I’m wrong, but I thought the idea was that there is some one thing, morality, that has both kinds of normative elements (roughly, reasons of value or desirability and requirement-type reasons)? And that he interprets the ancient Greeks as (implausibly) asserting that morality contains only non-requirement-type normative elements.

(C) [“I suppose you could just re-imagine Fuller’s project altogether. But then I’d say you’re changing the subject.”] It is possible that I’m just substituting what makes sense to me for what Fuller says. I’m not sure. Does Fuller think there are two things here (two “moralities”) or one thing (morality) with two features or aspects (requirement-type reasons, non-requirement-type reasons — with the latter interpreted in terms of aspiration to achieve valuable ends or the like)?

(D) [“You’re not “exceeding” duty in these examples. Rather: your duty is arduous enough that doing it is aspirational.”] Hmmm. I suppose the satisfaction of a duty is, in general, aspirational in the sense that, if satisfying the duty is not something that one can directly (easily, automatically) do, one satisfies it, if one does, by way of trying to do so. (It is not required here that satisfying the duty be arduous.) In this sense, attempting to satisfy a duty is like pursuing an end (or a valuable end) – and off we might go with a “consequentializing” strategy for explaining deontology in terms of teleology (valuable consequences or outcomes). However, I’m not sure this speaks to what Fuller means by aspirational morality (or the aspirational aspect of morality). Again, it seems to me that the sensible thing in the vicinity here is non-requirement-type normativity. If Fuller has something else in mind, I’m not quite sure what it is.

LikeLike

Irfan:

I think I got your [1] wrong in my earlier comment. Your point is not that one might have a duty to aspire to achieve this or that. Rather it is that we meet certain duties precisely by aspiring to meet them. I agree. But I would generalize to all or most duties: in general, we meet duties by aspiring — i.e., trying — to meet them. And (to bring the focus back to normative status) we have reason (and at least usually requirement-type reason) to aspire to meet a duty in virtue of our having requirement-type reason to actually meet it. So an aspiration can have requirement-type normative status. It need not have the normative status of realizing or promoting something that is (morally) desirable or valuable. So there is no distinctive non-requirement-type normative status associated with aspiration (and not with doing one’s duty). And so it makes no sense to speak of a “morality of aspiration” or “the distinctive aspiration-related element of morality.”

However, I’m apt to interpret Fuller charitably. And so to interpret his framing in terms of there being reasons of moral desirability as distinct from reasons of moral requirement (and in terms of how well one does at meeting one’s duty specifically as against doing what one has most moral reason to do more generally — relevant to Fuller’s “scale” of moral achievement). I suspect this is the central and on-target thing that he had in mind, despite his committing to the idea that aspiration is the home for a distinctive non-duty-related normativity (probably reasons of moral desirability).

LikeLike

The point you’re making in your first paragraph does capture what I was trying to say. Your second captures what Fuller was trying to say, but I’m still not convinced of its cogency.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your original examples, Irfan, do show just how demanding a religious Sunni Islam is. Yet I think we can often distinguish between core aspects of a rule — e.g. prayer every day — from the most exacting details (which could become so finely specified as to exhaust all available resource). On the other hand, perfectionist demands virtually by definition are infinite tasks; the target is a regulative ideal. Fulfilling a rule’s fullest details might sometimes be conceived that way, such that a threshold becomes an every-receding horizon. But this seems in some sense artificial to the realm of rules, whereas it is natural to the realm of perfection (Kierkegaard’s final Christian ethic is like this: he explicitly says the most saintly person has come no farther towards the goal than a scoundrel — their efforts are both “nothing” before God).

LikeLike

I take your point, but I don’t think my claim turns on the Islamic examples, or the special demandingness of Islam. Consider some very humdrum examples:

(1) You agree to get to work at 8 am. Insofar as it’s in your power, you always get to work at 8 am. (You’re never willingly late.)

(2) You accept employment as a hospital nurse. You unfailingly live up to your duties as a nurse.

(3) You accept employment as a hospital janitor. You unfailingly live up to your duties as a hospital janitor.

(4) You get married. You live up to your vows.

These are all cases of promises kept. But they’re promises such that adherence to the letter and spirit of the promise is aspirational. It only ceases to be aspirational if you define the norm of adherence down to a sort of mediocrity or minimalism. I don’t think it’s accurate to say that fulfilling the details of the rule (“keep your promise” or “live up to your job description”) is merely a regulative ideal. I would say, instead, that strict adherence (in the sense of plain old adherence, not supererogation) is more arduous than is conventionally imagined.

I’ve used promises, but I think one can alter the example and get the same result.

Coming the other way around, I think the demands of perfectionist virtue can be scaled down so as to avoid the Kierkegaardian predicament you describe. The demands of virtue can be relativized to human capacities and vulnerabilities so as to demand the best within the agent’s power, without demanding either too much or too little. That, I take it, is what the Aristotelian doctrine of the mean does demand. “The best” can denote a wide disjunction of permissible actions within a range, but some action within the range can be (is) required of the agent qua moral.

I guess I’m repeating myself (and repeating some of Roderick’s points), but the irony is that Fuller’s distinction between duty and aspiration bypasses Aristotle’s conception of the mean–while invoking it. I see Aristotle’s theory of virtue as one that (successfully) falls on both sides of Fuller’s dichotomy.

LikeLike

Here are more excerpts from my Philosophy of Law course handouts, for the next bit of Fuller:

Fuller’s Law and Morality, Appendix and ch. 2

pp. 245-249: This imaginary case of the “Purple Shirts” and the “grudge informers” is based on a class of real-life cases that arose in the wake of the Nazi period in Germany.

p. 39: Think about these eight criteria for law in connection with the arguments of the Five Deputies on pp. 248-253. Many of the Deputies’ arguments seem to be honouring some criteria at the cost of sacrificing others.

While Fuller’s reasoning is sometimes reminiscent of Spooner’s, his minimal content of law seems more procedural and less substantive than Spooner’s (though Randy Barnett has attempted to synthesise the two).

p. 59: “nulla pœna sine lege” means “no penalty without a law.”

p.68: “lex posterior derogat priori” means “a later law supersedes an earlier one.”

p. 69: Fuller treats “repugnant” as a weaker term than “contradictory.” I recall making the same mistake in a college paper in which I was interpreting an 18th-century text. (The professor didn’t catch my mistake, but I did, later.) Regardless of what “repugnant” means nowadays, the older meaning, or at least the older meaning that’s relevant here, was essentially synonymous with “contradictory.”

p. 73: Fuller characterises an analysis in terms of the interests of the ruling class as a “curiously Marxist argument.” He’s apparently unaware that free-marketers were giving that sort of analysis long before Marx. (Marx himself acknowledged his debt to the “bourgeois economists” on this score.)

p. 87: Fuller’s talk of the “intention of the statute” should remind us of Spooner.

LikeLike

Thanks, that’s helpful. I just read the Appendix, haven’t yet read Chapter 2. So far, I agree with Deputy 3. I have some sympathy with Deputy 2, but little with 1, 4, or 5.

The issue Fuller discusses in the Appendix remains a live issue: the same thought experiment applies to the future disposition of the West Bank, and Deputy 3’s comments are an astute characterization of the situation there.

LikeLike

What about …

LikeLike

Result of a search on “Deputy Dawg Palestine”

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-63596140.amp

LikeLike

A thoughtful post! Fuller’s distinction between the morality of duty and the morality of aspiration really shows how societies balance between what is necessary for order and what is ideal for excellence. Interestingly, this connects with how Islamic teachings guide us — some commands are obligatory (farz), while others are aspirational (mustahab), encouraging believers toward higher spiritual and moral goals.

For those interested in exploring such perspectives with an Islamic touch, you may like visiting my site Surah Yaseen where I share Quranic guidance and reflections that also highlight the balance between duty and aspiration in our daily lives.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment. I will definitely look up your site when I get a chance. And I do think that the power of Islamic ethics remains untapped in many ways.

Still, I tend to reject a sharp distinction between the obligatory and the aspirational, which is much like the distinction between the obligatory and supererogatory. The distinction makes sense if we imagine that the demands of the obligatory (of farz or fardh) are low. But if the demands are high, then it becomes aspirational simply to meet them.

I happen to think this is true of Islamic sharia. Take four obligations within Islam. It is clear that all four obligatory, and yet their demands are so intense that they make full adherence aspirational.

These obligations do not exhaust Islam, and yet I know few people who live up to all four of them in every detail. Doing so is an aspiration.

Coming the other way around, it seems to me that it is obligatory to have high aspirations. Falah is the highest aspiration, and yet striving for it is obligatory.

I think Aristotle’s theory of the mean captures the truth better than either Fuller’s distinction or the obligatory/supererogatory. Virtue is a mean, and we have an obligation to hit the mean on each occasion, where doing so is both an obligation and an aspiration. This demands doing our best, but doesn’t demand self-mortification or exhaustion. As the Qur’an puts it, “with hardship comes ease” (94:5). Oscillation between duress and ease is built into the concept.

LikeLike

That’s a very thoughtful perspective, Irfan. I completely agree — when we truly understand the depth of Islamic teachings, even fulfilling the fardh becomes a spiritual aspiration. The beauty of Islam lies in how its ethics inspire both obligation and elevation of character.

If you’re interested in exploring more about Quranic reflection and guidance, you might like https://suraheyaseen.com/

, where Surah Yaseen and other Islamic insights are shared to help strengthen one’s understanding and connection with faith.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for sharing this information

LikeLiked by 1 person