A revised version of this post has been published in Reason Papers, vol. 39:2 (Winter 2017), pp. 108-117. The link goes to a ten page PDF.

Here’s a link to the Reason Papers archive.

A revised version of this post has been published in Reason Papers, vol. 39:2 (Winter 2017), pp. 108-117. The link goes to a ten page PDF.

Here’s a link to the Reason Papers archive.

It’s a day of anniversaries.

For one thing, it’s Matt Faherty’s birthday. Happy birthday, Matt! His birthday was April 12. Whoops.

It’s also the late Christopher Hitchens’s birthday. Happy birthday, Christopher, wherever you are.

I got to know Hitchens during the 2000s, and we corresponded for a few years by email. Every year around this time, we used to joke about the fact that his birthday happened to fall on the anniversary of the Jalianwala Bagh Massacre of 1919.

Not that it was all that humorous a topic. Here it is, as depicted in the film “Gandhi.”

My grandfather–my father’s father–was there. Obviously, he escaped, or I couldn’t sit here and tell you about it. I never met him (he died in Pakistan when I was a small child), so I can’t pretend to have some powerful personal bond with him, or via him, with the event. But I’ve heard the family lore about him, and about 1919 (and 1947), so that’s the connection.

My biggest fear after 9/11 and our wars in Afghanistan and Iraq was that some day we’d repeat some American equivalent of Amritsar somewhere, and that I’d have to live as the citizen of a country stained with the blood of innocents like the ones at Jalianwala Bagh. Have we escaped that fate? Well, I can’t think of a literal equivalent of the Amritsar Massacre since My Lai, but then, browsing my way through the Senate’s Torture Report, I can’t say we’ve entirely escaped the Amritsar Syndrome, either.

David Cameron famously (or notoriously) refused to issue an apology for the massacre. It’s wrong, he said (in 2013), “to reach back into history and to seek out things you can apologise for.” I have mixed feelings about the statement, but in truth, he has a point: it’s one thing to acknowledge, but another thing to apologize for, an event nearly a century in the past.

As he prepared to leave Amritsar, Cameron explained why he had decided against issuing an apology. “In my view,” he said, “we are dealing with something here that happened a good 40 years before I was even born, and which Winston Churchill described as ‘monstrous’ at the time and the British government rightly condemned at the time. So I don’t think the right thing is to reach back into history and to seek out things you can apologise for.

“I think the right thing is to acknowledge what happened, to recall what happened, to show respect and understanding for what happened.

“That is why the words I used are right: to pay respect to those who lost their lives, to remember what happened, to learn the lessons, to reflect on the fact that those who were responsible were rightly criticised at the time, to learn from the bad and to cherish the good.”

The last word, however, goes to the birthday boy–the older one, I mean. Here’s a passage from Christopher Hitchens’s “A Sense of Mission,” an appreciation of The Raj Quartet (in fact, the appreciation that induced me to read The Raj Quartet, and make it one of my favorite works of literature, alongside A Passage to India). He’s referring simultaneously to the Indian Mutiny of 1857 and the Amritsar Massacre:

It’s not too much to say that these two symbols form the counterpoint of The Raj Quartet. On the one hand is fear–in part a guilty fear–of treachery, mutiny, and insurrection; of burning and pillage in which even one’s own servants cannot be trusted. On the other is the fear of having to break that trust oneself; of casting aside the pretense of consent and paternalism and ruling by terror and force. The persistence of these complementary nightmares says a good deal about the imperial frame of mind (Prepared for the Worst, p. 219).

“The imperial frame of mind”: I’d like to think that it’s all essentially irrelevant to us. In any case, when I think of the Jalianwala Bagh Massacre, as I do each year, I’m reminded of why I’d like to keep it so–or come to that, make it so.

Postscript: This article about Blackwater in Iraq almost got me to rethink my claim about our not repeating Amritsar. [Added later: I’d forgotten about Haditha when I wrote this. Here’s material on Haditha from Democracy Now, and an interesting but overly sanguine article from The Atlantic. The author of the second piece somewhat ingenuously writes, “In a liberal democracy…we put a very high burden on the state in taking away the liberty of a citizen accused of a crime.” Well, we ought to, and would like to think that we do. But it’s a stretch to assert that we do. Civil asset forfeiture is the most obvious counter-example, but the whole of the drug war provides another.]

Postscript 2: Horrifyingly worth reading, from the Hindustan Times: excerpts of Dyer’s testimony before the Hunter Commission.

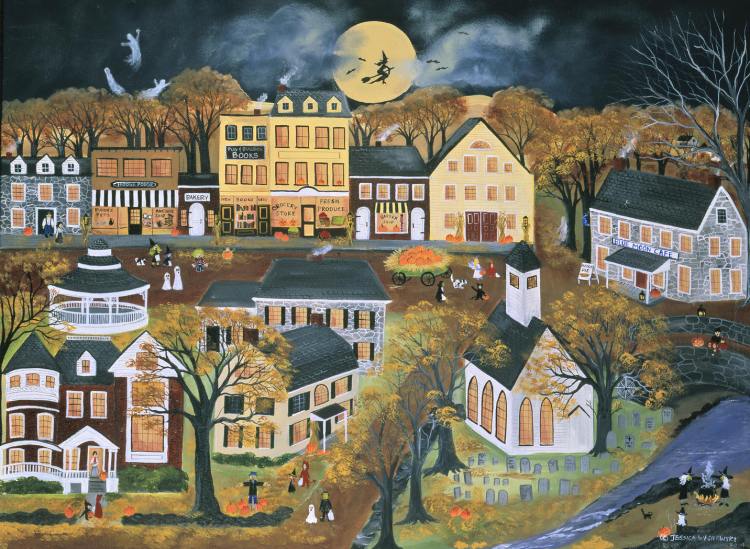

Halloween has, for as long as I can remember, been the only holiday I’ve ever been able to take seriously or wholeheartedly to celebrate. As an ex-Muslim, I have a certain affection for Ramadan, but Ramadan isn’t really a holiday, and unfortunately, none of the Muslim holidays (the Eids) are seasonal, seasonality being an essential property of a real holiday. (In fact, generally speaking, Muslims have trouble figuring out when exactly their holidays are supposed to take place–another liability of being a member of that faith.) Having spent a decade in a Jewish household, I have some affection for some of the Jewish holidays–Yom Kippur and Passover, though not Hannukah or Purim–but always with the mild alienation that accompanies the knowledge that a holiday is not one’s own: it’s hard to be inducted into a holiday tradition in your late 20s, as I was. I like the general ambience of Christmastime, at least in the NY/NJ Metro Area, but unfortunately, once you take the Christ out of Christmas, you take much of the meaning out of it as well–Christmas without Midnight Mass being an anemic affair, and Midnight Mass without Christ being close to a contradiction in terms. Not being a Christian, I find it hard to put Christ back into Christmas, mostly because I have trouble putting him anywhere at all.

The secular holidays are, I’m afraid, a sorry set of excuses for holidays. I’ve trashed Columbus Day on this blog, Independence Day on another, and I endorse Christopher Hitchens’s description of New Year’s Eve as the “worst night of the year” (and U2’s description of the Day as essentially unremarkable). Thanksgiving is too damn complicated, given its connection to family, and the political holidays (Presidents’ Day, MLK Day, Memorial Day, Veterans’ Day) are either too political, too contrived, and/or too somber to count as real holidays. Labor Day is a day off, not a holiday. It’s not the same thing.

So what’s left? The purest, most innocent, most seasonally appropriate, most nostalgic, and most celebratory of all holidays, Halloween. I’ll concede this much: El dia de los muertos, All Saints’ Day, and All Souls’ Day are all perfectly respectable cousin-holidays to Halloween and fit for post-Halloween celebrations, but their value supervenes on that of Halloween; in and of themselves, they don’t quite cut it, at least for me. (Scary thought: only a philosopher could manage to use the words “supervene” and “Halloween” in the same sentence.) What all four holidays have in common is a properly autumnal and properly macabre preoccupation with mortality, which is the only point of having a holiday in the first place. The point of a holiday is to celebrate life in the shadow of death–in the full knowledge that it’s there, lurking in the shadows and crevices of life, and in the full knowledge that though it’s there, we could care less.

It’s a near tragic fact that Halloween itself almost went extinct. I have nostalgic memories of Halloween from childhood, but sometime in the mid-80s, Halloween’s luster was dimmed by a series of candy poisonings, razor-bladed apples, and other scares (or so we were led to believe); I distinctly remember when Halloween was cancelled–abolished, outlawed–in my town in the mid-80s. It took a long time for the holiday to recover from its de jure abolition, and just as it seemed to have been doing so, it was cancelled two years in a row in the Metro Area for climatological reasons–for the freak snowstorm of 2011, and then for Hurricane Sandy in 2012. It made a comeback last year, and I’m hoping it makes a bigger one this year. All systems appear to be “go” for a comeback: Halloween falls on a Friday this year; the weather is supposed to be perfect; and judging from the neighborhoods I’ve seen across north Jersey, everyone–infants, adults, and everyone in-between–is more than ready to celebrate.

Every holiday has an aesthetic, and needs artwork to match. In recent times, I’d nominate Tim Burton as the Master Artist of Halloween. Going further back in time, I might award that title to Bram Stoker, Mary Shelley, or Washington Irving. (I know, I know: Poe or Hawthorne should be in there, but they do less for me. Feel free to come up with your own nominations and leave them in the comments.) Anyway, over the years I’ve been surprised to discover how many people–or at least, how many Americans between the ages of 20 and 50–have childhood memories of listening to some version of Camille Saint-Saens’s little piece, “Danse Macabre,” around Halloween-time. I myself remember listening to a version of it playing over an animated “filmstrip” (remember those?) of dancing skeletons, care of my grade-school music teacher, Mrs. Davidson–to whom I’m eternally grateful. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to find a video version of the filmstrip anywhere. That said, there are lots of versions of “Danse Macabre” online; I couldn’t quite find the perfect one, but this one had the right quirkiness about it. Enjoy.

P.S., For a more musically satisfying version of “Danse Macabre,” check out Clara Cernat and Thierry Huillet’s version for violin and piano, just a click away once the preceding clip finishes.

P.S., October 31, 2014: Here’s an amusing piece from the Times’s “Friday Files,” on Halloween celebrations from back in the day–1895, 1914, and 1926.

P.S., November 1, 2014: Well, Halloween certainly made a comeback in my area. Here’s a link to a local news story about the house featured in my header (which I’ll keep up for the rest of the weekend). You probably don’t want to miss this extremely frightening 38 second video:

It does seem to me that the general character of Halloween has changed since my day (the 70s and 80s) to accommodate the helicopter-parent/over-regulatory/risk-averse sensibilities of the modern age. Carrie-Ann Biondi points out to me that in most north Jersey towns, Halloween has now, by municipal fiat, been ordered to take place between the hours of 6 pm and 8 pm. So if you trick-or-treat before 6 or after 8, you’re breaking the law. And true to form, around 7:45, the po-po came by to clear everyone off the streets. There was a huge, festive block party in one of the decorated neighborhoods of Glen Ridge–the crowd there was in the hundreds–but most of the other streets were empty. So the trend is now toward adult-“organized” partying rather than the old undirected play of yore. I suppose that adult-organized is safer–and as with anything with the word “adult” in it, certainly has more sex appeal–than old-fashioned trick-or-treating, but it does seem to me that something’s been lost.

I can’t end this rant without saying that our municipalities need some push-back as far as their over-regulation of ordinary life is concerned. Libertarians and others spend a lot of time complaining about the over-reaching powers of the federal government, but the truth is that municipalities need to be curtailed as much as any other branch of our over-zealous government. There doesn’t seem to be any aspect of life immune to the paternalism of municipal ordinance (and lots of ordinary life that needs more regulation than it gets). Maybe that’s an argument for spending less time on blogs and more in town council meetings, pushing back on the people in Town Hall who perpetually seem to want to push the rest of us a bit too far.

Incidentally, Kate Herrick points out to me that my anti-non-Halloween rant missed Easter–true enough–about which I’d say more or less what I said about Christmas.

One last PS: Some examples of the paternalism I mentioned before, care of Carrie-Ann Biondi:

1. Seven weird laws regulating Halloween from various places.

3. More age limits.

4. Yet another curfew, from Fishkill, New York.

I try to keep the language clean here at PoT, but honestly, these laws seem pretty fucked up to me.

Respondeo:

Refuse! Resist!