This is the précis of a paper I’ll be giving at the virtual/online component of the 2026 conference of the Association of Practical and Professional Ethics, April 10, “From Diversity to Neutrality: Rebutting the ‘Key Move’ of the Kalven Committee Report.” Last year I gave a different paper at the on-ground version of the conference, discussing institutional neutrality’s failure to deal with institutional complicity in injustice.

Institutional neutrality is the doctrine that institutions like universities should refrain from taking public positions on matters of public controversy. The locus classicus of the doctrine is the so-called Kalven Committee Report (KCR) issued at the University of Chicago in 1967. According to the KCR, the core mission of the ideal university is the “discovery, improvement, and dissemination of knowledge” in the service of teaching and research. This mission, we’re told, requires the maximization of intellectual diversity, which in turn requires or entails institutional neutrality. I call this “the key move” of the KCR’s argument.

According to the key move, departures from institutional neutrality produce a “chilling” effect alleged to be endemic to hierarchically organized institutions: for any pair of contested propositions, institutional endorsement of one “chills” or disincentivizes inquiry into the other.

A first problem with this claim concerns the sheer implausibility of the thesis itself. Taken absolutely literally, KCR seems to be suggesting that the core mission of the university requires a consequentialist maximization of content-diverse propositions. Taken literally, this diversity requirement can be satisfied by tasking the university with the study of any maximal set of diverse propositions, however trivial, e.g., drawing out the decimal places of pi, or calculating a potentially infinite set of sums, or counting the blades of grass on campus, etc. That seems absurd.

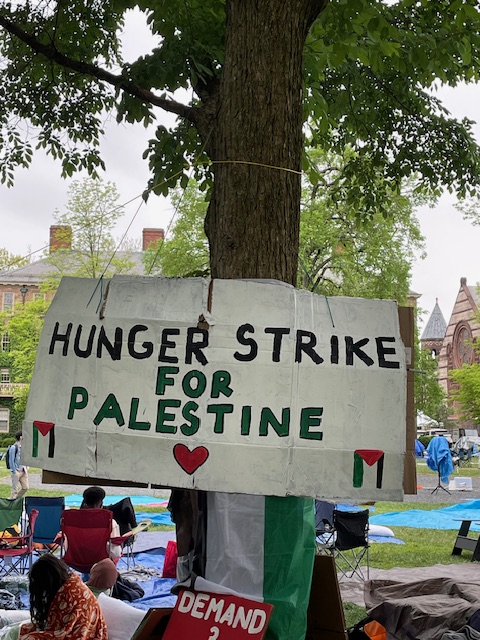

Gaza Solidarity Encampment, Cannon Green, Princeton University, May 2024. Cannon Green has been closed to protest on “neutral” grounds since 2024.

To avoid absurdity, an institutionally neutral university would have to adopt an academically relevant conception of diversity. As far as I can see, little useful work has been done on this topic, but waiving that issue, one problem here is that the conception of academic relevance in question would be controversial, and would require public articulation and defense. Since institutional neutrality proscribes the public avowal by the university of controversial claims, it seems to proscribe the public avowal or defense of any substantively interesting form of academically relevant diversity. If so, the very attempt to combine institutional neutrality with an academically relevant conception of diversity seems incoherent and self-defeating.

Suppose that it can somehow be done, however. The problem now becomes that institutional neutrality is neither necessary nor sufficient for diversity even on an academically plausible construal of diversity.

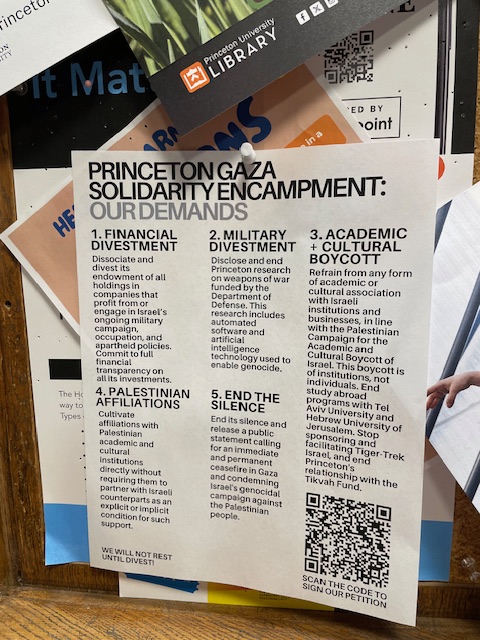

Not sufficient: an institution can chill speech and subvert diversity while endorsing institutional neutrality. It can, for instance, employ institutionally neutral “time, manner, and place” regulations to quash speech or expression that it finds problematic (thereby reducing relevant sorts of diversity). Institutional neutrality is of no particular help here. It can also impose neutrality on members of the campus community specifically in order to quash controversial speech, for instance, by making neutrality a condition of participation in “official” university events (thereby reducing relevant sorts of diversity). In this case, institutional neutrality isn’t just unhelpful, but the source of the problem. I illustrate both points by way of examples drawn from the conduct of institutionally neutral (or “restrained”) universities during the Gaza Solidarity Encampments of 2024, with particular emphasis on events I myself witnessed at Princeton.

Not necessary: non-neutral institutions can self-consciously commit themselves to the cultivation of diversity without endorsing institutional neutrality. To regard neutrality as a necessary condition of diversity is to regard it as the only viable basis for neutrality. But there’s no reason to think this, and no plausible argument for it has so far been offered by any defender of institutional neutrality (or anyone else).

The demands of the divestment camp at Princeton. The University recently canceled a talk by Norman Finkelstein on the putatively “neutral” ground that the talk needed institutional review before being approved.

Both Aquinas and Mill endorsed conceptions of “viewpoint diversity” as a condition of inquiry while explicitly rejecting anything like neutrality. A Thomist or Mill-inspired university could in principle follow suit. I illustrate this point by way of my experiences at two Catholic universities, the University of Notre Dame (where I got my degree) and Felician University (where I taught for twelve+ years), with particular attention to the presidency of Father Theodore Hesburgh at Notre Dame. Neither university endorsed institutional neutrality, but both permitted the flourishing of academically relevant diversity. It’s not clear what an avowal of institutional neutrality would have added to the promotion of diversity at either institution. And to the extent that both institutions occasionally failed to promote diversity (as they did), it’s not clear how or why institutional neutrality would have furnished the optimal remedy. Notre Dame, in particular, strikes me as a model of non-neutral viewpoint diversity, at least in the years (roughly 1990-2000) when I attended. (It’s not coincidental, I think, that Notre Dame was for many years the academic home of John Finnis, Alasdair MacIntyre, and Joseph Raz, whose work criticizes the defects of neutrality-fixated conceptions of liberalism.)

Dartmouth President Sian Beilock has argued that the key move is justified by appeal to the so-called Asch Conformity Experiments (1956), which illustrate the dangers of conformity to authoritative figures. The experiments, she suggests, show by extrapolation that university officials who make controversial claims undermine viewpoint diversity on campus. Her claims, I argue, systematically misrepresent the claims of the experiment. Contrary to Beilock, the findings of the experiment can’t be generalized to universities as such, and don’t underwrite institutional neutrality. Indeed, even if the findings could be generalized to universities, they wouldn’t underwrite institutional neutrality. If conformity to authoritative figures is a danger in cognitive life, it makes sense to teach students to deal with it. One reliable method is immersion: put students in promimity to authority, but expect them to exercise virtues of cognitive independence on the premise that the best way to learn how to deal with authority is to practice dealing with it.