Every now and then, in debates about the political economy of health care, you’ll run into the physician who declares that he’s had it with being called a “provider,” and won’t put up with it a minute longer. He went to med school, he got an MD, he walked uphill-barefoot-in-the-snow-both-ways, from anatomy and physiology to endocrinology and immunology–and back. He did an internship. He did his residency. He spent his nights on call, sleeping in the hospital. He’s a physician, goddammit, not a “provider,” and he refuses to be called by the latter name. That’s the problem with health care today, by gum. The insurers and administrators have taken over, using new-fangled “provider” jargon, and lost touch with the good old days, when MDs were MDs, and reimbursement was fee for service.

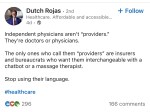

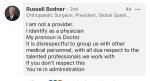

I probably sound like I’m exaggerating. But try some of these examples on for size, harvested directly from LinkedIn. (Click each thumbnail to get a better visual.)

Nazi card or not, these claims are nonsensical. Newsflash: Physicians are health care providers, just as professors are educators, or janitors are cleaners, or people who work primarily with their hands are laborers. There’s nothing to dispute here, just time and energy to be frittered away on a quixotic semantic battle masquerading as a noble crusade. They should be grateful that no one is calling them “consultants.”

Physicians’ resistance to being called “providers” has no more noble motivation than the elitist refusal to grasp that physicians are simply one set of service providers among others in a common enterprise, making separate but coordinated contributions to the same intended outcome, namely health. Nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, therapists, technicians, paramedics, EVS workers, and the like all make a significant contribution to health care. Making a significant contribution to health care is providing it. Providing something makes you a provider. Hence the term “health care providers.” No doubt a bitter pill to swallow, but no less true for that.

Pedants could argue about whose contribution is the “highest” or most valuable of the bunch, but all things considered, that inquiry seems a pointless waste of time and energy. Physicians are perhaps the best trained, most knowledgeable, and most skilled workers in health care, but nursing tends to involve more sustained and intense physical labor, and more prolonged patient contact and care. Paramedics are in general less medically knowledgeable or skillful than physicians or nurses, but often better at improvising in the field than either. And so on.

As an OR EVS worker, I regularly encountered the prejudice that the work I did in the OR was “menial” and “unskilled,” but cleaning and setting up an OR was work that no one else in the OR could do, and causally speaking, was work such that if it wasn’t done, and done right, nothing else could be. My father had a forty year career as a general and vascular surgeon, but neither he nor any of his colleagues had any idea how to mop, wipe, or sanitize an OR, or how to sterilize the instruments used in one. Anesthesiologists in our OR regularly threw thousand-dollar instruments into the trash because they wrongly thought they were disposable; coming the other way around, they insisted on re-using disposables because they wrongly thought that they were re-usable. It all goes to show that simplicity is not so simple. And menial work is not as menial as the average elitist would have you believe.

No one doubts that physicians are knowledgeable and skilled. What’s more readily forgotten is that every bona fide health care professional makes a necessary and valuable contribution to the provision of health care–maybe hard to measure in precise terms, but obviously there. We capture that fact by calling them all “providers,” even if some providers feel diminished by being reminded of the generic similarity they bear to the people “at the bottom.” But change the metaphor, and there is no “top” or “bottom,” just functional roles in a division of labor. If there’s one semantic or conceptual reform the workplace really needs, it’s dispensing with the idea that human relations are best conveyed by the metaphor of a pyramid whose glorious apex rests on some lowly base. More harm has likely been done and confusion engendered by that one metaphor than by any other in common parlance.

Elitism aside, the “call me physician” gambit reflects real political naïvete. What exactly is supposed to be accomplished, politically, by the insistence that physicians be called “physicians” rather than “providers”? How will doing so beat back the administrators and insurance companies that are making life difficult for…”providers”? The vague, woolly suggestion seems to be that the restoration of “physician” talk will restore the lost glory and dignity that physicians once enjoyed back in the day. Glory and dignity restored, physicians will once again be able to look the administrative bean counters and denials reps in the eye, demand their fair share of whatever’s being distributed, and put a stop to all these denials and downgrades, along with all this pre-authorization nonsense.

Why, exactly? How is this supposed to work? Every insurance company’s denials division employs legions of physicians whose lives are dedicated to denying the claims of hospital-based physicians or physicians in private practice. These insurance-based physicians have MDs just like every other physician. Telling them that you are a physician, dammit, will do nothing to neutralize their power, or the power of the insurance companies they work for. Because, dammit, they’re physicians, too. Sad but true: you can’t stop a juggernaut with a word or an attitude.

The insurance companies are hardly ignorant of the fact that they’re dealing with physicians. As with banks and bank robbers, that’s where the money is. What they doubt is that it matters who they’re dealing with as far as resistance is concerned. And they’re right. It’s not a matter of who they’re dealing with. It’s a matter of what these aggrieved providers intend to do to beat back the tide of insurance denials. But if the first thing they think of doing is to detach themselves from all other providers, crowning themselves the Kings of All Providers–with fancy titles to go with it, and deference to follow–they can bask all they want in their sense of self-importance, but they should prepare for political defeat. Because defeat is where they’re headed. No struggle worth fighting can be won by cultivating a sense of self-importance. Vanity is an own goal.

The situation we face is characteristically American. A bunch of rugged individualists manages to drive themselves into the ground by insisting on their rugged individualism. Gradually, the rugged individualism becomes a form of elitism, but that doesn’t get them out of the hole they’re in, either. The obvious solution becomes crucial to grasp but impossible to see: they have to devise a form of collective action in as broadly based a coalition as they can manage. But collective action is a habit that they lack, and the capacity to sustain a coalition requires a sense of solidarity they’ve never had. It’s a good recipe for being eaten alive, if that’s what you’re after.

You can either flail at a word, or struggle against an adversary. You can’t do both. You have to set priorities and pick one. Let’s hope the providers figure that out sooner rather than later, for our sake as well as theirs.