I have spent my whole adult life as a libertarian or classical liberal of one kind or another. And throughout this long period—for I am not young—I have been puzzled as to whether I should think of myself as leftwing or rightwing or centrist, or whether I should, like many libertarians, reject the conventional left–right political spectrum altogether. So now, herewith I propose to try to sort this out.

I would like to get to the bottom of a distinction that seems fundamental and eternal, which since the French Revolution has gone under the heading of “right wing” vs. “left wing.” I definitely don’t mean whatever distinguishes “liberals” and “conservatives” in contemporary American politics. I mean to pick out the distinction that seems to run very deep in social conflicts that are not merely about competing material interests, but that have an ideological root or at least a strong ideological component. The distinction I’m looking for—assuming it really exists—would be deeper than any ideology and would in fact would be a psychological, structural basis of ideologies. This is something as old as the Gracchi vs. the Roman patricians, as Cleisthenes vs. Isagoras, as Thersites vs. Odysseus, and probably older.

Is there such an eternal, fundamental opposition as I’m looking for? Or is there just a mess of conflicting values and concerns, à la the Schwartz theory of basic values? I suspect what I’m looking for exists, or why do political contests so often seem to be recognizably “left” vs. “right”? But then, what is fundamental to this opposition?

To begin with, here is an unsystematic list of ideas that seem to me to be central to the opposition I’m looking for.

| Left | Right | Remark |

| Openness to experience | Conscientiousness | OCEAN |

| “Barbarism” | “Civilization” | Right interpretation (per Kling) |

| “Liberation” | “Oppression” | Left interpretation (per Kling) |

| Equality | Inequality | |

| Anarchy | Hierarchy | |

| Change | Stability | |

| Disruption | Preservation | |

| Innovation | Tradition | |

| Chaos | Order | |

| License | Rules | |

| Subversion | Authority | |

| Risk | Safety/Security | |

| Empathy | Distance |

On the other hand, some ideas that do not seem to capture the Left–Right opposition:

| “Left” | “Right” | Remark |

| Universalism | Nationalism | |

| Internationalism | Patriotism | |

| Communitarianism | Individualism | Or vice versa?? |

| Liberty | Subjection | Or vice versa?? |

| Collectivism | Individual rights | |

| Command economy | Free market | |

| Smart | Stupid | |

| Reason | Dogmatism | |

| Flexible | Inflexible | |

| Weakness | Strength | |

| Female | Male | |

| Impurity | Purity | |

| Autonomy | Heteronomy/Control | |

| Adventurous | Timid | |

| Nurture | Nature | |

| Progress | Stasis |

Analysis

Looking at the first table, it seems clear to me that the “first principal component,” as it were, of the left–right split is what I might call “equality–hierarchy,” and the second principal component is something like “change–tradition.” Thus, the main conflict is between those whose main concern is the plight of the marginalized and those whose main concern is to maintain the existing order, including the prerogatives or authority of those who rank higher in that order. This can take many forms: aristocrats vs. commoners, rich vs. poor, educated vs. uneducated, masters vs. slaves, strong vs. weak, rulers vs. subjects, star-bellied Sneeches vs. plain-bellied Sneeches. The “marginalized” in this opposition need not be wronged or oppressed in any way, although they often may be. Moreover, the authority or rank of the elites need not be illegitimate or socially harmful. Indeed, some sort of hierarchy seems to be a practical necessity for the good functioning of any community larger than a few dozen people.

The second component of conflict is between those who want to introduce new ways of doing things and those who want to preserve the traditional ways. On the one hand, traditions gratify our natural preference for the familiar and predictable and safe; on the other, change gratifies our liking for novelty, surprise, and risk. We all have both sets of preferences; the question is one of balance. We cannot do without both tradition and change. Without tradition, culture would not accumulate, and cumulated culture is the storehouse of human know-how at the root of our success as a species. But without change, growth is impossible.

It is obvious how concern with preserving hierarchy and with preserving tradition go together, since hierarchies (or at least the social structures within which hierarchies emerge)—like every other cultural asset—are maintained by traditional practices. By the same token, concern with the marginalized and with promoting change go together, since improving the lot of whole classes of people is making a change and often a profound change in cases where their marginalization is due to deeply embedded traditional practices.

Test Cases

We can test the account of left vs. right given above against our intuitions about specific cases.

According to the present analysis, movements like abolitionism for chattel slavery, ancient Athenian democracy, English anti-monarchism in the 17th century, the French revolutionaries, the communist revolutionaries of the 20th century (Russian, Chinese, Cuban, Vietnamese, Cambodian, etc.), trade unionism, and Fabian-style welfare programs in advanced Western countries (such as the New Deal and later Great Society) all code as left.

On the other hand, Nazism and Italian Fascism code as right, despite being—like communism—totalitarian, revolutionary, populist, and redistributionist, because their ideological rationale emphasizes (a) preservation of traditional values/culture/blood, etc. rather than change, and (b) promoting the glory and strength of the nation rather than the interests of the marginalized. Thus, the insight of the horseshoe theory of the political spectrum is preserved at the same time that the intuitive left–right distinction between communism–fascism is accounted for.

Note that context matters in making these determinations. The views of John Locke or a pro-democracy Athenian citizen in 500 BC might not seem leftwing today, but in their time they clearly were.

Note also that an advocate’s own conception of an issue is an important element in explaining its “left” or “right” status. For example, environmentalism today codes as left, even though it is preservationist and not about helping marginalized people. I interpret this as due to the association of environmentalism with antagonism to commercialism, consumerism, industrialization, and business and capitalism in general. From the beginning, environmentalism has seen itself as fighting industrial business practices (think industrial waste, exploitation of natural resources—forests, minerals, fossil fuels—air pollution) and consumerism (garbage, plastics, personal consumption). None of this strikes me as inherently left, but combined with anti-business sentiment, it becomes so. Business is associated with wealth- and income-inequality, the hierarchy of business organizations, and the unequal size of corporate behemoths vs. small business and consumers. The left is thus naturally hostile to business (more on this below), so it makes sense that they would embrace the environmentalist cause—and similarly the global warming cause when it came along later.

The anti-business sentiment of the left also helps explain another potential puzzle case: nuclear power. My understanding of the history of this is that left opposition was originally focused on nuclear weapons and later expanded to include nuclear power. I interpret the left’s hostility to nuclear weapons as due to pacifism and hostility to militarism. Again, I don’t see these as inherently left (as neither would Lenin, Mao, or Che), but it’s easy to see why the left would embrace pacifism in the context of warring nation states. Wars between nations—which are less common now but were formerly ubiquitous up through WWI—were often essentially wars between monarchs competing for glory, territory, and loot, in which the people were pawns. This includes the soldiers, although it’s not clearly irrational for poor young men with little other prospect of advancement to seek it through military service. But war is nearly always counterproductive, and it is the common people who suffer most from it. Moreover, military values reinforce hierarchy and its associated traditions. In this context, it makes sense that anti-war sentiment codes left. Thus, the pump was primed particularly on the left for campaigning against nuclear weapons. It didn’t hurt that our leading adversary of the time was the Soviet Union, which the left was sympathetic to. Nuclear power came to be bundled with nuclear weapons in the simplifying slogan “No Nukes.” The simplification was encouraged by the association of nuclear power with business interests, utility companies, and the cozy relations between these and government.

Anti-abortion codes right, which might seem puzzling on two counts. First, the unborn are clearly marginalized. Second, whether or not the arc of history bends towards justice, it does seem to bend towards tender-heartedness. More accurately, there is a clear correlation between prosperity and tender-heartedness. As societies become wealthier, they provide ever more generous private and public support for the indigent. What is considered acceptable vs. “indecent” neglect of the poor shrinks relentlessly, in step with increases in people’s ability to help. (I have often thought, for example, that John Locke’s non-inclusion of “welfare state” services among the functions of government had less to do with his supposedly being a proto-libertarian than with the simple fact that even the richest countries in the 17th century were too poor to seriously contemplate such things.) Also, the scope of those considered worthy of concern and assistance expands as wealth increases, as new groups of the marginalized are progressively discovered, today including even nonhuman animals. It seems likely that the compassionate feelings that drive the increasing levels of concern and assistance that accompany increasing wealth are not newly aroused by that wealth. Rather, the compassionate feelings were always there, only they were inhibited by practical necessity. And it is pretty obvious, on the analysis given here of left vs. right, why the leading edge of expanding compassion should code left. For, on this analysis, the foremost component of left thinking is concern for the marginalized. And this is why left support for the practice of abortion might seem puzzling. The expansion of tender-heartedness ought to include expanding concern for the unborn, as it has for the elderly and other groups. In hunter-gatherer societies, the abandonment to death of unsupportable old people and infants is nearly universal. As societies increase in material capacity, such practices come to seem abhorrent and are disallowed as immoral. So it makes sense that this attitude should eventually include the unborn, independent of the idiosyncratic dictates of any particular religion, and that the left should be at the forefront of this development. And yet the left, in the U.S. at least, vigorously supports the practice of abortion.

But of course, the origin of the left position on abortion in the U.S. today isn’t really mysterious. Historically, the interests of the unborn were preempted by the interests of an earlier-recognized marginalized group: women. The advocates of women’s interests from very early on included among their demands contraception and abortion rights. Moreover, these prerogatives really are in the interests of women, and women and feminists remain an important component of the left coalition in the U.S. Meanwhile, left support for abortion has been hardened by the fact that various enemies of the left oppose the practice of abortion. These include the Catholic church, whose deep traditionalism (especially in regard to its treatment of women) raises hackles on the left, and evangelical Christians, who are if anything even more traditionalist than the Catholic church—and certainly more rightwing—and moreover plausibly embrace an anti-abortion position precisely as a weapon against both sexual liberation and women’s liberation. Given this situation, the left today is pretty well locked into support for the practice of abortion, even though, given a different historical trajectory, it might well have been otherwise. But I will make a prediction: within the next 100 years, assuming our civilization continues to make material progress of the kind it has made over the past three centuries, the left will flip on this issue. More broadly, a general lesson from consideration of this issue is that to understand which policy positions will code left vs. right, historical contingencies are important. It is not enough to examine the objective merits of an issue.

A more truly difficult left–right split to explain on my theory might be gun control. On one side, I think the left is motivated to support gun control mostly by the desire to prevent harm and sees gun violence as a major source of needless suffering, especially among the urban poor. On the other side, gun ownership began as legal and has been for a long time, so a traditionalist will be averse to seeing this changed. These seem like relatively weak reasons, however—especially the latter—and indeed gun control is the norm in most advanced countries. It is reasonable to suppose that what makes America nearly unique among advanced countries on this issue is the 2nd Amendment, which enshrines gun ownership as a constitutional right. This has given the right a weapon with which to resist the left’s utilitarian, harm-reduction-based calls for gun control, a weapon which the right has proved eager to exploit. It is this eagerness which I find somewhat difficult to explain. I think it must be due to a combination of rightwing hostilities: to government and to the left. I think that in the U.S., the right has inherited a mistrust of government power that goes right back to 1776, which has been sustained in part also by a traditional celebration of self-reliance on the right. Meanwhile, the left for its part, especially since the New Deal, sees state power as an ally to which it accordingly shows far less mistrust. In addition, rightwing resentment of and hostility to the left is a strong force that probably helps explain its intransigent resistance to gun control. This is reinforced by a rural vs. urban cultural split on gun use. The gun violence of concern to the left is mostly urban, which codes left, whereas gun ownership is most likely to be seen as natural and normal in rural communities, which code right. These factors together seem enough to explain the sharp split between left and right on gun control in the U.S. Still, most of these factors are contingent from the point of view of my theory of left vs. right. Of course, this actually confirms the theory to the extent that the gun control issue is not inherently right–left valenced. Gun rights, like free speech rights, tend to be embraced more or less warmly depending on a party’s relationship to those who are in power. Would V. I. Lenin have advocated gun control in pre-1917 Russia? One suspects not.

Finally, I think any theory of left vs. right ought to be able to explain the longstanding penchant of the left for vilifying the United States. I don’t refer to leftwingers on X tweeting about how “ashamed,” “not proud,” etc. they are of their country because of whatever current or historical event they happen to be bloviating about at the moment. I mean rather the animus against America per se—against Americanism—that seems to have been embedded deeply in the left from practically the beginning of the 20th century on. This rarely erupts in full-blown diatribes against the U.S.—though sometimes it does just that, of course—but it comes out in incidental digs and obiter dicta all the time, such as in remarks along the lines of how the U.S. would be so much better of a place if it were more like Europe, etc. This is interesting in part because of the historical change it represents. In the late 18th century, the U.S. coded left in world historical terms, and very much so, and I think this remained mostly true through the 19th century. But by the mid-20th century, the situation was reversed. Why?

Clearly, at its inception, the U.S. was the rebel upstart fighting the monarchical power of England. The fledgling U.S. was founded on the new liberal principles of liberty and legal equality and the abolition of hereditary status, freedom of religion, and so forth. All this codes left in a big way, but as I have pointed out, historical context matters. In the late 18th century, the liberty and legal equality of commoners and bourgeoisie vis-à-vis monarchical power were leading political issues. By 1950, such issues were long-settled in all advanced countries, and the left had moved on long ago to other concerns. Principal among these were the hardships endured by the working classes, especially as contrasted with the comparative opulence of the “capitalists.” It is obvious in terms of my theory how compassion for the hard lives of working people codes left, but I doubt that that is sufficient to explain leftwing hostility to Americanism. After all, working class hardships were not unique to America. Moreover, they were ameliorated in time due to various factors, not least of which was a general rise in living standards brought about by capitalism itself. But leftwing hostility has remained constant to this day. What seems essential is the market order (“capitalism”) itself and the ideology of economic freedom that goes with it. These both seem essential to America, particularly the ideology of “free enterprise,” for reasons I have to admit I don’t really understand. I believe that this ideology, and to a lesser extent the practices it encourages, are what fundamentally arouse leftwing hostility, for three related reasons. First, the emphasis on personal responsibility makes no provision other than voluntary charity for those who cannot stand on their own two feet. From the left standpoint of concern for the marginalized, this seems callous. Second, even worse, the system seems driven by selfishness and even to present the pursuit of self-interest as a good thing. As Adam Smith famously says, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.” Third, however beneficial to everyone the consequences of the market order demonstrably are, including for working people, those consequences are certainly not the result of conscious design, much less benevolent intentions. In short, there is no compassion or concern for the poor and marginalized anywhere in the system of capitalism. As a result, to a person whose central political motivation is compassion and concern for the poor, capitalism must be an object of deep mistrust at best and of deep hatred at worst.

It gets worse. Thus far, I have described why capitalism even as a theoretical ideal should arouse leftwing hostility. Unfortunately, as we all know, the actual practice of capitalism is never ideal. Furthermore, the typical failures of actual markets to live up to the ideal are just such as to invite further leftwing ire. I am thinking of the cozy relationships between business and government in the form of protectionist measures, laws and regulations that place outsized burdens on small competitors or impose barriers to entry by potential new competitors, subsidies, tax loopholes, regulatory capture, abuse of eminent domain and other coercive measures imposed on the public for the benefit of business interests, and so on. All these practices tend to benefit business interests over the public interest and big businesses over small ones, in a cycle that works to preserve a coterie of vested interests at the top of the economic pyramid in perpetuity. To the extent that actual business practices work this way—which is substantial, even in the U.S.—support codes right, opposition codes left, and capitalism, even as a theoretical ideal, is stigmatized by association. And so the U.S., the capitalist nation par excellence, is a special target of left hostility.

In summary, the present model of the left–right opposition posits equality–hierarchy as the primary dimension of difference, with the impulse to equality motivated by concern for the interests of marginalized people and the impulse to hierarchy motivated by concern for effective social systems, competence, and fairness (in the sense of reward for merit and for success under the established rules), as well as for the interests of already-advantaged people. It posits change–tradition as a secondary dimension, with change motivated by desire for novelty and innovation and improvement and tradition motivated by caution and the desire to preserve what is tried and true. Although independent, it is evident that these dimensions dovetail, with the desires for equality and change mutually supporting each other, as do the desires for hierarchy and tradition. These two main dimensions seem sufficient to explain most observed left-right divides, in the present-day U.S. as well as in other eras and other countries. No doubt, however, the model could be improved by adding further dimensions. When it comes to explaining particular cases of left–right opposition, it is important to pay attention to historical context and to each party’s own conception of the issues, not only to the objective features of each case. Although historical contingencies often somewhat influence which positions code as left vs. right, I believe my discussion has shown that the particular constellations of positions that count as “left” vs. “right” are less arbitrary than is sometimes alleged.

Classical Liberalism: Left, Right, or What?

Lastly, I stated at the beginning that the stimulus for this investigation was to settle for myself the question of what view a classical liberal or libertarian should take of the left–right opposition. Is a classical liberal on the left, the right, the middle, or somewhere else altogether? Given all I’ve said so far, I think the answer is pretty clear.

I’m going to take it without any further elaboration or justification that the defining concern of classical liberalism or libertarianism is liberty vs. oppression. “Liberty” here means personal liberty in the sense of freedom from coercion, including freedom of association and respect for property. Given this definition, it seems clear that the classical liberal/libertarian concern is pretty well orthogonal to the left–right opposition. An indication of this has already been alluded to above: that a pro-liberty view coded left in Locke’s time (and for a century and a half thereafter) but is usually coded right today. If the context is the struggle for liberation from monarchical and hereditary-aristocratic coercion, then classical liberalism/libertarianism codes left; if the context is better working conditions for impoverished laborers, then classical liberalism/libertarianism codes right. And this is true even though the classical liberal/libertarian stands for the exact same legal and institutional rules at both periods.

What explains this, I think, is that whereas the classical liberal/libertarian concern is defined by a relatively fixed set of principles, the left–right opposition is much more contextual. What individual liberty requires, where this is defined negatively as absence of coercion, is relatively determinate, despite all the latitude for variation and fuzziness we know it allows. By contrast, “concern for marginalized people” can crop up in almost any social context, since there is almost no context where some group of people (or animals or whatever) cannot be regarded as marginalized individuals apt for compassionate concern.

In general, the main dimension of difference for the left–right opposition is equality–inequality, yet no particular basis is specified for what is considered equal or unequal. That is, the equal and unequal are not rooted in any special conception of justice or fairness or harm or marginalization. Therefore, practically any inequality can be regarded as a case of marginalization. In cases where the marginalization on a left analysis involves coercion, the left analysis is liable to align with the classical liberal/libertarian analysis; but where it is not, not. Thus, classical liberalism/libertarianism and the left–right opposition are more or less independent of each other, just as many classical liberals/libertarians have always said.

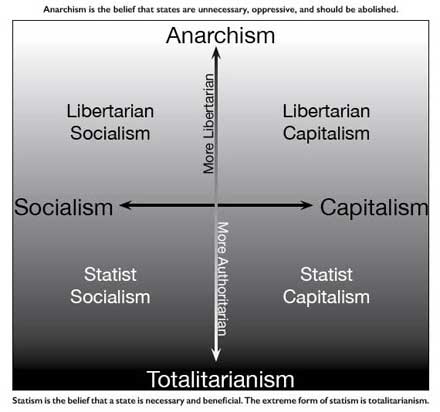

I note that this fact seems to have become widely recognized in recent years, as evidenced by what seems to be a new standard for depictions of the political spectrum, which are two-dimensional instead of the traditional one-dimensional left–right spectrum. For instance, when “ChatGPT” (3.5) was released a year and a half ago, one of the controversies surrounding it was whether ChatGPT was “woke.” Attempts to measure this were usually presented in the form of charts like this:

Note that the left–right and “authoritarian–libertarian” dimensions are depicted as orthogonal, consistent with my model (as an approximation: I doubt the two dimensions are literally orthogonal).

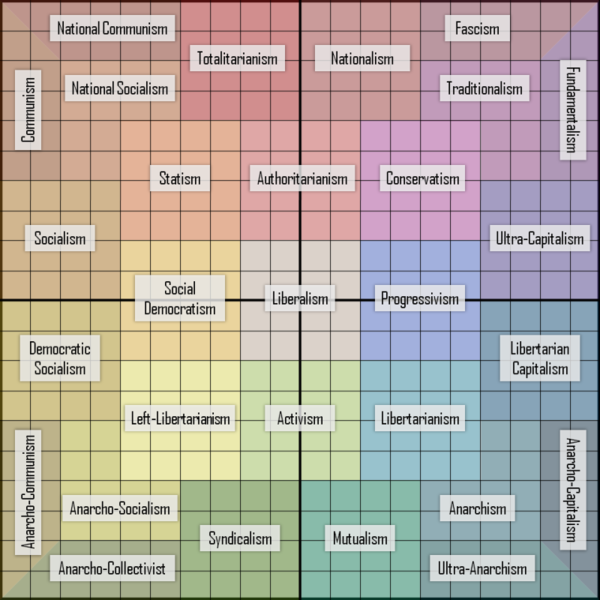

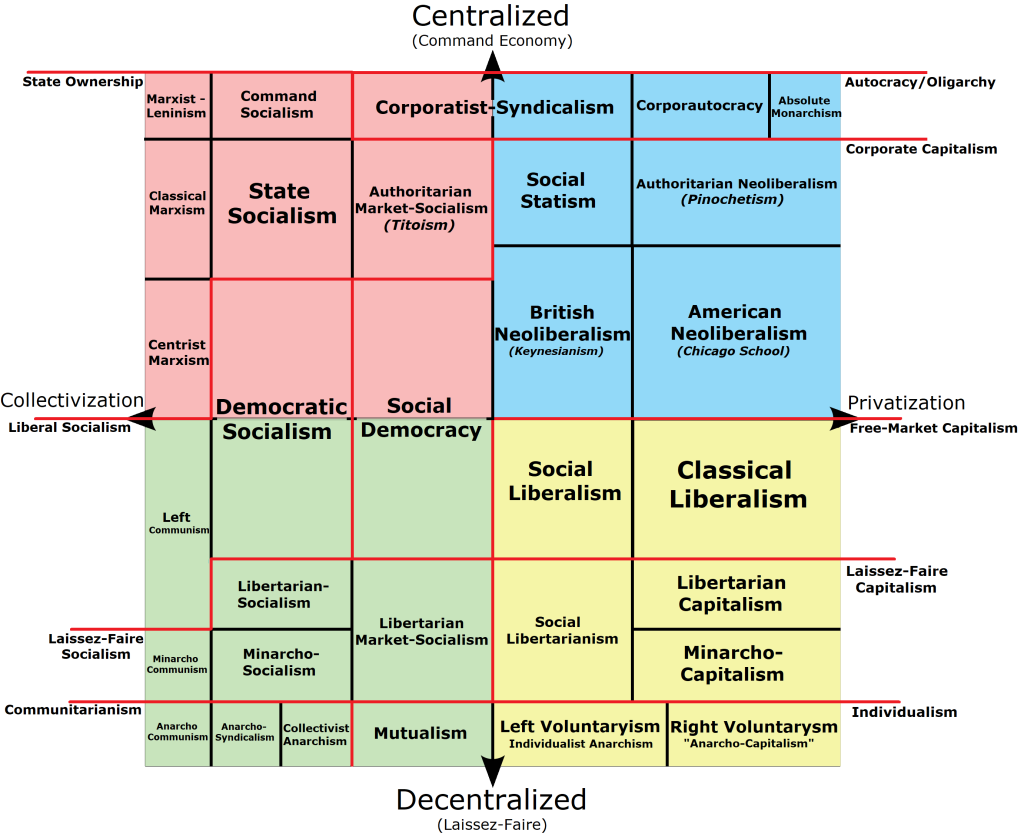

Two-dimensional graphs of this kind have become commonplace, though of course not universal. Figure 4 shows some examples.

Predictably, there is a fair amount of variation, not to say confusion, about what “left” and “right” represent. This seems right, actually. My argument has been that there is really nothing stable about the left–right opposition, which varies greatly from one context to another.

What then is the place of the classical liberal on the political spectrum? I wouldn’t care to try to make my own 2-D political spectrum diagram for the present-day U.S. However, I’m inclined to see classical liberalism as being more-or-less equally concerned with the interests of the marginalized and the interests of hierarchy. So, whatever such a diagram would look like exactly, I imagine the classical liberal would be somewhere near the middle of the left–right axis and somewhere near the “liberty” pole of the liberty–oppression axis. But what distinguishes the libertarian or classical liberal is not a position on the left–right dimension, but being toward the liberty pole of the liberty–oppression dimension.

An alternative perspective:

https://bleedingheartlibertarians.com/2012/11/the-distinctiveness-of-left-libertarianism/

LikeLike

I don’t think that the Left can be understood in abstraction from a concern with justice. The standard left-wing criticism of classical liberalism is that its focus on liberty understood as freedom from coercion and respect for individual rights is too narrow to cover the range of moral concerns relevant to social life. And the Left’s critique of the Right is that the Right is either indifferent to injustice, or actively committed to perpetuating it. I don’t think this concern for justice can be reduced either to individual rights or to compassion. It’s a distinctive, normatively irreducible commitment. And it’s at the heart of what makes the Left the Left.

Personally, I don’t think it’s necessary or desirable to come up with an account of the Left that precedes the Enlightenment or the French Revolution. The Left strikes me as a distinctively modern phenomenon, a response to a certain aspect of modernity. I don’t think it can coherently or usefully be applied to the world prior to that. The application of Left and Right to, say, Thersites and Odysseus strikes me as strained. There are huge swatches of history where the Left/Right distinction has no clear application. But once we get to the part of history that’s driven by the specifically European conception of modernity, the distinction starts to make sense.

Phrased in terms of justice, the idea behind the Left is this: We inherit from both ancient Greek and traditional religious thought the idea of an all-things-considered justice. Aristotle has “general justice,” and religious traditions have divine justice. Aristotelian general justice is the application of all of the moral virtues, considered as a unity, vis-a-vis others within the context of a common good, on the model of the polis. Divine justice is the idea that our overall virtue is judged in each moment by an omniscient and omnibenevolent authority whatever our circumstances.

Now recall the thought we associate with Kant: unless justice prevails, human life is pointless. Suppose this is true. In that case, modern life really seems pointless. It’s not clear how to put a zealous, moralistic commitment to justice into practice in the modern world, i.e., the world that comes into existence in Europe via the Renaissance. This is the world brought into being by Machiavelli, Francis Bacon, and Hobbes: of ruthless, amoral mastery over the world and over others. What we gain in power in a world of this sort, we lose in the capacity to enact a comprehensive conception of justice.

Adam Smith’s understanding of capitalism makes this obvious (the passage you quote from The Wealth of Nations makes it particularly obvious), but the modern theory of the firm makes it grotesquely explicit. Capitalism is driven by the profit motive. The profit motive has nothing to do with justice. The two can sometimes accidentally coincide, but there is no inherent connection between them. This is painfully obvious to me working in health care, but it’s fairly obvious anywhere you look. Everyone in a capitalist society feels the tension between virtue and the profit motive in virtually everything they do. If they don’t, it’s either because they’re broke or because they’ve forgotten what justice really is. Honesty, integrity, and justice are obvious liabilities in market competition and obvious liabilities in modern political life as well. To try to live by them in a fully zealous, fully consistent, fully committed, and totally uncompromising way is a death wish.

Given this, classical liberalism invites us to ditch justice and settle for liberty, but that’s as unsatisfying as the “free will theodicies” of natural theology, and for much the same reason. Something inside us tells us that we deserve more than mere freedom, not just in terms of what we get from others but in terms of what we give them. So there’s always a temptation to rebel against someone or something that says, “No, you don’t deserve more. Shut up, stop striving, and be content with the fact that you’re better off than everyone who’s worse off than you. And here are the statistics to tell you exactly how many of those people we’ve counted up.”

In short, the price of enjoying the riches of modernity is the loss of one’s virtue, and of one’s soul. As far as prosperity is concerned, the inhabitant of modernity is either producer or consumer, but as far as justice is concerned, he or she is put in the position of a perpetual spectator, watching the perpetual defeat of justice–with a big salty box of popcorn in one hand, and an ice-cold Coke in the other. The instruments of modernity make prosperity possible at the price of injustice. Every modern liberal regime began in horrific, unspeakable injustice. Every such regime demands amnesia about those beginnings. Every one anesthetizes virtue along the way, then celebrates the plenty that results from the taming or domestication of virtue.

The moral and political outlook of the Left is a party-pooping rebellion against the preceding predicament. The Left insists, in the face of what seem impossible odds, that justice must be done in the Old Testament spirit (“justice, justice you shall pursue”) so that life can have whatever meaning it’s supposed to have. Often, this commitment seems completely quixotic, such as when people figure out that the only collective power they have to put justice into action is the power of punishment-through-cancellation. But, they figure, a quixotic power is better than nothing. Often, it comes across as an inchoate longing for the primitive. That’s a crude acting-out on the realization that our noblest conceptions of justice have no traction in the modern world. But modern capitalism is interested in production and consumption, and justice isn’t something you produce or consume. There is no real market for it, just limitless demand served by a pitiful supply.

I don’t really regard myself as a member of the Left (or the Right). What I find admirable about the Left is that it represents the last gasp of justice on Earth–justice making its last stand before it’s swallowed up by State and Corporation. It’s easy to bring up the worst features of the Left (or the worst versions of the Left) as a means of discrediting the Left as such, but it’s not an accident that across the last century, every movement for justice in American life has come from the Left: the civil rights movement, feminism, the anti-war movement, the labor movement, the movement for transparency in government and commerce, the movement for gay liberation, etc. It’s hard to think of anything comparable from the Right or center, both of which had to be dragged kicking and screaming toward justice in every one of these cases.

But whether you share that estimation or not, justice strikes me as an essential motivation of the Left. There is no Left without justice. The contrary may also be true.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Irfan,

Thanks for this stimulating comment. Naturally, I disagree with pretty much all of it 😊, but that’s how our thinking develops. Speaking of development, I have to say that I am working out these ideas as I go along. Right from the beginning of my participation on this blog, I have noticed, somewhat to my surprise, that I seem to be a conventionalist about morals. What caused me to notice it is that everyone else here seems like a staunch realist. And so there has been this contrast. But it has remained inchoate, at least on my part. Moral and political philosophy is at the opposite end from my specialization, so I’ve never felt very qualified to talk about it. My primary goal for the next let’s say two years is to change that. The last couple of months have been pretty hectic, as I arranged my retirement, and the summer will probably be as well. So, progress may be slow at first, but eventually I hope to produce something worthwhile—and to blog a lot more than I’ve been able to do in the past seven years.

I don’t know how much of an irrealist I actually am, and one of my top priorities will be to figure that out. I find it very difficult to accept that there’s no such thing as the human good. In that way I seem to be a realist. On the other hand, I regard “morality” as a special way of thinking about or framing decisions: distinctive in that it precludes cost–benefit considerations. The effect of framing an issue as “moral” is precisely to rule questions about cost and benefit out of bounds as inappropriate. There are various reasons why we might have evolved the capacity for moralistic thinking. The obvious reason—or anyway, what comes to mind first for me—is to solve collective action problems. But I think there are many other cases where utility-maximizing reason falls short (sticking to an exercise plan, for instance). In this light, “morality” is simply the code of rules that we frame in this special manner. They may help us live better—but not necessarily. There are plenty of examples of unfortunate moral rules. But whether good or bad, moral rules are cultural-evolutionary products downstream of other factors, especially material conditions, but also emotional reactions and other things. A simple example is food taboos, which may evolve for various reasons. When they are a response to material conditions such as toxicity of certain foods, they are liable to be beneficial. But regardless of that, their status as moral—i.e., as non-negotiable prohibitions—consists in nothing more than that we treat them that way. And we treat them that way, namely as “moral,” ultimately because if our respect for them depended on finding good reasons, then we wouldn’t be able to respect them. So, this is a pretty deflationary view of morality! Morality as such has no special value. Moral rules sometimes contribute to the human good, sometimes not, hopefully more often the former than the latter. It is no different than dietary or child-rearing or hunting practices in this regard.

So, part of the reason I don’t identify the left as “the party that is concerned with justice” is that I don’t think justice is a fundamental. On the other hand, the opposition between chaos and order is fundamental to human experience, as I briefly described in the post. In a lesser way, I think the opposition between equality and hierarchy is also fundamental. Hierarchy per se is necessary and good, but it is very often abused (even when the form of hierarchy itself is unproblematic, which it often isn’t), and this sets up conflict. I don’t see any reason to suppose these two fundamental oppositions only arose or became important with European modernity. Maybe consciousness of a left–right opposition only arose late. Probably this is true, since I can’t think of any discussion that gives a central role to anything like a left–right opposition (or a chaos–order or equality–hierarchy opposition) in any pre-modern literature. But that’s no reason to suppose that these forces were not at work. If you think about the history of ancient Athenian democracy, for example, there were basically two parties, for and against, and it seems pretty natural to describe them as left and right.

But the main reason I wouldn’t say justice is an essential motivation of the left is that I don’t agree, in very many cases—maybe even in most cases—that what they are fighting for is justice. Leftwing fights to ban nuclear energy, pass environmental protection legislation, address climate change, enact some kind of universal medical care, free childcare, forgive student loan debt, ban plastic straws, and the like—none of these are justice movements. Notwithstanding that their advocates use phrases like “climate justice.” Calling it justice doesn’t make it so. These movements are often rooted in a desire to aid those deemed less fortunate, as my analysis predicts (and I addressed many of the nuances in the post), but that is just not the same thing as justice.

Your own list of “movements for justice in American life” isn’t much different: “the civil rights movement, feminism, the anti-war movement, the labor movement, the movement for transparency in government and commerce, the movement for gay liberation.” The civil rights movement I’ll grant you, but the status of the rest as “movements for justice” is at least questionable. Take feminism. Taking the long view—beginning in the year 1800, say—this was a movement to give women equal legal status, voting rights, and, most importantly, social equality with men. Is any of this really about justice? Maybe, but I’m not so sure. The patriarchal arrangements of the past were rooted in material conditions that encouraged a pretty strong sexual division of labor in which women were homebound while men did heavy labor, hunting, and fighting. This was the situation for the entire history of our species until just a few hundred years ago. I don’t think it was generally regarded as unjust (which is not to say women were happy about their status). This is an example of what I meant when I said above that morals are downstream of material conditions. What happened in the 19th century isn’t that we suddenly gained insight into moral reality that had eluded us before, but that the material conditions changed. The machine age arrived, and with it prosperity, eased living conditions, far less brutality, and “knowledge work.” In short, women’s liberation happened because it became possible. But this was a 200-year cultural evolutionary process, part of which required rethinking women’s nature and capacities. That is, I think women used to be considered men’s natural inferiors. This justified (or rationalized) women’s inferior social status. This would be why women’s second-class citizen status wasn’t regarded as unjust and why the crusade for female equality doesn’t feel like a justice crusade to me. To be clear, all I’m challenging here is whether feminism should be considered a justice movement. I would not deny that the early advocates of women’s equality were visionary and of the left.

The same sort of thing is true of gay liberation. The social position of gays was rooted in the public perception of homosexuality, which was divided between whether it was morally degenerate or a psychological malady. Changing the social and legal status of gays required changing that perception. It wasn’t a simple matter of identifying and calling out an injustice, because whether there was any injustice in the first place depended on that perception. As for anti-war, labor, and official transparency, these might in certain ways be about making the world a better place, but I don’t see any of them as primarily about justice.

Along with your list of left-initiated justice movements, you remark: “every movement for justice in American life has come from the Left… It’s hard to think of anything comparable from the Right or center, both of which had to be dragged kicking and screaming toward justice in every one of these cases.” I mostly agree, and this fits my analysis. The right is the party of stability, the left of change, both for better and worse. So, even where the right does mount a crusade for justice, it’s often not on behalf of something really novel. Rightwing crusades aren’t unheard of, however. The mid-20th century liberty movement, in the Mont Pelerin Society and others, is an example, I think. (Unless you want to say they’re actually leftwing, but I don’t think they’re usually thought of that way. On my own analysis, they’re neither.) Rightwing resistance to communism, when the left was pushing it and denying what was going on in the U.S.S.R. and other communist countries, would be another example. I don’t think this should be regarded simply as pigheaded resistance to progressive ideas. I think they thought communism was morally wrong. One could also name the anti-abortion movement, which I discuss in my post. That’s not a movement I would embrace myself, and one could say they have mixed motives there. But most movements have mixed motives, and I don’t think the justice element in the anti-abortion movement is deniable.

It is evident that we have quite different ideas about what justice is. Just as an ordinary language concept, it seems that justice is done when people get what they deserve. But that’s just to say that the concepts of justice and merit are analytically tied together. It does not much constrain what justice substantially is. Different ideas of justice reflect different conceptions of what people deserve, and these can vary quite a lot. What is due to a person can be thought to depend on their personal merit or virtue, on their actual accomplishments, on their contributions to a project, on nobility of birth, on bare personhood, citizenship status, age, profession, and on and on. Also, exactly what is due to an individual in light of his status can vary quite a lot. There are people today who think that if someone cannot obtain healthcare when others can, that is unjust. There are or have been other places where people think that if the prerogatives of noble birth aren’t respected, that is unjust. And so on. You may think that there is a real justice, which particular community standards of justice approximate with varying degrees of success and by which particular community standards should be judged. But, as I explained above, I don’t think this.

Capitalism is a system of justice, isn’t it? Isn’t this a pretty standard libertarian view? Justice is what happens when people’s rights are respected. Injustice is what happens when people’s rights are violated.

On behalf of capitalism, I would suggest that it is a system that aligns the rules of justice with economic efficiency. That’s not everything, perhaps, but it’s a lot. All things considered, prosperity beats the hell out of poverty. (In cultural-evolutionary terms, this probably helps explain the rise and spread of capitalism and its correlative conception of justice.) Plus, it leads to profound knock-on benefits—see the discussion of feminism above.

It might seem to be a flaw in capitalism—maybe this is part of your complaint—that it doesn’t distribute economic rewards on the basis of moral merit. As Hayek points out (Constitution of Liberty, chapter 6), this is a necessary feature of a system of liberty. In such a system, there is no central authority distributing goods or rewards. Rather, rewards are distributed to those who offer something that others want to buy, and people are much better able to judge the value to themselves of goods for sale than the moral merits of those who offer them, the effort and ingenuity that went into producing them, and so on. I would add that the disconnect between moral merit and material reward is probably a necessary feature of any social system, not just capitalism, and for the same reason as with capitalism: it is no easier for a central authority than for anyone else to know the moral merits of individuals. There has never been any social system where material rewards corresponded to moral virtue, and it is hard to see how there ever will be.

However, it is not at all true that capitalism is amoral. Capitalism depends essentially on people’s virtue. In fact, I seem to recall posting a long essay on this blog about this very matter. It is true that the game of capitalism is about the self-interested pursuit of money. But it’s not a free-for-all. The game has rules, without which it cannot function. These rules are the rules of justice (capitalism style: respect for others’ rights). Moreover, for capitalism to function optimally, greater moral virtue is required from community members than merely refraining from violating others’ rights. High economic efficiency requires that people be scrupulously honest, forthcoming with information, including information unfavorable to their own interests, trustworthy, non-litigious, and so forth. And remarkably, life in a market order and the inclination to fairness seem to reinforce each other: fairness in economic games such as the Ultimatum Game and Dictator Game is correlated with exposure to markets (Henrich et al., 2010). Again, market-based societies tend to be high trust societies, and vice versa. My interpretation of this is that in a market-based society, people are accustomed to seeing cooperative and fair-minded behavior working to everyone’s advantage and become habituated to such behavior. In non-market societies, people’s situations are more often zero-sum, and they are habituated to behave accordingly (i.e., “every man for himself”). Whatever the explanation, the correlation between markets and “impersonal prosociality” is what we empirically observe. (For much more on this, see Joseph Henrich, The WEIRDest People in the World.)

Which brings me, finally, to your remarks about the “predicament” of the modern world of “ruthless, amoral mastery over the world and over others,” in which “honesty, integrity, and justice are obvious liabilities,” virtue and justice are dead, and life is meaningless. These claims strike me as bizarre, frankly. I’m reminded of this cartoon, which I saw just yesterday. The weirdest part is the idea that modernism, starting with Machiavelli, Hobbes, and Bacon, initiated a soul-destroying world of amoralism, as though previously there had been somewhere—in Europe, apparently!—a moral paradise of justice and virtue. Whereas it seems clear to me that there has never been a gentler, kinder, more upright, accommodating, helpful, and nurturing world than one we are blessed to inhabit today. Life is precarious, of course, and not everyone is nice. But if there’s ever been a better world in actual reality than what we enjoy today, name it.

Unfortunately, it’s taken me a while to make this reply, and on Sunday I’m leaving for the Galápagos Islands and won’t return for nearly two weeks. So, I don’t know if there will be time for another round before I leave. But I would be happy to pursue this further in however disjointed a manner.

LikeLike

David,

I definitely intend to respond to this, but unfortunately, my schedule is very tightly packed, so that I only have a single day in any given week on which to write. So my response will be much delayed, but I’m not ignoring you.

LikeLike

Good timing. I have connectivity for the first time in 3 days, sitting in a restaurant called Muelle Darwin in Puerto Ayora on Santa Cruz island, Galapagos. (They have wifi.) If our luck holds, will be back in the U.S. on Friday.

LikeLike

For the next week, I will almost certainly have connectivity, and will have it for the duration, but will have it while sitting in cubicle C-37 on the eighth floor of the BASF Building, in the Business Analytics and Reporting Division of the DRG Downgrades Unit of CorroClinical, in a town with the confected corporate name of “Metropark, New Jersey.”

I could rest my case there. Where is the justice?

LikeLike