How to Fix the United States: Amendments and a Constitutional Convention

At this point, it must be obvious to everyone paying attention that the United States is a nation in deep trouble. Over the last two decades, both the effectiveness and democratic credentials of the US federal government have gone into decline, which has helped to drive increasing political polarization and public frustration that steepens the decline. More of the public turn to extremist politicians promising to eviscerate their political enemies, which makes the compromises needed in the American federal system totally impossible. Even the basics cannot get done: a single senator holds up over 300 military officer promotions for many months; a group of six radical House members out of 435 cause a government shutdown by holding up funding bills.

At least ten different kinds of constitutional crises could come about during and after the 2024 presidential election. These range from a candidate nominated by a major party, but is who is convicted of a felony before the November election and continues to run, to a candidate elected via the Electoral College and confirmed by Congress but sworn in from a prison cell until he pardons himself – and the Supreme Court perhaps rules that pardon invalid. It is also possible that one or more states will ban the same candidate from the ballot on grounds of insurrection by invoking Section 3 of the 14th Amendment – with violence ensuing if the Supreme Court upholds that ban. And one or more state legislature may award its state’s presidential electors to someone other than the winner of their statewide popular vote. If this happens because the popular vote winner is also a convict, or because a statehouse majority declares thousands of valid votes in their state to be full of non-existent fraud, mass riots again seem inevitable. And if one or two independent candidates win a couple state’s electors, we could see the presidential election thrown into the House of Representatives – and decided with one vote per each state delegation – for the first time since 1824.

This is just the most visible tip of the iceberg. Behind the scenes, the Supreme Court has been eroding the capacity of federal administrative agencies, including the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), to enforce statute-based rules. The Court is also handing control of more issues back to the fifty states, making efficiency and coordination for national goods impossible in many areas. Few large nations have even ten different teacher, counselor, and social worker certification systems, or ten school curricula, hospital systems, public health standards, and sets of insurance regulations differing by region. Having fifty in the US fragment labor markets in such sectors and makes coordination to prevent the spread of pandemic viruses impossible.

Self-Reinforcing Problems in the Systems. The dangerous loss of governing capacity in Washington D.C. has implications for the entire world: it could make the United States a less reliable partner in fledging efforts to unite nations that generally (albeit imperfectly) respect human rights and democratic values against the axis of tyranny and gang rule being cultivated by the regimes in Moscow and Beijing. From Venezuela, Belarus, Afghanistan, Iran, Syria, South Africa, Myanmar, Ethiopia, Sudan, to Nicaragua and the Sahel region in Africa, new dictators and kleptocrats are yoking their regimes to Putin and Xi with the goal of extracting maximum wealth for themselves whatever the costs – including the destruction of democratic institutions and values.

Moreover, from some of these countries, refugees stream in their millions into Europe and North America, provoking ethno-nationalist backlashes within the receiving populations that drive more voters towards racist politicians. This further weakens democratic constitutional structures. Recent surveys have found that around 40% of the refugees who have arrived in New York City during 2023 are from Venezuela alone (and this was entirely preventable: the US, with Brazil and other Latin American allies in the lead, could have brought down Maduro’s horrific totalitarian regime, which has bled Venezuela dry, years ago). In such a perfect storm of multiple vicious feedback loops, it is absolutely crucial to repair the American constitutional order before it is too late.

My recent book, The Democracy Amendments, describes the breakdowns that prevent the US national government from seriously addressing problems in immigration, public education, health care, college costs, high rates of lethal drug addiction and asthma, climate-driven extreme weather disasters, increasing economic inequality driven in part by the rise of new mega-oligopoly corporations like Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Apple, insolvency in the Social Security trust fund, and a swiftly mounting federal debt (caused partly by major tax cuts in 2001 and 2017) with annual interest payments now at $475 billion for fiscal 2022. That equals roughly two-thirds of all Medicare expenditures for seniors. Big legislative “breakthroughs” have been few and partial – only the “Obamacare” expansion of health insurance coverage, with all its gaps and inefficiencies, and Biden’s bill to repair aging infrastructure, which ended up including lots of “pork” but less than half of the needed investment.

A number of analysts, including most recently political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, now argue that America shows most of the historical hallmarks observed in ostensibly democratic nations that collapsed into failed states or vicious dictatorships. Even new secessions and/or civil war are becoming possible in the US. Nor is there much that political leaders in Congress and the White House can do to fix this institutional failure, even if they really wanted to. That is because the root causes lie in the federal constitution as interpreted mainly by federal courts. As Matt Ford has argued, under pressure from gerrymandering and the rule of big donors, our legislature is now much less representative and responsive to voters than it once was. The two main political parties have learned to exploit every flaw in US constitutional law to maximize their power and create an unbreakable duopoly. With so many gerrymandered safe seats in the House of Representatives and no runoff component in congressional elections, members of Congress have more incentive to spoil the other party’s proclaimed plans than to pass anything substantive of their own to secure national and global public goods.

Attitudes in Congress are so jaded that much of the legislation proposed by party leaders is only for show, or to whip up ideological fervor among their base: they know that they will never actually have to pass into law a bill to criminalize all abortions from conception on, or to pay trillions of dollars in reparations for slavery and segregation, because virtually nothing but budget bills can clear the Senate filibuster. It was once a rarity reserved for special cases, but now in its “non-talking” form, the filibuster has become routine. This is a huge obstacle that no other developed democracy in the world faces: their upper legislative chambers are often less powerful than the US Senate, and virtually all can take final votes by simple majority rule – just as the framers of the US constitution in 1787 intended. The same holds for upper chambers in state governments: no filibusters there.

In addition, partisan broadcast medias in the US face fewer of the basic regulations needed to preserve public goods that other democracies are willing to impose. After US television and radio stations were freed from the “fair and balanced” requirements that used to reduce systemic lying and partisan propaganda, they were captured by the same forces that control the two main political parties. Now some big television channels demand party loyalty and severely punish any moderate politician who tries to work with the other side for the common good.

When we add in the dominance of small-population states in the US Senate, and a Supreme Court turned highly partisan by trickery and a president elected by a minority of voters, legislative routes to address national problems – including dysfunctions in the federal system itself – are almost entirely closed. Congress will not, for example, require the kind of civics education that could reduce the appeal of conspiracy stories and reverse the pollution of our collective epistemic capital by mass medias selling addictive lies, hatred, and outrage. But even if they did pass such a landmark law, today’s Supreme Court would probably strike it down as an infringement on states’ rights. The Court has also gutted the Voting Rights Act (VRA), despite its nearly unanimous renewal in Congress during 2009 and George W. Bush’s signature. As a result, states across the nation are making it harder to vote. And the American Senate cannot even discuss a new VRA with balanced national voting standards that would expand both access to the polls and restore wide public trust in outcomes.

Without deep structural changes, Congress will never be able to reduce health care costs, adopt a reasonable program to limit greenhouse emissions, reach a bipartisan compromise on growing immigration problems, cut entitlement spending and raise taxes sufficiently to balance the budget, or take even small steps on gun reform like passing a universal background check requirement. Similarly, the power of a few tech giants gives them ever-greater market shares, but federal courts have rendered our century-old antitrust laws virtually useless (as Amazon, facing an antitrust lawsuit, will probably demonstrate again in federal court). And the grip of big lobbies willing to back challengers in low-turnout primary elections makes the new drive to strengthen those laws a huge longshot. Basic common sense legislation is nearly impossible in this environment. Puerto Rico statehood will never come up for a vote in the Senate, even though its residents have now voted three times to request statehood. Cryptocurrencies and ransom payments that fuel cybercrime, drug warlords, human trafficking, and tyrants like Putin and Maduro are still legal and operating with little regulation. Congress is also unable to kick out obviously corrupt members.

As The Democracy Amendments explains, in principle, Congress could write and pass strict anti-corruption standards that apply to its own members, Supreme Court justices, and the entire executive branch. It could require congresspersons to hold more meetings with constituents, and increase the size of the House of Representatives, which has been the same now for a century while our population tripled (see Federalist 58 on the fear that this would happen). Arguably, Congress could impose an 18-year term limit on Supreme Court justices and lower court judges. Congress could also mandate ranked choice voting (RCV), which “worked splendidly” in Alaska in 2022, in all federal elections. This would promote more moderate candidates and allow third parties to stand a chance. When used in primary elections, RCV could also reduce the problems caused by winner-take-all primaries on the Republican side, which enable a candidate to win all the delegates in many early states while getting only 35-45% of the votes because opposition to them is split between several other candidates.

But despite broad public support for these procedural fixes, they would all meet instant death by Senate filibuster, veto by leaders of the two dominant parties, or Supreme Court rulings (which continue to gut anti-corruption standards). At a result, the only feasible way to make Congress work again, or clarify impeachment standards, or insulate the Justice Department from corrupt presidential pressure, or rotate early primary election dates among all states – or to fix any other glaring flaw in our system – is through CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT. Without amendments, even the fixes that a functioning Congress could do by regular statute (with Court support) are impossible. And for several problems like the risks and harms imposed by the Electoral College for US presidential elections, term limits or age limits in Congress and the courts, representation in Congress for residents of Washington, D.C., and limits on corporate influence via election spending, only constitutional change could fix the problem. As Joseph Fishkin and William Forbarth argue, we have to make pro-democracy reform “constitutional again” –including fixes to misinterpretations of First Amendment free speech rights.

The Plan Laid Out in The Democracy Amendments. Many people are afraid of even talking about constitutional change – as if we had any easier option, or as if apocalyptic amendments could somehow get ratified by three-quarters of the states. They forget the history of the Progressive Era when popular demands forced Congress to pass amendments that made the Senate more responsive, expanded the vote to women, and reduced economic inequality. A century later, without new amendments, a small elite will extract ever larger gains while the rest of our households stagnate.

Ziblatt and Levitsky arrive at the same conclusion: they propose 15 briefly stated different amendments to address some of the breakdowns I have mentioned. But in addition to their helpful historical and international comparisons, we need a more detailed plan to fix all the problems noted above, and more. The Democracy Amendments lays out such a constitutionally nuanced agenda in 25 amendments formulated to draw support from across the political spectrum in the United States. For example, it explains how to limit lobbying by businesses, cap campaign donations and “independent” election spending by billionaires, fix gerrymandering in a way that promotes more competitive seats (rather than only proportional outcomes), criminalize long trains of lies by high federal officials and candidates for office, create a viable impeachment process, and rotate the early primary elections between states starting no earlier than March.

Unlike the Progressive Era, however, today’s Congress is heavily influenced by powerful special interests working through SuperPACs, and dark money funneled through many shadowy groups spending on elections. It is even more heavily controlled by the extreme wings of party bases, given our outdated primary system. As a result, it is very unlikely to pass any significant amendments by the required two-thirds majorities. Even no-brainer amendments – such as allowing naturalized immigrants to serve as President or prohibiting the President from pardoning someone who might otherwise make a plea deal and testify against them in a criminal trial – probably cannot pass Congress in its current diminished form. Or at least not without some dramatic new incentives.

This means that the only promising legal option left to repair the American government is to call a new constitutional convention that can send proposed amendments directly to the states for ratification without them first passing Congress. This is probably now the only way to save the US from a slide towards despotism that could crippled the NATO alliance and eventually hand global control to mass-murdering tyrants in China and Russia. This extraordinary convention option – which could bring together people as politically far apart as Larry Lessig and Greg Abbott – might also motivate even today’s Congress to pass a few bipartisan and salutary amendments on to the states for ratification (as it did in 1916 when the popular momentum building to call a new convention finally moved the Senate to pass an amendment for direct election of senators). The prospect of a new national convention meeting would also propel far greater public interest in statehouse elections too.

A National Constitutional Convention is the best way to pass these Democracy Amendments. The Article V option to call a new constitutional convention has never been used – which certainly would have surprised many of the leading founders, including Madison, Jefferson, George Mason, and Hamilton (who touted its potential in Federalist 85). But the time to use this emergency escape door has come, because a national convention offers several key advantages as a way to get around permanent obstacles in Congress:

If well-structured, a convention can consider multiple possible amendments at once, and forge new compromises or grand bargains to get the country out of its current rut (although there are debates about an open agenda that I address in the book).

A national convention can pass amendments by a simple majority vote in one body, as opposed to two-thirds (67%) of each chamber of Congress voting separately, when sending proposed amendments to the states.

When a new convention is planned, this prospect will inspire wide-ranging national conversations and focus discussions in high schools, colleges, and many local forums on constitutional topics, which will improve citizens’ understanding.

A convention can provide a positive way for people to channel their deep frustrations and anger at dysfunction in the federal government as a whole.

Congress can specify that federal and state government officials cannot serve as convention delegates. In structuring a convention, they should also compromise by allocating between one and five delegates per state based on relative population sizes, and allow the convention to pass amendment proposals by either a majority of delegations or by two-fifths (60%) of delegates.

Imagine that each delegate can also bring along one non-voting expert as advisor. A convention could then bring some of the best political minds of our time together under a call to transcend party politics, and do an end-run around the big lobby groups that control D.C.

Convention delegates, with historical reputations at stake, would be under great pressure to come up with innovative solutions and to produce substantive results that could be ratified.

Congress can probably call a new national convention at any time; but two-thirds of the states together can also force Congress to call such a convention. Depending on how the House and/or Senate Judiciary Committee(s) decides to count, it seems that a sizeable proportion of the 34 required states have already passed unrescinded resolutions to call a convention. If the House committee, led by Jim Jordan and Jerry Nadler, ever addresses the issue, it would doubtless spark serious discussion of the convention idea in more state capitols, as well as one social media. Some state governments might even put the issue of a convention to voters as a ballot question.

Crucially, A CONVENTION CANNOT ENACT ANY AMENDMENT BY ITSELF; ratification by three-quarters of the states – the highest threshold in any established democracy on the planet – will still be required until this threshold is lowered by another amendment (or even eliminated, as Levitsky and Ziblatt propose).

This last point should help to reassure skeptical members of the public: amendments emerging from a convention would still have to be ratified by 38 states to become law. No one is going to propose deleting the Bill of Rights, and the Civil War amendments are safe. Nor would a new convention attempt to rewrite the entire constitution: delegates would know that such a “complete overhaul” could never be ratified by even half the states, let alone three-quarters.

Here are two further suggestions that would help a convention succeed. In a new statute enabling the convention process, Congress could provide that convention delegates must be elected but cannot be current or recent employees of either the federal government or state governments. They should instead be civic leaders of many kinds, and bound not to take a political job or lobbyist position for at least a decade after the convention. Yet even without such a restriction that would promote public trust in them, the delegates could hardly avoid thinking of founders such as Washington, Madison, Hamilton, Sherman, Mason, Wilson, and others who served in the 1787 convention. They would inevitably feel a great responsibility to produce positive results for their children and generations to come. How could they emerge from a convention empty-handed and face their own families, much less the broader public?

Second, especially in a closed-door convention, compromises could be hammered out that both address the fundamental problems behind US government failures, and stand a real chance of ratification. To that end, in the enabling law, Congress should specify an open agenda, blocking unjust attempts by some self-serving state officials to hamstring a convention in advance so that it only considers their pet proposals. The original convention rightly ignored instructions that tried to limit its agenda. By preserving its free deliberative function, convention delegates were able to address (albeit not totally solve) most of the hardest problems they recognized at the time.

This is another reason why we need liberals as well as conservatives to engage on getting the plan for a new convention right, rather than hamstringing the process in ways that doom it to failure. It is fine for Congress to mandate, in the enabling statute, that the convention must consider issues raised in the various state calls for a convention. But it would be disastrous for the law to specify that a new convention can consider only these issues (and if Congress absurdly demands that exactly the same issues must be specified in 34 or more state calls, a convention will never be called). Only with an open agenda and plenary authority like that of the original convention, the new delegates can have the flexibility need to reach productive compromises.

For example, imagine an amendment eliminating the Electoral College combined with a moderate version of the balanced budget requirement that fiscal conservatives have long sought. Constitutional limits on campaign contributions and lobbying might get paired with some modest term limits that some right-wing state legislators want to see placed on members of Congress (though not, notably, on themselves). Another amendment might establish a federal right to vote, uniform automatic voter registration, and national vote-counting procedures, along with modest anti-fraud provisions such as double-counting of all ballots – all to be specified in federal statute. Amendment ideas can be combined and “logrolled” like other less extraordinary legislation.

Similarly, an amendment banning the filibuster could be combined with a clause weakening the power of Congressional leaders to kill or stall legislation. It could allow 45% of the House or the Senate to bring two or three bipartisan bills per term to final votes by signed petition. If this amendment were ratified, the gridlock that has gripped Congress for decades would be broken, and people would start to learn what works and what doesn’t from seeing their party’s agenda get enacted – for better or worse – when they win elections. This effectiveness would motivate more young Americans to engage and encourage better candidates to run. Direct election of the President would further increase turnout, given how close our popular votes have been: every state would become a “swing state.”

Thus a new convention could build trust and goodwill by harvesting constitutional “low-hanging fruit,” such as a ban on gerrymandering for political advantage in all federal and state government districts, and a measure to fix the number of Supreme Court justices at nine with staggered 18-year terms (rather than expanding the court). Both would be popular across the political spectrum, as would limits on the presidential pardon power and bans on departing lawmakers going to work for lobbies or industries that their votes directly and materially benefitted to the tune of millions. Once the public understands that we can make progress through amendment, it may even become feasible to break up large states or address the worst problem in our system, namely state equality in the Senate, in other creative ways – such as by limiting the Senate’s power to block House-approved bills indefinitely.

There could also be some harder bargains. For example, an amendment to give Washington D.C. representation in Congress as if it were a state (which passed Congress in 1978 but included a questionable seven-year time-horizon for ratification) could be combined with (say) a provision allowing two-thirds of state governments, acting together during any two calendar years, to rescind a federal law. An amendment to overturn the Citizen United ruling that unleashed independent election spending by corporations could by combined, perhaps, with a statement of corporate rights. Many such compromises are imaginable; but the immediate goal is to get the constitutional reform bandwagon rolling, so people see some real prospect of fundamental change brought about legally, rather than by populist radicals willing to break laws and corrupt the government to get their way.

Much of the silent middle of the country will probably start to get more engaged when it becomes clear that a new national convention really is likely to meet. A broad-tent centrist movement focused on making this process work might well prove too fast and powerful for monied lobbies to defeat. They are used to blocking statutory proposals in Congress one by one, not to bending an entire convention of non-politician delegates to do their bidding. People want reasons to hope, and this is now likely to be the most viable remaining way to give them that hope. The prospect of a convention can give the great frustrations that have built up a productive outlet, channeling that motivation into a positive project, rather than more handwringing over our political situation, combined with blaming and vilifying the other side. Let’s try something constructive instead. At this point, we have little to lose, and everything to gain.

“No one is going to propose deleting the Bill of Rights, and the Civil War amendments are safe.”

I’m not sure where your confidence in this comes from. I think it’s enormously likely that amendments would be posed weakening both. I’m not saying they’d pass, but I’d be astonished if they weren’t proposed.

LikeLike

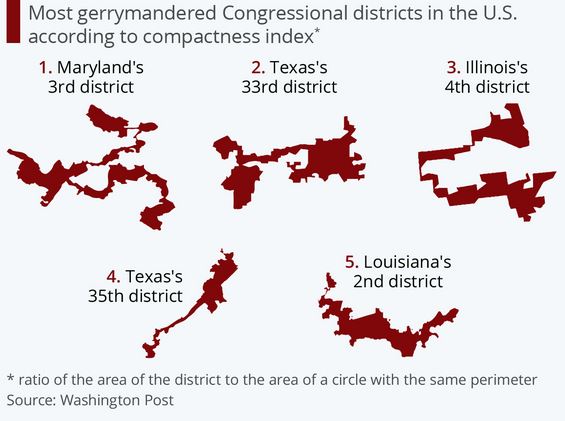

My favorite is the map:

“According to the compactness index…”

A compactness index? What’s that?

Looks at the bottom of the map. Oh. Oh, I see…

LikeLike

Regime change has worked out great in the past for America. I’m not sure why you think it would work so easily and well in Venezuela? Why not adopt a more sensible strategy that does not involve sanctioning a country into economic abyss and hence reducing the need for people to mass migrate?

LikeLike

Is it realistic to think that we can generate adequate motivation to call a constitutional convention for the purpose of “saving democracy” (or something like this)? What makes more sense to me (and has more historical precedent) is generating motivation to call a convention to pass specific amendments that address particular elements of intense, general public concern. Yes, there are motivations, across different political parties and persuasions to “do something, make changes, before the country goes to hell.” There is a sense that “things are coming apart” both culturally and institutionally. And the American pastime of reflexively bitching about stupid or oppressive government is alive and well. But much of this is performative and, in any case, the degree of disagreement across groups and ideological factions is pretty profound. Herding all of the doom-scrolling cats in the direction of an open-ended, problem-solving constitutional convention seems like a tall order. Though the comparison to present partisan and quasi-sectarian rancor is far from perfect, imagine if we had tried to settle the slavery issue (and avoid civil war) by calling a constitutional convention!

If the primary problem to be addressed is partisan and quasi-sectarian rancor, that problem is more cultural than institutional (let alone Constitutional-institutional). Certain constitutional changes would probably help, but, due to the divisiveness problem itself, they are unlikely to get off the ground. And it seems likely that the most important levers for change are largely cultural and ethical (we need to be better people and, at a certain point, that is just up to us). Additionally, many effective institutional levers do not concern changing how the federal government operates (e.g., changing the legal rules regarding, and our attitudes toward and use of, social media might reduce our out-grouping and in-fighting). Finally, there is perhaps no substitute for crises and external threats for bringing a country together. Maybe, however unfortunately, it is just overwhelmingly likely that we will keep fighting with each other until something like this happens? Addressing more specific problems by calling for specific amendments (e.g., some kind of balanced budget or basic fiscal responsibility amendment) seems much more promising.

Is the particular version of a general, let’s-fix-things motivation you are pushing viable? As “fixing democracy” (on specific sorts of pretty ideal models) is mainly a left-of-center thing, I’m not sure this framing can harness general dissatisfaction with how things are going in the country (the sense that we are “coming apart,” etc.). If the center-left (and center-right) had framed the events surrounding Jan. 6 in terms of the specific, damning details about Trump and his actions — instead of focusing on the riot and repeating the word ‘insurrection’ over and over — they might have helped shape the general concerns into concerns about democracy specifically. But they blew it. So, whatever the virtues of it, the prospects don’t seem that good for transforming concern about things coming apart for the country into concern about democracy. The potentially viable general motivation here (one that might plausibly be drummed-up given the materials we are starting with) is further to the political right and less centered on elite or academic concerns about democracy. There is probably some viable pro-democracy narrative-shaping or motivation-steering to do here, but I don’t think you have hit on it.

With a different culture, I think an open-ended, problem-solving, antiquated-elements-expunging constitutional convention would be a great idea. This hints at another problem I have with your program: though the causation is complicated and goes both ways, I think that, in many respects that matter, moral culture comes before institutions not the other way around. As Richard Hanania seems to think that woke culture is a function of flawed civil rights law, you seem to think that various culture-driven phenomena are a function of a flawed Constitution. Though I largely agree, in both cases, that the putative flaws are indeed flaws, count me skeptical of both causal claims. Appeal to a false or too-simple general pattern won’t work and evidence for institutional priority in the specific cases is pretty thin.

LikeLike

I agree that we need an Article V Convention. All current convention calls have and will fail since there are not thirty-four states that will support any partisan call. The only way it will happen is if thirty-four states pass an issue-neutral call which includes a framework for running the convention.

The important thing that must be kept in mind is that a convention must be called. Partisan issues can be debated and voted on once a convention is held.

onlywayto34.com

LikeLike

Pingback: Anarchy, Democracy, and Privacy | Policy of Truth