A masochist, as we all know, is a person who gets perverse satisfaction out of the infliction on himself of what he regards as painful. A literary masochist is one whose pain fetish attaches to published pieces of writing. In general, literary masochism manifests itself as the compulsive desire to read and re-read books that one hates, or loves to hate, simply in order to have the perverse pleasure of doing so: some books are so bad that they hurt so good. The orgasmic climax, the ne plus ultra, of the literary-masochistic experience for me is Ayn Rand’s The Romantic Manifesto, a book I hate with a passion that I find, well, painful. Precisely for that reason, I keep Ro Mo by my bedside (actually, I sleep on the floor), reading it with the sick compulsiveness of an insomniac Anastasia Steele.

There’s nothing worse than reading a terrible book for thirty years and suddenly realizing that there’s a passage in it that you’ve profoundly misconstrued about as often as you’ve read it. Like this one, from the Introduction:

It has been said and written by many commentators that the atmosphere of the Western world before World War I is incommunicable to those who have not lived in that period. I used to wonder how men could say it, know it, yet give it up–until I observed more closely the men of my own and the preceding generations. They had given it up and, along with it, they had given up everything that makes life worth living: conviction, purpose, values, future. They were drained, embittered hulks whimpering occasionally about the hopelessness of life (p. vii).

It’s taken me thirty years and several dozen readings to realize that “hulks” is probably a misprint for “husks.” Consequently, I’ve been reading the damn thing as “hulks” this whole time–three fucking decades–and imagining that Rand thought that the London, Paris, Vienna, Berlin, and St. Petersburg of the early 1900s were populated by clinically depressed versions of Lou Ferigno. When what I was supposed to be picturing were bipedal, discursive, but clinically depressed dry outer leaf coverings discarded after harvest.

Just thought I’d pass that tidbit on, in case anyone felt the inclination to forward it to the Royal Society, or at least the Ayn Rand Society. At any rate, be prepared in the near future (whatever that means on this blog) for some random posts from me on Ayn Rand’s critique of “Naturalism”–which I find fascinatingly and addictively ridiculous. I guess I’m making the assumption that the people who (regularly) read this blog are as into pain as I am. You know who you are. And you know you’ll be back. Guilty pleasures are hard to resist.

Take this self-test if you’d like to earn a free certificate in Objectivist aesthetics:

Fill in the blank:

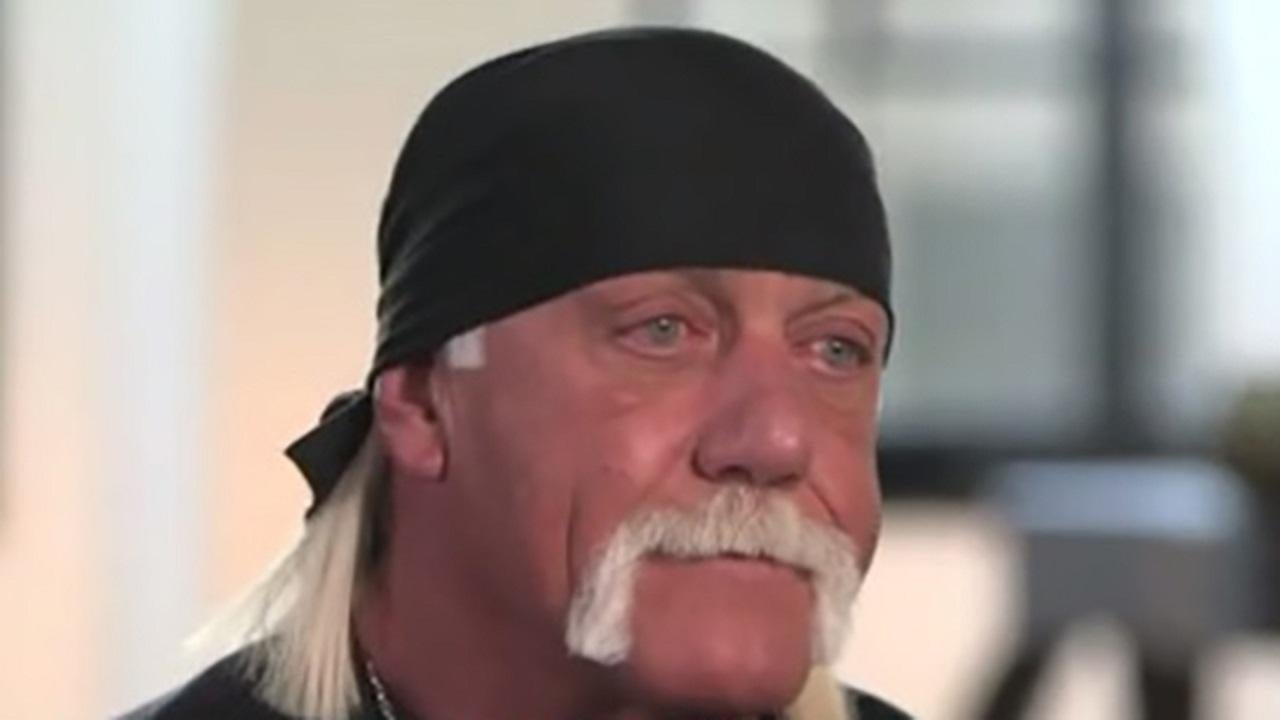

- The preceding photo depicts a drained, embittered ________________________ whimpering occasionally about the hopelessness of (his) life.

“Husk” seems to fit better. “Husk” per the Urban Dictionary is “A person who has no substance, personality, character or knowledge. An empty shell of a human.”

However, a corn husk (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Husk) is not a corn stalk.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You’re absolutely right on both points. I don’t know how, after a lifetime of eating corn-on-the-cob, I’ve managed to confuse husks with stalks. But I have.

It doesn’t work.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Clearly, you are not from the Midwest. The Incredible Stalk would be a nifty anti-hero or super-hero send-up. But, uh-oh, now maybe I’ve wandered from the Romanticist path (and into the Pit of the Irrational)? Commence vehement denunciations in three, two, one…

LikeLike

Well, I did go to grad school in Indiana. But the closest thing to corn in South Bend was the ethanol plant.

I think a bigger problem for “The Incredible Stalk” might be legal rather than aesthetic, since it sounds a bit like someone who goes around stalking people. Though I suppose it depends who he (or she) stalks.

LikeLike

LikeLike

The (rather Moorcockian) Stalker comic was a childhood favourite of mine. Though it only ran for four issues. (DC brought the character back a few times, decades later, but generally unrecognisably.)

That tag line “man with the stolen soul” always bugged me as a kid. His soul has been stolen. So he’s not with it, he’s without it.

Of course we do say “man with a missing leg,” etc. But should we? I think the correct phrase should be “man with a leg missing” ….

LikeLike

“Jack and the Beanstalk” appeared as “The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean” in 1734. “The Incredible Stalk” is shorter than both.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Wikipedia page says, “Husking of corn is the process of removing its outer layers.”

“Dehusking” or “unhusking” fits better. Putting on a dress is “dressing”; taking it off is “undressing.” The English language is sometimes funny. German is funnier. https://ohgodmywifeisgerman.com/guests/the-awful-german-language-by-mark-twain/

LikeLiked by 1 person

To think that Jimmy Wales, a graduate of IU Bloomington, would allow such a thing on his site…

LikeLike

He’s also a graduate of Auburn!

LikeLike

While I admit that “husk” fits somewhat better, it’s possible that she did mean “hulk” in the (metaphorical) sense of “A non-functional but floating ship, usually stripped of rigging and equipment, and often put to other uses such as storage or accommodation” — which is older than the comparatively recent sense of a large musclebound person.

There’s also an even older meaning of “hulk” as “something hollowed out,” from which the above nautical sense is apparently derived. It survives in the (rare, but still in use) verb form “to hulk” something, meaning to hollow it out.

The term’s evolution seems to have been from:

something-hollowed-out

to

ship-stripped-of-equipment

to

no-longer-navigable-ship

to

large-thing-hard-to-maneuver

to

large-clumsy-and-ungainly-person-animal-or-thing

all the way to

large-musclebound-person.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Roderick for the hermeneutical win. So I guess she was talking about the whimpering Temeraires of the mind, “tugged to their last berth to be broken up.”

[There was supposed to be a clever JPG of Turner’s “Fighting Temeraire” here, but it didn’t work, so never mind. Fucking WordPress.]

I guess I was thinking that a husk can be blown about by the wind, lacking an internal source of resistance. But a hulk at sea is a better metaphor for moral drift.

The only safe inference here is that it wasn’t “hunks.”

Any thoughts on which hulk/husks she had in mind? I thought reflexively of Mises, not that I think of him as a whimpering hulk (or husk–or hunk), but she might have. Alexander Kerensky?

By the way, speaking of hunks, I’m sure that any minute now, Sciabarra will swoop in with his “dialectical” answer, and say that based on her college transcripts, Rand must have been referring to N.O. Lossky. And then some rube will demand a “definition per genus et differentiam” of “dialectic.” I’ll bet my paycheck on it.

LikeLike

Of course the final stages of that etymological transition were facilitated by the comic-book Hulk (1962), who followed in the massive lumbering footsteps of vaguely similar comic-book characters named the Heap (1942) and the Thing (1961).

On another note, I like The Romantic Manifesto more than you do. Though with serious reservations. In a recent video I described it (along with her Art of Fiction) as (something like) “a mixture of wisdom and folly” and “a mixture of insight and refusal of insight.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

So I’m going to respond to both Roderick and Chris here, hopefully without writing a counter-Manifesto to Ro Mo.

To get one thing out of the way: I put both The Art of Fiction and The Art of Non-Fiction in a different category from Romantic Manifesto. Both of the preceding books were, to me at least, pleasant surprises, but that’s partly because they have a much narrower scope and more limited ambition than Romantic Manifesto. Art of Fiction is about fiction, full stop. Really, it might have been called The Art of the Novel. It has some interesting things to say about fiction, and offers some useful insight into particular books. I was pleasantly surprised by her praise for Isak Dinesen. I reject most of what she says about style, and most of what she says about tragedy, but fine–let’s just chalk that up to ordinary disagreement.

Romantic Manifesto is supposedly about art, but is also–by the way–supposed to be a systematic discussion of the nature of psycho-epistemology. It’s supposed to be a contribution to aesthetics and depth psychology all at once. So we’re talking vaulting ambition here. But by that standard, the standard set by its own ambitions, it’s an obvious failure.

For years, I held the view of RM that Chris articulates below: I used to think that while I agreed with her general view of art and its function in human life, I disagreed with her particular recommendations and/or disrecommendations, i.e., her tendency to conflate her tastes into basic aesthetic principles. It was Kirsti Minsaas who challenged the coherence or plausibility of such a view to me in conversation: is it really possible to espouse Rand’s principles but systematically reject the way she deals with concretes in a certain domain?

At first, I thought: sure, why not? I could come to the same principles by way of my own approach to my own set of concretes. And I suppose that’s possible in principle, but I don’t think it happens to be true here. Anyone who holds that view has to ask: what went wrong with Rand’s thinking that she managed to arrive at true aesthetic principles on the basis of such a jaundiced, skewed view of the concretes? I ended up thinking that the problems were far more systematic than I had previously realized. In fact, I’ve come to think that that’s generally true of Objectivism.

After re-reading Romantic Manifesto several times, once for a mini-seminar I did with Fred Seddon and Glenn Fletcher a couple of years ago, I came to a much more negative conclusion. The general aesthetic principles of the book all rest on Rand’s depth psychology, her account of “sense of life,” and so on, which is meant to be an alternative to Freudian depth psychology and Skinnerian behaviorism. But I think Rand’s views are at least as confused as either Freud’s or Skinner’s. (I think of myself as a neo-Freudian.) By implication, so is her aesthetics, at least as a systematic set of principles.

One problem is that it’s not even clear what Rand intends to do in the book. In the Introduction, she claims to be offering “the base of a rational esthetics” (p. vi). By the middle of “Art and Sense of Life,” she seems to be punting on that ambition. There she says that the universal principles that apply to “all art…are outside the scope of this discussion” (p. 42). I’ve never been sure whether the referent of “this” is “this essay” or “this book.” But if it’s the latter, the book is a self-avowed failure by its own standards.

Even if we get away from aesthetics, and just treat the book as a philosophical discussion of various branches of art, or even more narrowly, literature, I find it hard to separate the wheat from the chaff and leave the matter there. As she herself says, art is a deeply personal matter. But for that very reason, a person with a modicum of respect for others doesn’t discuss it in the flippant, contempt-laden way she does. She goes out of her way to quote Aristotle’s Poetics, but has nothing of substance to say about tragedy, just a few stray comment-criticisms of Shakespeare and Byron. I mean, come on–that’s not going to fly.

This will be old hat to the Aristotle scholars out there, but compare her comments on tragedy with a pretty standard Aristotelian line on tragedy:

https://iep.utm.edu/aris-poe/

There’s more insight in that one article than in the whole of Rand’s book.

I’d say about the same of her dismissals of Classicism and Naturalism. Her dismissal of Naturalism strikes me as the more philosophically interesting of the two, but also (perhaps for that reason) the more philosophically confused and confusing. In any case, it’s infuriating to read someone talking about what “the Naturalists say” without citing a single one, or about the Naturalist “denial of volition” without giving a single plausible example. It’s especially infuriating if you’re as partial to Naturalist fiction as I happen to be. (Can anyone discuss 20th century Naturalist fiction and ignore both Hemingway and Paul Scott? Ridiculous.)

I promised I wouldn’t write a counter-Manifesto, so I’ll leave it there. I agree that if you ignore the book’s stated ambitions, and read it very charitably, there is intriguing stuff in there. Fair enough.

Perhaps this is a temperamental matter, but personally, I find it difficult to read Rand (or observe the Objectivist “movement”) without feeling a sense of broken promises and betrayal. When I first joined David Kelley’s organization in 1991, it seemed possible to imagine a completely different future for Objectivism than the one that actually occurred. It seemed possible to imagine an Objectivist movement that articulated a left-libertarian position well in advance of that happening among libertarians. It seemed possible to imagine people making and dealing with some of the criticisms I’ve just made above, and others like them. Etc.

None of that happened, and in retrospect, it seems obvious to me that Rand’s works provide the explanation why it didn’t happen. In order to carry Rand’s project forward as real philosophy, you’d have to repudiate the way she did philosophy tout court. You’d have to say out loud that philosophy cannot be done that way–as an exercise in well poisoning, histrionic rhetoric, handwaving, crowd-pleasing, and narrow political activism. It took me way, way too long to figure out that no one within organized Objectivism wanted to hear that, not even on the IOS/tolerationist side.

Hence my love-hate relationship with all of Rand’s work. For me, her works don’t just combine wisdom and folly (though they do), but promise and betrayal.

LikeLike

“Romantic Manifesto is supposedly about art, but is also–by the way–supposed to be a systematic discussion of the nature of psycho-epistemology.”

On that note, do you have the later edition of RM that includes the essay “Art and Cognition,” or the early edition that didn’t have it yet?

“Art of Fiction is about fiction, full stop. Really, it might have been called The Art of the Novel.”

Well, The Romantic Manifesto is subtitled “A Philosophy of Literature,” which seems to suggest a similar delimitation. (It’s not as though she has much to say about, e.g. poetry. Of course she does talk about drama.) Though some of the essays in the book do range over artworks more broadly — painting, sculpture, music — which makes the subtitle a bit of a mystery.

Among the book’s biggest failings, for me, are precisely her discussions of the non-literary artistic genres that her subtitle suggests are not part of her topic. For example:

a) She says she doesn’t have a worked-out theory of music, but then she proceeds to issue decisive judgments as though she had one.

b) Her sweeping condemnation of abstract art is at odds with her much more reasonable treatment, in The Fountainhead, of architecture, which is abstract art if anything is. (IIRC, Torres and Kamhi, in What Art Is, report that Rand in later life retreated from her earlier view that architecture was a genuine art, in part because it had a partly utilitarian purpose and in part because she couldn’t see how architecture counted as a selective re-creation of reality — as though she’d completely forgotten, or betrayed, what she wrote in The Fountainhead. Of course Torres and Kamhi cheerfully double down on this reversal, tossing Roark and Cameron, along with Wright and Sullivan, under the bus.)

Of course music is abstract art too, and how it represents a selective re-creation of reality is a longstanding puzzle (though many Randians take the line that it represents the human voice — but that can hardly be the whole story — and Rand in “Art and Cognition” gives her Helmholtzian integrable-mathematical-relationships line, though that can hardly be the whole story either), but at least she was never crazy enough to downgrade music as an artform — music was always of central emotional importance to her, maybe even more than literature (judging from what she wrote about music IN her literature).

For that matter, in an early draft of We the Living, Rand seems to have felt more appreciation for the expressive possibilities of abstract painting than she did when, in more dogmatic mode, she wrote RM:

“The shelves were bright with white covers and red letters, white letters and red covers—on cheap, brownish paper and with laughing, defiant broken lines and circles cutting triangles, and triangles splitting squares, the new art coming through some crack in the impenetrable barrier, from the new world beyond the borders ….”

As I’ve speculated elsewhere: in the Soviet Union abstract art was associated with foreign capitalism, while in the u.s. it was associated with leftism, so maybe her shift in position was unduly influenced by the relevant ideological associations? Though in general she was happy to embrace writers (e.g. Hugo, Dostoyevsky) whose ideologies were quite different from her own, so I dunno.

“I’ve never been sure whether the referent of ‘this’ is ‘this essay’ or ‘this book.’”

Well, the book is a collection of previously-published essays, so that line may have been in the original essay, in which case it would seem to be just about the essay. I don’t have my bound collection of The Objectivist handy to look. (A feature of my life seems to be that I have hardly any of my possessions handy. Full atrium and empty hands, to paraphrase Plato.)

I’m reminded: I heard Elaine Pagels lecture on “The Gnostic Gospels” a few decades ago. (Was it in Chapel Hill or here in Auburn? I think it was here.) Some Bible-thumper in the audience quoted at her the closing lines of the Bible: “I testify unto every man that heareth the words of the prophecy of this book, if any man shall add unto these things, God shall add unto him the plagues that are written in this book: and if any man shall take away from the words of the book of this prophecy, God shall take away his part out of the book of life,” etc. (Revelation 22:18-19) — the implication being that anyone who tries to introduce new texts into “the” canonical Bible (as though there were just one — as though Jews, Catholics, Protestants, Eastern Orthodox, Slavonic Christians, etc. don’t all have different versions of which books and/or passages are in the Bible, even without getting into more exotic options like the Gnostics and the Coptics — but anyway:) was risking divine wrath. Pagels reminded him that at the time Revelation was written it hadn’t yet been incorporated into the Bible, and so “this book” could only mean Revelation, and not the Bible itself. (I’m mischievously tempted to wonder, further, whether incorporating Revelation into the Bible doesn’t itself violate the prohibition on “adding unto these things.”)

“I’d say about the same of her dismissals of Classicism and Naturalism.”

Yeah, as I said — her reasons for disliking what she dislikes are crap. (And how she can condemn tragedy after writing We the Living is a mystery. Plus many of her favourite plays and novels are in fact tragedies.) But she makes a much better case for liking the things she likes, and I’m grateful to her both for introducing me to Hugo, Schiller, Rostand, Rattigan, etc. (all tragedians incidentally!!! go figure), and for giving me a lens through which to appreciate their works more deeply and complexly than I otherwise might have.

“or about the Naturalist “denial of volition” without giving a single plausible example.”

I suspect she may have had in mind Dreiser’s novels Sister Carrie and An American Tragedy, in both of which a central character sort of stumbles their way almost accidentally into committing a crime (theft in the former, murder in the latter) without ever making a conscious choice to do so, as though it were really the immediate circumstances rather than the person’s mind and will that are responsible for the act. (Though it’s a bit awkward for Rand that Hugo in Les Miserables describes Jean Valjean’s theft of a coin from Petit Gervais in rather similar terms.)

“For me, her works don’t just combine wisdom and folly (though they do), but promise and betrayal.”

I guess that’s true for me too, to some extent. While I was never a full-fledged Objectivist, I was once much more heavily Objectivist than I am now — strongly devoted to both her fiction and nonfiction. Even apart from doctrine, though, I always had too much sense of humour to be an acolyte — as when, while still pretty much a Randian, I wrote a Rand parody about a narcissistic hero named Ripslash Goldklanger who went into reveries about the rational productive process that had led to the invention of the elevator (and as a side note, the invention of the skyscraper, just to hold the elevator) EVERY time he stepped into an elevator to go to or from his office or penthouse, thousands and thousands of times. The villain of my story, by the way, was a perfectly inoffensive guy whom fate had saddled with the name Mushy Turd. (Where is that parody now? Stored inaccessibly in some box, presumably — in my atrium but not ready to hand. A continuing frustration. As I may have mentioned.)

Amyway, even in college, during the height of my Randian phase, I always felt dissatisfaction at the hostile and dismissive attitude that Rand and her acolytes cultivated to all outside the pale. I was certainly highly enthusiastic for all things Randian. But I was reading Rand’s (and Peikoff’s) denunciations of analytic philosophy as worthless crap even as I was simultaneously studying actual analytic philosophy with great appreciation. Or again, I would read a review in ERGO (the then-MIT-based Objectivist student newspaper I used to write for and deliver) about how no one could possibly like Threepenny Opera for the music, when I’d just seen the same performance of Threepenny Opera that was being reviewed and had been blown away by the music. And I recall one time at ERGO, after I’d made a joke about being a Kantian (I wasn’t), one of the staff said to me “you shouldn’t make jokes about being a Kantian; I know you hate Kant, but some of our younger staff might be confused” — and I remember (apart from my annoyance at the invitation to self-censorship) thinking “do I HATE Kant? is that the right word? I disagree with him, but I think he’s fascinating, and I certainly don’t think he was deliberately designing his system so as to attack the human mind or human happiness.” (That said, most of my interactions with ERGO were quite positive. It may have helped blunt the edge of their attraction toward cultishness that they themselves had been denounced by the Randian hierarchy for trying to profit [via their free newspaper, ahem] from Rand’s name and ideas.)

Although it used to bother me that Rand condemned things I liked, it never bothered me enough to make me at all inclined to give them up. And by the time the Kelley break came, I was no longer Randian enough to hitch my wagon too closely to the Kelley star (so it didn’t rock my world when I was eventually denounced by people in Kelley’s orbit — cough :: Rbrt Bdntt :: cough — as a “malevolent tribalist”). So I feel as though I can happily sort the wheat from the chaff in Rand (to cite the imagery I used in the title of my essay “The Winnowing of Ayn Rand”) without feeling a sense of rupture. I mean, Aristotle had sucky views on slaves and women — sucky even by the standards of some of his contemporaries. Oh well.

“When I first joined David Kelley’s organization in 1991, it seemed possible to imagine a completely different future for Objectivism than the one that actually occurred.”

But if you’re looking for a truly more open, lefty, mature version of Objectivism, one more willing to engage with Rand’s flaws — it did happen, as you well know. It’s just that its headquarters weren’t in Poughkeepsie (or, later DC) — let alone in Marina del Rey (or, later, Irvine or Santa Ana). They were (and are) in Brooklyn.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I have the Revised Second Edition of RM (1975), with “Art and Cognition.”

I guess I took the reverse tack to RM‘s subtitle: given its contents, I took the book to be a general discussion of aesthetics, minimizing the subtitle. If you’d pressed me, I might have said that she took literature as the paradigm art form, so that the principles that applied to it applied to the other forms in a derivative way.

I agree with both of your criticisms, (a) and (b)–even if it hadn’t occurred to me to think of architecture or music as “abstract art.” Architecture just struck me as incompatible with her official theory of the nature of art, and music as involving a very uneasy fit.

I think the standard (Objectivist) view of music is that it’s a selective re-creation of reality by way of the images it generates in listeners, on the assumption that music always does generate images in listeners, or at least attentive ones. I’d been inclined to go as far as accepting that music generates images (it did in me, after all) until I met people who told me that they found the claim preposterous. The most vehement critic I ever met with Fred Seddon, who insisted (insists) that if music generates imagery for you, you’re daydreaming rather than listening to it, there’s something wrong with you, and you should (endeavor to) stop. Obviously, I wouldn’t go that far, but even if Rand were right about music’s imagistic capacities, that fact doesn’t really make music a selective re-creation of reality in the relevant sense.

And even if we restrict Rand’s thesis about abstract art to abstract painting, the thesis just seems like dogmatism to me, with no real reason given why we should accept it to the detriment of non-representational painting.

On the referent of “this: either the “this” is about the essay, or it’s about the book. If it’s about the essay, she’s contradicting what she said in the Introduction. But if it’s about the book, then I guess I’d just ask, “Where in the book is there a discussion of the general, universal principles of aesthetics that guide the evaluation of aesthetic objects?” I don’t think the question has a straightforward answer. It’s not really the question the book aims to answer (insofar as it aims to answer a single overarching question, which is itself unclear).

On adding works to the canon, I think the relevant principle is that a work permissibly can be added to the canon if it can be expected to bring a revenue stream to ARI, the Estate of Ayn Rand, and/or associated corporate entities. Otherwise, it’s apocryphal.

My version of mischief is to point out that Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology is an introduction to a book of epistemology imagined but never actually written (at least by Ayn Rand). If “Objectivism” consists of the works of Ayn Rand (as per ARI doctrine), it follows that Objectivism lacks an epistemology. Indeed, since words are required to complete thoughts (on Rand’s view), a whole unwritten theory would appear to be a contradiction in terms. In that case, IOE is an introduction to a non-existent theory. Which raises the question: can you really introduce something that doesn’t exist?

On the case she makes for liking what she likes: I wonder if you’re being overly charitable to her. Does she really make a case for Hugo, Schiller, Rostand, or Rattigan? Granted, she discusses Hugo at length (and makes an extended case for at least one of his novels), but Schiller and Rostand each get one passing reference in RM, and Rattigan isn’t mentioned at all.

In the latter three cases, I think it’s more plausible to say that one is intrigued to come across them in Randian contexts, then inspired to pursue them, and then retrospectively sees why she might have liked them. But in that case, it’s the reader that’s doing the work, not Rand. Hugo is a different story, but it’s not clear to me that Rand’s case would persuade a reader agnostic about Hugo to read him. And in any case, finding a literally agnostic reader might be hard to do, given the widespread popularity of Les Miserables and The Hunchback of Notre Dame. I encountered Hugo before I encountered Rand, so it’s hard for me to say one way or the other. That said, I read Ninety-Three as a direct result of reading RM, so I was probably influenced by her there.

Your Ripslash Goldklanger parody reminds me that in tenth grade, an English teacher gave us the assignment of writing a satire. Without ever having read it, I decided to write a satire of Rand’s Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal, ascribing to it every capitalist cliche I could think of, and making her the head plutocrat of some capitalist enterprise. I got an “A” on the paper. Years later, on actually reading Capitalism, it occurred to me that I hadn’t done a bad job of guessing what was in it.

Unfortunately, though, by my late college years (call it the early 1990s), I had become a sort of eccentric/heterodox true believer in Objectivism. My method was to retain a ferocious adherence to a version of Objectivism that kept getting defined and re-defined in terms of ever higher-order theses, jettisoning all the “vulgar” claims of Objectivism until I managed to generate a version of Objectivism recognizable as Objectivism only to one person: me. For years, I was absolutely convinced that this approach (and only this one) combined analytic rigor with political moderation. As I’m sure you already know, this Eduard Bernstein-inspired approach to Objectivism failed ca. 2013, when it became plainly apparent to me that there’s no feasible way to become the Eduard Bernstein of a movement populated by an Andrew Bernstein. The old “one Bernstein too many” problem.

I guess one real difference in our Randian trajectories is that I put a great deal more stock in the IOS enterprise than you did. I “became” an Objectivist a few months after the Kelley-Peikoff split, with no real sense that a split had taken place, or what it was about. I “aligned” myself with Kelley mostly because his seminar was nearby, and was cheap and easy to get to. And people at IHS had recommended Kelley as well. My inculcation into Objectivism was really a Kelley-driven phenomenon; before I met him, I was lukewarm about it. He was the one who convinced me that there was more to it than I’d realized. And early on, he was a spellbinding and inspiring speaker. The early IOS Seminars, call it 1991-1994, left a lasting mark on me. But after the mid to late 90s, it lost its appeal, and certainly by the 2000s, the thrill was gone.

But I certainly agree: as far as I’m concerned, Rand Headquarters is now located in Gravesend, Brooklyn. I’m persona non grata at all the other ones.

LikeLike

There’s a passage in John Gardner’s “October Light” where a character considers what images go with the French horn piece he’s listening to:

“… he’d tried various ideas: the idea that the image was of threatening apes, harmless ones, small ones, chittering and flapping unbelligerent arms in a brightly lit jungle; the idea that the picture was of children at the beach in sped-up motion. … Then it had come to him as a startling revelation … that the music meant nothing at all but what it was: panting, puffing, comically hurrying French horns.”

Actually, that passage is virtually the only thing I remember from “October Light”; the rest of the book is mostly a blank. But then I was like 14 when last I read it.

LikeLike

The only novel I’ve read by a Rand-influenced writer (in the narrow sense of one who was part of her circle) is Erika Holzer’s An Eye for an Eye, which later became a major film with Sally Field and Kiefer Sutherland. The book had an anti-vigilante theme–and was lauded for its anti-anarchist overtones in Objectivist circles. The movie, naturally, takes exactly the opposite tack, at least on vigilantism.

I didn’t have a strong positive or negative reaction to the book, so I suspect that’s why I never read any of the other Randian novelists. I haven’t heard Smith’s talk.

Yes, I remember Rattigan’s being mentioned in one of the Objectivist newsletters. I once had the whole complement of them from beginning to end, but either misplaced or lost them in my last move.

But I guess my point is sort of the reverse, or perhaps the flip side, of the one you make in the opening 20 minutes or so of your video on Rand’s writing. Yes, one has to be open to what’s of value in her writing, but I also think there’s a tendency to over-read or over-interpret Rand, to have her say things she should have said and could have said, but didn’t actually say.

I was half-joking about the crack I made yesterday re epistemology, but there is a certain truth to it. Rand describes IOE as a “series of articles” presented by popular demand, summarizing one cardinal element of an epistemology which she later intends to systematize in a full treatise, but never did. Is there really such a thing as a worked-out theory presented as a series of articles by popular demand? Is a summary of a single cardinal element of a theory itself a theory? If the theory of concepts is one cardinal element, what are the others? Amazingly, none of the interlocutors in the Appendix asks the obvious question: when is the actual book coming out, and what’s in it? Maybe that would have been rude, but that’s the first question I would have asked. (The next would have been: why should anyone take your framing of the problem of universals as a given?)

That hasn’t stopped ARI-oriented scholars from producing whole volumes with titles like Concepts and their Role in Knowledge: Reflections on Objectivist Epistemology. But what they’re calling “Objectivist epistemology” is their work, not hers. The great irony is that these are the people associated with the outfit that makes “Fact and Value” into a de facto loyalty statement. But the success of their scholarly endeavors relies on systematic, unacknowledged violations of its claims.

I guess I’m less charitable than you to Rand and her followers, because I find the preceding sort of hypocrisy deeply offensive, and think of it as having roots in Rand’s biography and writing. The more charitably she’s read, the harder it becomes to explain the malfeasances of her followers as adherence to the Master’s claims rather than as departures from them. But if they are explained by adherence, we get a more sinister picture of what Objectivism was about from the outset: for all of its insight, Objectivism is a form of propaganda, with all of the worst features of propaganda. One is a tendency to exaggerate what one has a “systematic theory” about when one’s claims raise more questions than they answer. I think of Hilary Putnam’s claim in one of his early writings on philosophy of language that Lenin had a “theory of reference.” He then cobbles together a couple of insights, and voila, history gets re-written: Lenin was a great philosopher of language, predecessor to Kripke.

Come on. No. Lenin-as-philosopher of language is just an expression of Putnam’s enthusiasm for Leninist politics at a certain stage of his career.

I don’t think the Randian tendency is quite as extreme as that, but it’s there: to return to aesthetics, I see more argumentative lacunae in RM than I do actual arguments. I happen to agree with what she says about Liszt, and about the “Blue Danube Waltz,” but it’s not as though she says anything that would have convinced me if I hadn’t come to the table agreeing.

LikeLike

I used to do Rand’s “Thematic Apperception Test” when I taught aesthetics, i.e., had the students listen to maybe ten musical selections, then write down what images, if any, spontaneously popped into their heads. I can’t say I did a systematic study of their responses (I mean, that would have required IRB approval) but in general, most students reported “seeing” images, and the images usually had something in common.

Obviously, there were lots of confounding variables here: the students probably inferred that they were “supposed” to get images, and a lot of the music I used was programmatic music practically designed for that purpose. (I didn’t give the titles.) But I was curious to see how close they’d get, whether to the composer’s intentions or to one another. One selection was Saint-Saens’s “The Swan.”

I was surprised by how often students invoked aquatic imagery.

Another was Joe Satriani’s “Summer Song” (unfamiliar to them before the exercise):

I was surprised by how many students invoked summer, at least in a broad sense (“Walking down the boardwalk at Seaside on a hot day,” etc.)

I once asked Fred Seddon (a huge Beethoven fan) what images he saw when he listened to the Moonlight Sonata. He said, “Somebody playing ‘the Moonlight Sonata.'” What about the first few notes of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony? “An orchestra playing the Fifth Symphony.” When I asked him about the Sixth Symphony, he just stopped me and said I was “cheating.”

LikeLike

“Rattigan isn’t mentioned at all.”

I was thinking of an article on Rattigan in the newsletter, not in RM. But now I see that the article was by Kay Nolte Smith, not by Rand. (Though presumably it had Rand’s approval.)

Smith incidentally strikes me as the most aesthetically successful of the various novelists inspired by Rand, and also the one whose talents seemed to unfold in greater and greater profusion over the course of her all-too-short career. (Of course there’s a certain appropriateness in the fact that in Smith’s first novel, the insidious mentor who ruins the lives of his protégés is based on Ellsworth Toohey, whereas in her much better fourth novel, just four years later, the insidious mentor who ruins the lives of her protégés is based on Rand herself.)

I wish Smith’s excellent 1990s talk “Romanticism, Rand, and Reservations” were published in print form somewhere. It’s very relevant to the issues we’re discussing here. I have an audio cassette of it somewhere (in my atrium but not to hand, again) but who knows whether it’s still in playable shape. Perhaps Chris S. has a copy though. Anyway, *someone* needs at least to digitise that talk and disseminate bootleg copies … not that I would suggest such scofflaw behaviour to anyone among us.

LikeLike

I’ve read Holzer’s Double Crossing and Eye for an Eye; I enjoyed the former more than the latter (despite the howler where she describes, without irony, a would-be defector in the Soviet Union practicing English with a British accent, in case he defected to Britain, and with no accent, in case he defected to America). But not remotely in Smith’s league. (Though, I’d be willing to better, better than Andrew Bernstein’s novels, which I have not inflicted on myself.)

Your dislike of the Blue Danube Waltz is a sign of deep moral corruption, btw.

LikeLike

Oops, I misremembered. It wasn’t R.B. who accused me of “malevolent tribalism,” it was I who accused him of “malevolent tribalism”!! Oopsie. Well, he accused me of plenty else.

LikeLike

Something just occurred to me about this:

Yes to the parenthetical, but what about Peter Keating’s quasi-murder of his colleague in The Fountainhead? (I forget the victim’s name, but I think it was Lucius Heyer.) That “murder” has the same “stumbling” quality that you ascribe to Dreiser (haven’t read Dreiser myself). That said, I’d have to re-read The Fountainhead (or that scene) to be sure, since Rand may well deliberately have written the scene so as to differentiate her way of writing a scene like that from Dreiser’s.

In any case, two novels by one author is a rather unrepresentative sample. She’s talking about a literary school that, by her own account, originates with Shakespeare. She (very) grudgingly accepts Shakespeare’s genius, but doesn’t credit him with any particular psychological insight, and offers a very (very) implausible account of his work that applies, at best, to Shakespeare’s tragedies (I guess the rest of Shakespeare was just crap unworthy of consideration). But if Shakespeare is the fountainhead of Naturalism, surely at some point between Shakespeare and dregs like Dreiser there had to have been some high points? Apart from Sinclair Lewis, she writes as though there really haven’t been any. And given the nature of her critique of Naturalism (“anti-value orientation”), it’s unclear how anyone could have achieved anything of literary value as a Naturalist.

A couple of weeks ago, I happened to re-read Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio for the first time since high school, self-consciously holding it up to Rand’s criticisms as I read it. (Winesburg is Naturalism if anything is.) Some of Rand’s criticisms do apply to it: many of the stories in the book are relatively plotless, even aimless. The main selling point is psychological perceptiveness. But a reader who came on board with most of Rand’s other criticisms of Naturalism would just miss the point of the whole book–and prove blind to the parts of life that the book is about.

When I got back from Barcelona last year, I did the same thing with Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls, which I assume counts as a paradigmatically naturalistic novel. Here, I’d say that literally none of Rand’s criticisms apply. In fact, they strike me as almost completely obtuse. (I know she discusses Hemingway somewhere, but can’t remember where.) For Whom the Bell Tolls is just as great a novel as I remember from when I first read it as a teenager.

One last example: Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet is one of my absolute favorite works of literature (the four novels on which “Jewel in the Crown” was based). Absolutely brilliant writing, obviously naturalistic (almost journalistic) in nature. It’s mind boggling to me that Rand doesn’t say a word about it, but crowns John O’Hara King of the Naturalist Novelists. If RM had been the first book of Rand’s I’d read, I probably would have put it down right there.

Allan Gotthelf told me that he recommended RM to Martha Nussbaum at some point, hoping to get her interested in Rand by that route (i.e., given her interest in philosophy’s connection with literature). He told me with great disappointment that Nussbaum angrily put the book down at the point where Rand discusses “the Hindu dance” in dismissively insulting terms (recall that “the Hindu dance” distorts man’s body, “imparting to it the motions of a reptile”). Allan shook his head in consternation, as though he just couldn’t understand how anyone could be so unfair.

Dude. Would Ayn Rand have read a book that described tiddlywink music as the soundtrack to Romper Room? I doubt it. Not such a puzzle.

LikeLike

Shakespeare as the father of naturalism is an odd view. Hugo incidentally describes Shakespeare as the father of romanticism — which is perhaps also odd, but I think less so.

Have you read Peikoff’s book on drama? His hostility to Shakespeare is enormous, much greater than anything even suggested in Rand. He takes a few misanthropic speeches by some of Shakespeare’s characters (e.g., “what fools these mortals be …”) as representing Shakespeare’s own contempt for humanity.

Ian McKellen has, unsurprisingly, a view of the value of humanity in Shakespeare that I find more plausible than Peikoff’s.

https://aaeblog.com/2018/01/13/self-reasons-and-self-right/

LikeLike

I just listened to the “Blue Danube Waltz.” I hadn’t heard it in years. I liked it. I have no idea why I said I didn’t. Enjoyable video, too.

Renoir’s “Moulin de la Galette” is one of my favorite paintings (5:15). So this was a treat.

Wow, I’m in a hella good mood now. Would you care to dance?

Peikoff’s book, I take it, is “Discovering Great Plays”? No, I haven’t read it. I suspect that my hostility for Peikoff is more intense than his hostility for Shakespeare, so it takes a lot to induce me read him–much less to pay him and read him . That said, $2.99 for the used paperback version is tempting, or would be if I weren’t broke and unemployed, and I’m morbidly curious what he has to say.

LikeLike

My two chief associations with the Blue Danube Waltz are:

a) with 2001:A Space Odyssey, which I saw in a Cinerama theatre during its original run when I was like five — and later on we got the soundtrack album — and I fell in love with all the music from that film [btw, it’s in the Ayn Rand / Erika Holzer review of that film that I first encountered Rand’s hostility the Waltz — I forget the review’s exact words, but something like “annoying twittering”].;

and b) it was a Long family tradition every New Year’s (until recently, when local PBS stations have let me down, though sometimes there’s an online streaming option instead) to watch and listen to the New Year’s concert from the Vienna Musikverein (supplemented by ballet dancers in Schönbrunn palace, and hosted by, for many years, Walter Cronkite, and later, Julie Andrews; I forget who took over after those two); and each performance always concluded with the same two pieces, the Radetzky March (which I can enjoy by temporarily forgetting the evil fuckery that it was written to commemorate) and the Blue Danube.

(When I finally got to Vienna in 2010, I was very happy to visit the Musikverein for a concert, albeit not the New year’s concert.)

LikeLike

There’s some interesting material in Peikoff’s plays book. It’s not all as bad as the Shakespeare chapter. But how do you write an analysis of Othello and never mention race? I prefer my own analysis of Othello:

Click to access RTL-Godwin-other-minds.pdf

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here’s that Turner painting of an Incredible Hulk:

LikeLiked by 1 person

I see that one of us has more pull with WordPress than the other. I can’t get images to work in the comments.

LikeLike

Sometimes they work for me and sometimes they don’t. I think this proves that a fundamental flaw in the Law of Identity.

LikeLike

Ahem. The Dialectical One Has Arrived. 🙂

Forget those college transcripts… how about focusing instead on those rough sex scenes in her novels? I think she probably meant “hunks” after all. She would have DEFINITELY bemoaned naturalism’s “drained, embittered hunks whimpering occasionally about the hopelessness of life…”

Rand definitely liked non-whimpering hunks—a clear characteristic inherent in her projection of the ideal man… 🙂

Now on a more serious note: I have to admit that in “The Romantic Manifesto”, I do have a certain fondness for the material that focuses on the role and purpose of art in human life. I DO wish her cult followers did a bit more work in separating some of her thoughts on the nature and purpose of art from her own personal aesthetic (or even sexual) tastes. Going all the way back to the days of NBI, folks treated her pronouncements on film, music, sculpture, painting, literature, etc. as inseparable from the fabric of Objectivism. It led to such a stultifying environment such that if you even HINTED at liking something she despised, your sense of life, psycho-epistemology, and moral conscience were brought into question.

Just my two dialectical cents. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

As I said in the same aforementioned video: as a general rule, her reasons for liking the works she likes are more compelling than her reasons for disliking the works she dislikes. I’ve usually been grateful for her artistic recommendations (not always — the dreadful Donald Hamilton, egad), but her artistic dis-recommendations are far less reliable.

LikeLike

Just woke up from a dream in which I was disrecommending the work of Eric Clapton to my next door neighbor, Eric Clapton—who was mowing his lawn with a silent lawnmower. More when I’m really awake, and slightly more cogent.

LikeLike

Roderick: which video are you referring to?

LikeLike

This video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B5Z2jdUz95U

I haven’t posted it here at POT yet because I’m waiting to pair it with a related video that’s going up on Saturday.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks!

LikeLike

Paradoxically, I can’t fall back asleep because I’ve got “Cocaine” in my head. The song, I mean.

LikeLike

That song always reminds me of a particular night in the summer of 1980.

That is all. You may go about your business.

LikeLike

I don’t have any associations with “Cocaine,” but I do with “Layla”: mid-winter in Chicago. I was visiting with a dear friend who lived there. “Layla” came on the radio. I snorted and said that the song sounded to me like a cat being slaughtered without anesthesia. My friend paused, then said, very quietly, “Layla is my all-time favorite song.”

As I was saying, mid-winter in Chicago. We’re still friends, amazingly.

LikeLike

I heard the “unplugged” version of “Layla” before I ever heard the original, so that’s the paradigmatic version for me:

LikeLiked by 1 person

Much better than the original.

LikeLike

I offer another possibility. Maybe Ayn Rand meant to write “huck” instead of “hulk.” After all, Huck Finn was “idle, and lawless, and vulgar, and bad.” Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Huckleberry_Finn. He was absolutely not an aspiring industrialist, engineer, or architect. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

That might work, if I could bring myself to believe that Ayn Rand had ever read Huckleberry Finn.

LikeLike

In my callow youth I once overheard one classmate describing to another a comic-book character that I later realised was clearly the Thing from the Fantastic Four (“made of rock” was the description); but I also later realised that he’d confused him with the Hulk. But he also pronounced it “Holc.” Which is what later inspired me to create a character made of rock, named Holc, in one of my own comic books. “Good artists copy, great artists steal.”

LikeLike

“Today’s Tom Sawyer, he gets high on you;

the space he invades, he gets by on you.” — Rush

Relatedly, Nietzsche was a fan of Tom Sawyer and recommended the book to his friends. (I don’t know about Huckleberry Finn.)

Also relatedly, I enjoyed this movie, though I doubt Rand would have:

That last bit is closer to the books than one might think:

“We went down the hill and found Jo Harper and Ben Rogers …. Tom says: ‘Now, we’ll start this band of robbers and call it Tom Sawyer’s Gang. Everybody that wants to join has got to take an oath, and write his name in blood.’ … So Tom got out a sheet of paper that he had wrote the oath on, and read it. It swore every boy to stick to the band, and never tell any of the secrets; and if anybody done anything to any boy in the band, whichever boy was ordered to kill that person and his family must do it, and he mustn’t eat and he mustn’t sleep till he had killed them and hacked a cross in their breasts, which was the sign of the band. … And if anybody that belonged to the band told the secrets, he must have his throat cut, and then have his carcass burnt up and the ashes scattered all around, and his name blotted off of the list with blood and never mentioned again by the gang, but have a curse put on it and be forgot forever. Everybody said it was a real beautiful oath, and asked Tom if he got it out of his own head. He said, some of it, but the rest was out of pirate-books and robber-books, and every gang that was high-toned had it. Some thought it would be good to kill the *families* of boys that told the secrets. Tom said it was a good idea, so he took a pencil and wrote it in.”

LikeLike

First step: become Leonard Peikoff. Then…

LikeLike

“As a child, I saw a glimpse of the pre-World War I world, the last afterglow of the most radiant cultural atmosphere in human history (achieved not by Russian, but by Western culture). So powerful a fire does not die at once: even under the Soviet regime, in my college years, such works as Hugo’s Ruy Blas and Schiller’s Don Carlos were included in theatrical repertories, not as historical revivals, but as part of the contemporary esthetic scene. . . .

“[That period’s] art projected an overwhelming sense of intellectual freedom, of depth, i.e., concern with fundamental problems, of demanding standards, of inexhaustible originality, of unlimited possibilities and, above all, a profound respect for man. The existential atmosphere (which was then being destroyed by Europe’s philosophical trends and political systems) still held a benevolence that would be incredible to men of today, i.e., a smiling, confident good will of man to man, and of man to life.” (Romantic Manifesto 1971)

The two theatrical works Rand mentioned were, as evidenced below, not works trotting along without reins of the new communist regime. Pavel Vasilevich Samoylov was a distinguished actor who played the role of Ruy Blas, and in 1923 he was Honored Artist of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. http://www.encspb.ru/object/2804031328?lc=en

https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2004/11/schi-n12.html

Robert Stevens (2004)

“In his study, Russian and Soviet Theatre—Tradition and the Avant-Garde, Konstantin Rudnitsky recounts that Schiller’s plays held a special place in the theatre of the new revolutionary society of the Soviet Union.

“‘In the Civil War years, the plays of Friedrich Schiller enjoyed huge popularity. Their freedom-loving spirit, their characteristic opposition of heroism and villainy, their wealth of dramatically effective situations—all this guaranteed success with an unsophisticated audience. Intrigue and Love and The Robbers were enthusiastically acted by amateurs in numerous clubs. The Bolshoi Dramatic Theatre in Leningrad, led by Alaxander Blok, Maria Andreevna and Maxim Gorky, opened on February 5, 1919 with a production of Schiller’s Don Carlos’ (Russian and Soviet Theatre—Tradition and the Avant-Garde, page 75,).

“Rudnitsky continues, ‘The attraction of the broad masses to the classical repertoire was explained not only by the fact that the beauty and emotional richness of plays by Griboedov, Gogol and Ostrovsky, Shakespeare and Molier, Schiller and Beaumarchais and other great writers were revealed for the first time to audiences who had previously not had the opportunity of going to the theatre … they served as it were to unite the distant past with the present day and instilled in the audience feelings and ideas close to and consonant with the Revolutionary struggle’ (ibid. 48).

“The Bolshevik revolutionary and literary figure Anatoli Lunacharsky noted of the play that ‘in this, according to Schiller’s idea, first apostle of the idea of freedom, we the people of the revolutionary avant-garde, can in a sense recognise our predecessor … not for one moment does the audience doubt in the final triumph of Posa’s idea, a triumph which Posa himself, of course, could never have foreseen’ (ibid. page 49)”.

LikeLiked by 1 person