Stoicism, particularly in its ethical and political aspects (a defense of individual self-mastery on the one hand and commercial society on the other – for the latter, see, e.g., Cicero’s De Officiis), has been enormously influential throughout western history. During the Roman period it took on something like the character of a mass religious movement; Stoics were also statistically overrepresented among assassins or attempted assassins of Roman emperors. (One third of all Roman emperors died by assassination, so that’s not an insignificant number.) Later on, philosophical thinkers as diverse as Augustine, Descartes, Spinoza, Locke, Adam Smith, and Kant would draw on Stoic ideas (though always selectively) in crafting their own ethical and political views.

Cato regrets that he will not be at home to entertain Julius Caesar.

It was also common for anti-imperialist, anti-monarchical writers in the 18th century, including many of the American founders (such as New York governor, Anti-federalist campaigner, and later u.s. vice-president George Clinton – not the musician, alas), as well as British radical republicans like Trenchard and Gordon (authors of Cato’s Letters), to sign their anonymous pamphlets with the name of Cato (the Younger), the Stoic who resisted Julius Caesar’s rise to power. George Washington had Joseph Addison’s play about Cato performed at Valley Forge to inspire the troops. (The Cato Institute also takes its name from this tradition.)

Stoicism is undergoing a bit of a renaissance today, both in academic philosophy (partly because it’s seen as a way of mediating between the eudaimonistic, virtue-ethical Aristotelean approach and the deontological Kantian approach; partly because of Foucault’s role, in his later works, of reviving the “care of the self” tradition in ethics) and in works of popular psychology. (There’s also a striking similarity between the Stoic theory of the emotions and that of Sartre, though I’m not aware that anyone besides myself has commented on this.)

The Stoa today, perhaps after a Randian bombing campaign.

Primarily in response to the popular-psychology use of Stoicism, Randian scholar Aaron Smith has an article up today warning against the perilous influence of the Stoa and urging the preferability of the Randian alternative. (CHT Sheldon Richman.)

I find Smith’s piece a bit frustrating. I mean, I’m broadly sympathetic with his criticisms of Stoicism, but Smith makes it sound, e.g., as though the Stoics had nothing to say about how to reconcile free will with determinism, whereas they had a fairly well-worked out and sophisticated theory.

Identifying the details of the theory is admittedly a bit tricky, as there’s no one canonical Stoic text or even author. The problem is that the theoretical foundations of Stoicism were in Greek mansucipts – by e.g. Zeno of Citium, Cleanthes, Poseidonius, Panætius, etc., and above all by the brilliant and prolific Chrysippus (who to all evidence appears to have been a mind in the same league as Plato and Aristotle) – that are mostly lost. We have to reconstruct their views from quotations, reports, etc. in other authors. (Some famous classical scholar – I forget who – once said he would rather recover a single lost page of Heracleitus than all of the purported 700 or so lost works of Chrysippus. For my part, I confess I would rather recover a single page of Chrysippus than all of Heracleitus.) The Stoic texts that survive intact are not foundational texts; they’re popularising works (mostly, though not exclusively, Roman) that focus more on self-help than on philosophical foundations; of this nature (a bit like the pop-psychology Stoicism books today, actually, though rather better written) are the works of Seneca, Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius, etc. (and Cicero, when he has his Stoic hat on), though they do occasionally refer helpfully if not extensively to some of the background theoretical material. So reconstructing Stoic doctrine is a bit of a jigsaw puzzle task. Happily, we have a lot of pieces so the task is not intractable.

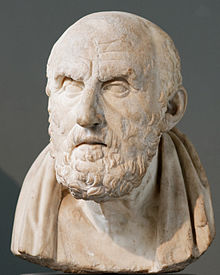

Chrysippus, on being told that all 700 of his works have gone missing.

In any case, the basic idea is that something is up to you if it can be caused by your act of rational judgment, without any further causal factors needed once your act of rational judgment occurs. The fact that your act of rational judgment itself has deterministic causal antecedents is irrelevant, on their view. For something to be up to you is for its happening or not happening to depend on what rational judgment you form. (In other words, a) the causal chain has to go through your act of rational judgment rather than bypassing it [that’s a standard compatibilist or soft determinist move], and b) [and here comes the distinctive interiorising Stoic move that most compatibilists would not sign on to] the causal chain has to go solely through that act of rational judgment, rather than the outcome’s depending on interaction between internal and external causal chains.

I don’t think this view (either the (a) part or the (b) part) ultimately works (for some of my problems with views like (a), see this paper), but it’s not something that can be refuted simply by pointing to a few Stoic quotations and saying “look! they say they believe in free will, but they also say they believe in determinism! Contradiction! Guilty!”

It would also have been interesting for Smith to have explored the similarities (sometimes quite strong) and differences (also strong, of course) between Stoic and Randian views about the emotions, the relation between ethics and human nature, etc.

Howard Roark, contemplating what he cannot control.

For example, when Howard Roark, the protagonist of Rand’s novel The Fountainhead, says:

“I’m not capable of suffering completely. I never have. It goes only down to a certain point and then it stops. As long as there is that untouched point, it’s not really pain.”

– he sounds pretty damn Stoic. (Though so does Dominique, whose quest is nevertheless for an invulnerability subtly but crucially unlike Roark’s, in ways that would be worth teasing out in this context.)

Likewise, when the Roman Stoic Seneca says:

“A living being has an attachment to itself, for there must be a standard by which all other things are judged. … Since I treat my own welfare as the standard for all my actions, I am concerned for myself above everything else. … Every living thing has an initial attachment to its own constitution; but a human being’s constitution is a rational one, and so a human being’s attachment is to himself not qua living being but qua rational being. For he is dear to himself in respect of what makes him human.”

– he sounds pretty damn Randian. Though again there are important differences too.

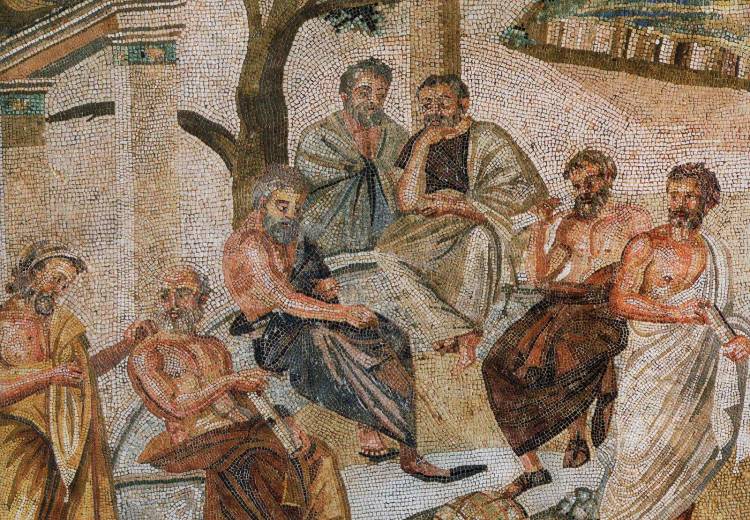

Make philosophy, not war: A mosaic of Plato’s Academy, from Pompeii.

Really the article exemplifies a recurring problem with Rand’s own approach to philosophy, which too many of her followers have likewise embraced: an emphasis first and foremost on philosophy as war, as a matter of crushing the wrong views, which tends to lead, if not exactly to a “shoot first and ask questions later” approach, then at least an approach of “ask a few questions, and if the answers don’t sound quite right, start shooting without investigating too closely, trying to sort friend from foe, or trying to convert foe to friend.” Philosophy as a battleground, not as a field of potentially fruitful exchange. Thus it’s not philosophia, love of wisdom, so much as philonikia, love of victory. And so this piece passes up any opportunity of the form “let’s try to use Stoic ideas as useful occasions to think and learn about these issues” in favour of jealously guarding the faithful against lapses into heresy. (Of course the same criticisms apply to mainstream academic philosophers’ engagement with Rand.)

In philosophy I generally find a military or policing approach less valuable than a catallactic approach, in Hayek’s sense of the word:

“These terms [e.g., catallactics, catallaxy] are particularly attractive because the classical Greek word from which they stem, katalattein or katalassein, meant not only ‘to exchange’ but also ‘to receive into the community’ and ‘to turn from enemy into friend’, further evidence of the profound insight of the ancient Greeks in such matters ….”

Admittedly, this is an insight that the ancient Greek philosophical schools often lost sight of when they were engaging with one another. But we should strive to imitate their best moments, not their worst ones.

Pingback: Randians vs. Stoics | Austro-Athenian Empire

Guarding the faithful against lapses into heresy would make slightly more sense (without quite making sense) if Objectivism were more determinate a “system” of thought than it in fact is. As it stands, the tactic of “guarding the faithful against heresy” seems more to serve the purpose (whether wittingly or not) of concealing the fact that there is no orthodoxy there to protect. How much, exactly, did Rand have to say of a worked-out nature about happiness? That it was a form of non-contradictory joy? That it proceeds from the achievement of rational values? That it’s not to be understood in hedonistic terms? Those are slogans, not philosophy. At the end of the day, there isn’t enough there even to fill a short primer on the subject (of the length and complexity of, say, Christine Vitrano’s The Nature and Value of Happiness, the book I use to teach the subject in undergrad classes)..

Smith’s attack on Stoicism gives the impression that he’s criticizing Stoicism on the basis of some worked out non-Stoic doctrine that’s sitting there in Rand’s texts, but that’s an illusion. What doctrine? Rand’s works are at least as much of a jigsaw puzzle as the Stoics’, arguably less rewarding to put together, and less action-guiding once put together.

Had I not read Smith’s piece in response to your post, I doubt I would have gotten past his advice to “steer clear of Stoicism as a philosophy of life.” The assumption seems to be: either we accept Stoicism wholesale, or we throw it in the trash. The whole thing seems like a caricature of the view ascribed (apocryphally, I think) to the Caliph Omar on encountering the Library of Alexandria: “If these books agree with the Qur’an, they’re superfluous, and if they disagree, they’re useless–so burn them.” To his credit, I guess Smith would make sure to buy the library before he burned it. (Of course, if the Library of Alexandria had been in Gaza, and Caliph Peikoff or Journo had his hand on the trigger finger, it probably would have gone the way of Persepolis at the hands of Alexander.)

Put it this way: at a minimum, we need Stoicism in order to read Objectivist philosophical polemics; you need a certain invulnerability to boredom and tedium to make it through. I guess I was tougher when I was younger. The older I get, alas, the less able I am to pull it off.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The “Library of Alexandria” seems to have existed in several iterations (and locations within the city) over the centuries, and there are reports of various groups (from Julius Caesar’s troops, as collateral damage, to Christians and later on Muslims, deliberately) having a hand in destroying one or another of them. But the precise dates and perpetrators are all uncertain, the reports tending to be much later than the events reported, and authored by hostile sources. A time traveler anxious to rescue the library’s lost contents would have to make repeated trips first of reconnaissance and then of salvage. (And then would probably turn out to be the inadvertent cause of each destruction.)

But those 700 books of Chrysippus would have been lost somewhere along the way in there. (Admittedly, that “700” figure probably describes 700 scrolls, which correspond to individual books within a larger book (like the ten books of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics) rather than to entire works. Aristotle’s works vary anything from one book to fourteen; so if Chrysippus’s did likewise, he might have had anything between 700 standalone works and a mere 50.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another Stoic parallel, from the other Smith: in her book Viable Values, Tara Smith defends the thesis that ill-gotten goods lack value. “Something is in a person’s interest only if it offers a net benefit to the person’s life” (p. 168). So if I steal food, however nutritious, the fact of having stolen it (assuming fixed property rights) nullifies whatever value it brought me qua nutritious. Whereas if I honestly buy the same exact food, the fact of having honestly bought it promotes my flourishing.

Of course, this thesis somehow has to be squared with the Objectivist principle (also endorsed by Tara Smith) that moral principles involve exception-clauses for emergencies. So my stealing a loaf of bread is one thing (and a value-nullifying thing), but Jean Valjean’s doing so in the context of Les Miserables is another.

You might think that there’s something to be learned by reading the Stoics on this subject, but then, you might just decide to steer clear of them. Up to you, so to speak.

LikeLike

“You might think that there’s something to be learned by reading the Stoics on this subject”

Or even the dreaded Plato:

https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle/2142/12087/illinoisclassica1011021985IRWIN.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

LikeLiked by 1 person

On Stoics as tyrannicides, see an interesting article by David Sedley, “The Ethics of Brutus and Cassius.” (https://www.academia.edu/30317147/The_ethics_of_Brutus_and_Cassius)

Sedley argues that Brutus was basically a Platonist and that Cassius was basically an Epicurean. The latter seems particularly odd support for tyrannicide, but nevertheless Sedley argues that Stoicism was particularly lacking in enthusiasm/support for tyrannicide. He claims that not one of Caesar’s assassins was a Stoic. As I recall (it’s been a while since I read the article), his argument is that the Stoics were more concerned about the “slavery” of the non-Sage to his passions and unwise views than about the more material kind. The Sage is always ultimately free, even under tyranny, and also has the ready option of suicide rather than suffer indignity. Thus, for Stoicism, the material/political/social conditions of life don’t have the same importance they have under many other philosophies.

LikeLike

Interesting; thanks! But I think Sedley describes the Antiochean version of Platonism (to which Brutus is thought to have adhered) somewhat misleadingly. He says, rightly, that for Antiochus virtue is sufficient for mere happiness but not for the highest happiness, and so that there are goods other than virtue, a view Brutus seems to hold but that the Stoics reject.

So far so true, But a) Antiochus also argued (Sedley touches on this in passing but doesn’t really emphasise it) that the Stoic doctrine was only verbally different from his own, since the Stoic class of “preferred indifferents” corresponded to the goods beyond virtue in his own theory (and Plato’s and Aristotle’s theories, as he interpreted them); and b) even if we think Antiochus is wrong about this, it’s at least true that when Stoics were writing loosely in their popularising works they would often refer to things as “goods” that according to their strict official theory are actually preferred indifferents rather than goods. So I don’t think Brutus’s use of the term settles things one way or another.

I can’t remember where I read that statistic about Stoics being overrepresented in assassination attempts. I presume Lucan was one of the data points but don’t know about the others.

LikeLike

P.S. – It’s true that the Stoic has less reason to mind tyranny. But by the same token the Stoic has less reason to fear the consequences to himself of attempting an assassination. So I’m not sure that cuts more one way than the other. The Stoics did hold that only just rulers count as genuine rulers, a view that historically has often been associated with defense of tyrannicide.

There’s also the idea of the “Stoic Opposition” —

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stoic_Opposition

— though a) it’s not clear how much of a genuine thing that was, and b) opposition is of course not the same thing as assassination.

LikeLike

I can’t say anything further about Brutus—though it would be an interesting thing to look into. With regard to Antiochus specifically, I’m reminded of Myles Burnyeat’s remark that Antiochus’s attitude about Stoicism and Platonism being only verbally different says much about the dreadful state that philosophy had fallen into at that time! (I wish I could remember where he said that, but I can’t.)

I does seem to me that the general thrust of Stoicism should favor cultivating personal integrity over world-changing. And in that sense, Sedley would be right. As Epictetus says, there are the things that belong to you and the things that don’t, and your responsibility is only for the former. But of course, philosophers are adept in the art of having it both ways. If an Epicurean can talk himself into the view that his philosophy requires tyrannicide, anything is possible.

LikeLike

Well, for many of the Stoics the class of preferred indifferents has much of the same content as the class of goods recognised by other philosophers, and so they’re committed to pursuing those things even if they don’t care whether they get them.

LikeLike

And judging by Cicero’s reports in De Officiis, some of the Stoic philosophers were willing to endorse some pretty sharp and shady business practices in order to gain the preferred indifferent of material wealth. The movement may have started with a bunch of homeless guys living in barrels but it didn’t stay there.

LikeLike

Yes, so of course there’s the means available to support world-changing, including political activism, assassination, and so forth. But I don’t see much evidence that they advocated any such things. And for the reasons I’ve given, I wouldn’t be expecting them to. The basic spirit of their philosophical undertaking seems to me to be against it.

I think there’s a basic psychological difficulty in Stoicism that is well captured by your phrase, “committed to pursuing [certain] things even if they don’t care about them.” A rational commitment to doing something you don’t care about may be possible, but it doesn’t seem human or sustainable long term or happiness-producing. If that’s right, it’s bad for Stoicism, since—it seems to me—one of the two main attractions of Stoicism (to those who find it attractive) is the promise of an escape from the tyranny of the passions. (The other main attraction being to put the moral status of your life completely under your control.)

LikeLike

On political activism — well, they certainly engaged in a fair bit of it, from Cato to Marcus Aurelius. And Cicero’s De Officiis, which is heavily dependent on the ideas of such Stoics as Panaetius and Poseidonius (“officiis” translates the Stoic “kathekonta,” appropriate actions), assigns political activism a central place among the kathekonta.

Moreover: justice, he says there, involves not only the duty to refrain from wrong oneself, but the duty to “shield from wrong those upon whom it is being inflicted”; those who decline to do so, on the grounds that they are “occupied solely with their own affairs,” are “traitors to social life.” And he accordingly describes tyrannicide as “of all glorious deeds … the most noble.” “There can be no fellowship between us and tyrants … just as some limbs are amputated if they are … harming other parts of the body, similarly if the wildness and monstrousness of a beast appears in human form, it must be removed from the common humanity … of the body.”

Admittedly it’s hard to know, with regard to De Officiis, where Cicero’s Stoic sources stop and Cicero the philosophical chameleon begins. But Cicero does say in De Officiis that “Panaetius, then, has given us what is unquestionably the most thorough discussion of moral duties that we have, and I have followed him in the main, but with slight modifications,” and refers again to “Panaetius himself … whom I am following, [though] not slavishly translating, in these books”; and indeed he cites Panaetius’s lost Peri to kathekontos repeatedly throughout. If De Officiis is as heavily dependent on Panaetius as this implies (and many commentators seem to think so), then political activism, not excluding the possible need for tyrannicide, seems to have been part of at least some Stoic theories.

I say a bit about Stoicism’s increasing orientation over time toward worldly concerns here:

Click to access chap5.pdf

On the stability of Stoic motivation — ultimately I agree with you, but I try to motivate the Stoic view in this handout:

Click to access stoic-handouts.pdf

LikeLike

Thanks for the references; I enjoyed them both. I especially liked the handouts—very well done.

I must confess I hadn’t realized that Cicero translates kathêkon by officium. I wonder about its appropriateness, but I suppose I’m in no good position to judge. And I’ll have to think more about it.

Cicero’s references to tyrannicide were all specifically to the assassination of Julius Caesar, an event that can have predated his writing of De Officiis by no more than a few months and in which Cicero was very personally interested. I doubt Panaetius much determined his attitude!

On a more philosophical note, it’s interesting that the Stoics pioneered the idea of natural law but do not seem to have developed very strong ideas about the justice of competing political constitutions, nor, crucially, a strong conception of political freedom. The matter of comparing constitutions seems particularly odd, inasmuch as there was ample precedent for it. If they had had stronger ideas on these two points, presumably they would have had stauncher ideas about resistance to tyranny. That seems to be Sedley’s claim, which I still find persuasive. Sedley says, by the way, that Seneca actually criticized Brutus’s assassination of Caesar as unStoic! (The argument being that Caesar’s monarchy was halfway to the best constitution, a just monarchy.)

LikeLike

“Cicero’s references to tyrannicide were all specifically to the assassination of Julius Caesar”

He mentions Phalaris also as a tyrant whose killing was justifiable. (Off. III.6.) And he praises Aratus while describing his overthrow of the tyrant Nicocles (II.81), though what he praises him for specifically is how he handled the issue of property restitution afterward.

“Sedley says, by the way, that Seneca actually criticized Brutus’s assassination of Caesar as unStoic! (The argument being that Caesar’s monarchy was halfway to the best constitution, a just monarchy.)”

What Seneca says is a bit more nuanced than that. He doesn’t say that Caesar’s rule was halfway to a good anything. What he says is that if a) Brutus killed Caesar merely out of opposition to kings in general, this was a mistake, since there can be good kings, and a good kingship is actually the best constitution; and if b) Brutus instead killed Caesar out of opposition to unjust kings specifically, this was still a mistake, because Brutus should have known it was inevitable, under the circumstances then prevailing [note: he does not say under any and all circumstances], that whoever succeeded Caesar would be just as bad, so killing Caesar was pointless. He then adds that c) Brutus was nevertheless not guilty of ingratitude to Caesar for killing him when Caesar had previously spared his life, since Caesar’s failing to fully exercise his unjust powers is not a appropriate subject for gratitude. (And he takes care to note that he regards Brutus as a good man.)

Here’s the passage, from “On Benefits,” II.20:

“The question has been raised, whether Marcus Brutus ought to have received his life from the hands of Julius Caesar, who, he had decided, ought to be put to death. As to the grounds upon which he put him to death, I shall discuss them elsewhere; for to my mind, though he was in other respects a great man, in this he seems to have been entirely wrong, and not to have followed the maxims of the Stoic philosophy. He must either have feared the name of ‘King,’ although a state thrives best under a good king, or he must have hoped that liberty could exist in a state where some had so much to gain by reigning, and others had so much to gain by becoming slaves. Or, again, he must have supposed that it would be possible to restore the ancient constitution after all the ancient manners had been lost, and that citizens could continue to possess equal rights, or laws remain inviolate, in a state in which he had seen so many thousands of men fighting to decide, not whether they should be slaves or free, but which master they should serve. How forgetful he seems to have been, both of human nature and of the history of his own country, in supposing that when one despot was destroyed another of the same temper would not take his place, though, after so many kings had perished by lightning and the sword, a Tarquin was found to reign! Yet Brutus did right in receiving his life from Caesar, though he was not bound thereby to regard Caesar as his father, since it was by a wrong that Caesar had come to be in a position to bestow this benefit. A man does not save your life who does not kill you; nor does he confer a benefit, but merely gives you your discharge. ”

Seneca’s promise to discuss the case of Brutus more thoroughly elsewhere is not fulfilled, at least in any works we possess (unless we count the passing line in De Ira where, with no mention of Brutus specifically, he says that Caesar’s assassins were motivated by insatiable ambition, which seems inconsistent with what he says about Brutus here.)

Of course this is an area where he had to tread carefully. But elsewhere in “On Benefits” (VII.15) he gives the Athenian veneration of Harmodius and Aristogeiton for their attempted assassination of Hippias as an example of how gratitude is justified for attempted benefits even when the the benefactor is unsuccessful; on its face this looks like he regards the assassination attempt as justified.

The line in Seneca’s “Hercules Furens” about there being no more acceptable sacrifice to Jupiter than the blood of a wicked king has also been cited as evidence (most famously by Milton) for Seneca’s support for tyrannicide. But given that Hercules goes insane immediately after saying this, and starts scheming to overthrow Jupiter too, the interpretation is hardly straightforward.

“If they had had stronger ideas on these two points, presumably they would have had stauncher ideas about resistance to tyranny.”

Possibly. But on the other hand, I continue to think that the Stoic view that an unjust king is no king at all (which they borrowed from the explicitly pro-tyrannicide Xenophon) is an especially strong basis for resistance to tyranny (as it certainly became later).

To quote a rather different tradition:

“The king Xuan of Qi asked, saying, ‘Was it so, that Tang banished Jie, and that king Wu smote Zhou?’

Mengzi replied, ‘It is so in the records.’

The king said, ‘May a minister then put his sovereign to death?’

Mengzi said, ‘He who outrages the benevolence proper to his nature, is called a robber; he who outrages righteousness, is called a ruffian. The robber and ruffian we call a mere fellow. I have heard of the cutting off of the fellow Zhou, but I have not heard of the putting a sovereign to death, in his case.'”

LikeLike

Thanks for all these details, especially the expansion on Seneca. Very interesting stuff! (I can’t seem to reply directly to your most recent reply, so I’m replying here.)

LikeLike

Any thoughts pro or con about the idea of the “Stoic opposition”?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stoic_Opposition

LikeLike

On the Stoic Opposition, really, I hadn’t given it much thought. But on your prompting, I read the Wikipedia article through, and two things occur to me. First, all the evidence cited seems to concern their persecution by the emperors, not their own activities. Therefore, it may be more indicative of imperial paranoia than of concerted or dangerous opposition on the part of these Stoics. Second, perhaps other than rashly signalling their disapproval of the emperors, they don’t seem to have taken much action. There were of course plots against Nero, for example, and no doubt the others, but there doesn’t seem to be much evidence of Stoics being involved in them. Certainly, they weren’t the ringleaders in the cases I know about.

Sedley sort of ridicules the Stoic Opposition figures as being more interested in staging virtue-signaling suicides in emulation of their heroes Socrates and Cato than in actually resisting tyranny or assassinating tyrants. The account of Thrasea’s death that Sedley points to in Tacitus is consistent with that, but I shouldn’t think it’s very trustworthy (as no ancient historian is when it comes to details, speeches, etc.). On the plus side, it does seem that certain prominent Stoics in the first century were unhappy with imperial tyranny for principled reasons and were willing to let that be known, which was a risky thing to do. There’s something to be said for that.

LikeLike

I like this post a lot. I of course know much less about Randians than you do, but the bit about philosophy as war rings true, and, as you say, is by no means restricted to Randians. Your practice of a more ‘catallactic’ approach has long been a source of inspiration for me, even if I have too often succumbed to the warrior ethos myself.

I don’t recall the details, but I do at least seem to recall Nussbaum’s Upheavals of Thought mentioning similarities between the Stoic theory of emotions and Sartre’s theory, in connection with Robert Solomon’s Sartre-inspired The Passions.

Your remarks on the Stoics in the comments here strike me as largely right, but two additional points might be worth making and consistent with what you say.

First, whether Antiochus was right to think that his own view differed from the Stoics’ only verbally, he seems wrong to think that Aristotle’s does, even on a fairly Stoic-friendly interpretation according to which no bodily or external good is part of happiness. The difference, as Dan Russell clearly brings out in his Happiness for Humans, is a difference in how Aristotle and the Stoics conceive of rational activity. For the Stoics, rational activity is simply a matter of thinking and choosing, and so is highly independent of external and bodily goods. For Aristotle, rational activity is activity that is expressive of or guided by thinking and choosing, but is (at least sometimes) partially constituted by bringing about changes in the world beyond my own thoughts and choices. Hence rational activity often depends on external and bodily goods for its success, and so virtue cannot be sufficient for happiness, even for some less-than-full version of it. Admittedly, what Aristotle says about this is less than transparently clear, and Antiochus could have interpreted him in a more Stoicizing way with some plausibility. But I think the Stoicizing interpretation is mistaken and less philosophically plausible in any case. The Stoic restriction of rational activity to thinking and choosing is what allows them to distinguish between telos and skopos in the way they do — the goal of an action being internal to rational activity narrowly conceived, so that achieving the goal is a necessary condition for the success of the activity, with the aim being external to the activity, so that achieving the aim is not a necessary condition for the success of the activity — which finds no clear parallel in Aristotle.

Second, I think it might be misleading to describe the Stoics as committed to aiming at something even if they don’t care about it. Not caring suggests indifference in the standard contemporary sense of the word, but Stoic ‘indifference’ — not making a difference to happiness — does not obviously imply that. It seems to require some sort of attitudinal difference to goals and to aims, but actually aiming at something seems inconsistent with not caring about it. The difference might be more aptly captured in contemporary terms of ‘attachment’ — I can clearly aim at something and put a lot of effort into achieving it without being attached to achieving it — but even that seems potentially misleading, if only because ‘attachment’ is vague. The core idea is just that I don’t see achieving the aim as essential to my life being a good one rather than a bad one. That’s clearly an attitudinal difference from seeing it as essential, but it’s not at all obviously inconsistent with caring about achieving the aim, nor does it seem bound to generate any instability in motivation, and it’s at least not so implausible to think that we should not see anything other than our own virtuous thinking and choosing as essential. It has at least some intuitive plausibility independent of any obsession with independence or invulnerability; one might think that it’s implicit in judgments to the effect that people who respond virtuously to serious misfortune and do not achieve their aims but pursue them wisely and courageously live admirable and hence good lives. Ultimately I think Aristotle accommodates those intuitive judgments more plausibly than the Stoics, but the Stoic view isn’t nearly so implausible as some of its critics would have it. (Katja Vogt gives a nice, concise defense of the distinction between goodness and selective value / preferred indifferents along these lines in her chapter in the recent Cambridge Companion to Ancient Ethics, a pre-publication version of which is available here: https://katjavogt.com/wp-content/uploads/intro-vogt-virtue-and-happiness-in-stoic-ethics.pdf).

I’m not sure I’m with you on Chrysippus vs. Heraclitus, but my go-to in the traditional classicist game of picking x number of pages of some lost text in exchange for x number of pages of some extant text has typically been any x of Chrysippus for any x of Latin love elegy. In part that’s just to scandalize Latin poetry people, though.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ditto. I’ve often found, introspectively, that I’ve been attracted to philonikia as an ideal when I thought for whatever reason that philosophia was a luxury I couldn’t “afford.” Rand often gives that impression herself; I had a predisposition to that view (probably still do), and cottoned on to it early on in my “Objectivist career.”

Rand scholarship has improved in quality (especially on the ARI side) to the extent that Objectivist scholars have left the warrior ethos behind, at least in their “official” scholarship. But the standard move has been to compartmentalize, engaging in properly philosophical discourse in professional settings, while making sure to have another forum within which to unleash the warrior ethos. BHL often seems to function along similar lines: for lots of people there, blogging is an exercise in unbridled belligerence, to be left behind in professional settings where one comports oneself in a more respectable way (while expressing attitudes more appropriate to philosophy: not quite the same as comporting oneself in a more respectable way, but related to it).

Rand explicitly comes out and compares philosophy to warfare in “Philosophy: Who Needs It,” her 1974 speech at West Point, also her most sustained piece of “meta-philosophy,” if you want to call it that. But the “warfare” view is scattered throughout her works, and implicit in the way she writes. It also explains her love of two fallacies in particular: ad hominem abusive and strawman. She can’t seem to go a page without committing at least one.

Rand’s view of philosophy as warfare seems connected somehow to her view of warfare itself–a view so extreme she can’t seem to fit it within the compass of her official philosophical commitments. Try to explain Rand’s views on warfare by way of the trader principle and non-initiation of force principle.

My favorite is her view on amnesty for draft evasion in Vietnam. She was against the draft, which she likened to slavery, but objected to amnesty for those who evaded the draft if (but only if) their draft evasion was specific to the war in Vietnam. It’s one thing (she claimed) to be against the draft on grounds of general principle (even if the principle ends up being divine command theory); it’s another thing (and a wholly unprincipled thing) to be against the war in Vietnam. To oppose the war in Vietnam (she claims) was to express sympathy for the North Vietnamese or Vietcong, which was to sanction the murder of U.S. servicemen, which was unforgivable–which entailed that you should rot in prison for evading the draft. It sounds crazy, but go and read it for yourself (Letters of Ayn Rand, pp. 657-58, May 30, 1973). Philosophy is warfare, warfare is philosophy, and human lives are the collateral damage of their encounter.

LikeLike

Despite my eirenic propensities, I confess I do have a fondness for Rand’s line: “A political battle is merely a skirmish fought with muskets; a philosophical battle is a nuclear war.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I see the attraction, but her statement has the unfortunate implication that we should be reluctant to engage in fundamental philosophical controversy for fear of mutual assured destruction.

One of her more paradoxical claims on this topic, an odd hybrid of the Gospels, the Beatles, and the Harry Potter movies avant la lettre:

It somehow works as rhetoric even if it makes no sense taken literally. Three obvious questions among others: Why would the shriveled creature not be able to eat the cookies he stole? How well does the image of the shriveled creature cohere with Rand’s conception of evil as evasion, or even of envy as hatred of the good for being the good? And how plausible is it to imagine that the creature’s would-be Objectivist adversary might sustain an attachment to philosophy by conceiving the activity as an attack on a shriveled cookie thief/terrorist while motivated by a conception of love tied (on the one hand) to a Hugo-esque ideal of human potential but expressed (on the other) in unconcealed rancor? Try getting through graduate school that way.

A professional philosopher really has only two options when it comes to Rand’s rhetoric: either you reject it as basically neurotic, in which case you make a point of not internalizing it; or you internalize it but compartmentalize what you’ve internalized so as to be able to function effectively as a professional. (Those aren’t literally exclusive or exhaustive options, but I think they cover most of the relevant territory.) Either way, I sometimes wonder whether it might have been better not to have encountered her work at all.

LikeLike

“All You Need Is Love” came out in 1967, and “Age of Envy” was either written or published in 1971, so I take it that Rand’s “For once, it is I who say…” is likely (at least in part) to be an allusion to the song.

LikeLike

There’s also Jackie DeShannon’s “What the World Needs Now is Love” from 1965.

LikeLike

Seems sad to think that Rand would deliberately have insisted on endorsing a conception of love that was the “opposite” of Jackie DeShannon’s. I almost prefer to think that she’d never heard the song. But you never know.

LikeLike

“Why would the shriveled creature not be able to eat the cookies he stole?”

With regard to the cookies, Rand seems to be ruining one metaphor by sinking it under another metaphor. She wants to say that the wizened child wants to “have his cake and eat it too” (“eat his cake and have it too” actually would make the meaning of that saying clearer), but Rand is determined to avoid any suggestion that the wizened child might have come by his cookies innocently, so she changes it to “steal his cookies and eat them too,” losing track of the fact that since stealing is a one-time act rather than an ongoing possession, it no longer conflicts with eating. This is a kind of sloppiness in writing that she wouldn’t have permitted herself in her novels.

That said, though, her wizened-child metaphor is an expression of a broader idea that evil is “not single and big [but] many and smutty and small” (The Fountainhead), or that evil is not a “tall warrior in a steel helmet” or “human dragon spitting fire” but a “big, fat, slow, blond louse” (We the Living). This is an idea that she shares with Tolkien and C.S. Lewis — less surprisingly than it might seem, given the common Thomistic [really Augustinian of course, but that’s a realisation Rand would have choked on] background, sort of, of all three. (In Lewis’s “Great Divorce,” the path from heaven to hell involves shrinking, as hell is just a microscopic dot on earth, as earth is just a microscopic dot within heaven.) In Rand’s case the Thomistic influence was supplemented by Nietzsche’s bad/evil distinction (what Nietzsche calls bad is Rand’s evil, her James Taggarts; what Nietzsche calls evil is Rand’s misguided good, her Gail Wynands) as well as by Victor Hugo, whose antagonists likewise sort into James Taggarts and Gail Wynands.

Speaking of Tolkien, one of the things that bugged me about Peter Jackson’s version of LOTR is Saruman’s glorious-tragic death falling from his tower. Tolkien instead had Saruman gradually diminish to a cheap con man who dies in a skirmish in a back alley in the Shire, which expresses Tolkien’s view of evil. (LOTR and Atlas are incidentally alike in turning traditional tropes on their head. LOTR is a quest concerning a magical object — but the aim of the quest is not to acquire it but to get rid of it. Atlas has as its climax the villains torturing the hero — but their goal is not to get him to submit to them but rather to get him to become their dictator. Both are stories about the refusal of power.)

I don’t think her problem was that she conceived evil as shriveled and puny. Her problem was that she was convinced that all or most philosophical error, from great minds at least, was the result of evil.

“I sometimes wonder whether it might have been better not to have encountered her work at all.”

Surely true for some. Definitely not for me.

LikeLike

How does one lose track of a fact like that? Call me a concrete bound mystic of muscle, but I’d have thought (based on my own experiences with cookies) that the point of stealing a cookie was to eat it, not to make an ideological point about it. But she did say that Americans were naive about evil.

I’ve always found this set of claims hard to reconcile with one of my earliest encounters with evil–namely, the kid down the street much larger than me who beat the shit out of me, then grabbed me by the ankles and dragged me through dog shit until I was covered with it, then laughed at me, left me there and walked home (fifty yards away). If anyone seemed small, soft, slow, and smelly (which at least approximates “smutty”), it was me, not him.

But even if we ascend from such moral trivia to the world historical stage, I don’t think anyone would describe the Wehrmacht or the Red Army–or any of the armies of capitalist imperialism–as a bunch of shriveled wimps. Arguably, all three sets of armies had their share of “tall warriors in steel helmets,” and “dragon spitting fire” is not a bad description of a tank, flame thrower, or strategic bombing campaign. Even if we focus at the micro-level on evil individuals, it seems a stretch to describe Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini, or Saddam Hussein as puny little men trying to compensate for their small physical (or even psychological) stature. How many people have faced death as calmly as Saddam Hussein? Even I was impressed by it.

The one person her account “accurately” describes is her version of Kant (the “arrogant bookkeeper with a rupture”), or I suppose, her versions of the other philosophers she most intensely despised (Plato, Augustine, Descartes, Hume, Schopenhauer, Rousseau, Marx, Mill, Dewey, Rawls, and Nathaniel Branden), but doesn’t that by itself suggest the explanatory limits of the thesis?

There is, I suppose, a brand of evil that answers to the description she gives, but there’s also such a thing as powerful people drunk on the very real power they have–people who relish using their strength on those weaker than them. Rand sometimes writes as though the latter phenomenon didn’t exist, or was somehow derivative on the former, but I don’t see why anyone would believe that.

LikeLike

The Augustinian-Randian claim isn’t that evil people are physically weak. It’s that evil is parasitic on good, that it has no power of its own. Sometimes that means that evil people depend for their success on acquiescence by good people (the “sanction of the victim”). Sometimes it means that they’re able to succeed only because of things good people have done (like Nazis turning scientific and industrial achievements to evil ends) Sometimes — as in the case of your bully example, and so less helpfully to you — it means an individual’s evil is parasitic on that individual’s own good traits (e.g., your bully couldn’t succeed in his evil without possessing the good trait of strength). Rand tends not to dwell on the latter case.

LikeLike

Right, but the second interpretation strikes me as trivializing the whole thesis. The individual’s evil may be parasitic on a good trait, but the individual as an agent need not be parasitic on another agent.

She seems to be suggesting that an evil person’s depending on a good trait somehow renders the evil person weak or unfit for life, so that we need merely invoke the sanction of the good or of victims to explain his successes, but that’s what I’d dispute. It’s not just that she doesn’t dwell on the latter case, but that she tends to conflate the two cases, invoking the first thesis to imply that evil is powerless, impotent, and easily vanquished, then glossing over the obvious fact that it isn’t.

LikeLike

“How does one lose track of a fact like that?”

Amphetamines?

LikeLiked by 1 person

LOL

LikeLike

Rand’s “wizened child” is also an odd inversion of the abused child on whose suffering all the world’s happiness depends, in Dostoyevsky and Le Guin.

LikeLike

I guess the two sets of images reflect our ambivalence toward abused children. On the one hand, abused children elicit sympathy as “pure” victims; on the other, child abuse is taken to explain psychological dysfunction in adulthood, and by implication to explain the sinister things adults manage to do.

LikeLike

Pingback: Randians vs. Stoics — Policy of Truth – carpediem

Still worth reading on this subject for the interesting mix of right- and wrongheaded thinking involved:

https://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Pajares/moral.html

A colleague of mine gave a convincing paper a few years ago arguing that for all that James got right in “Moral Equivalent of War,” the second half of the essay is little more than a counsel of despair. He made the point in part by by describing the psychological effects (on patients) of the widespread use of military metaphors in oncology (where patients are often described as “waging war” against cancer, or against particular tumors, conceived as alien invaders or occupiers). Not sure he ever published the paper, alas, but the point stayed with me.

LikeLike

I’ve seen this James piece cited (with what accuracy I don’t know) as the inspiration for such political phrases as “war on poverty,” “war on drugs,” etc.

LikeLike

Well, here is LBJ’s State of the Union address for 1964, where he coined the phrase “war on poverty.” It doesn’t mention James, but the rhetorical strategy sounds a hell of a lot like the one James was suggesting. Of course, it also sounds a hell of a lot like the strategy you would use to distract attention from the fact that you currently have 16,000 troops in Vietnam, want to send maybe a couple hundred thousand more, but would rather talk about something else.

https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/january-8-1964-state-union

LikeLike

You’re so cynical.

LikeLike

I think it was George Carlin who said that a cynic is just a disappointed idealist–in my case, a perpetually disappointed one.

LikeLike

Pingback: Stoicism and Free Will | Policy of Truth